|

A peer-reviewed

electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and ISSN

1541-0099 18(1)

– May 2008 |

Technology and Citizenry: A Model for Public

Consultation in Science Policy Formation

Gregory

Fowler

School of

Community Health

Portland State

University

and

Kirk

Allison

School of Public Health,

University of Minnesota

Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 18 Issue 1 – May

2008 – pgs 56-69

http://jetpress.org/v18/fowlerallison.htm

Abstract

Probably the most interesting feature of the 40-year history of biomedical

biotechnology is the extent to which it has been open to – and influenced by – concerns

over social values and the public’s voice. Good intentions notwithstanding,

however, benchmarks and best practices are woefully lacking for informing the

policy-making process with public values. This is particularly true in the

United States where the call for “public debate” is often heard but seldom

heeded by policy-making bodies.

Geneforum, an Oregon-based non-profit, has developed a practical

and working model designed to encourage deliberative democratic processes for

addressing the ethical and social issues raised by emerging biotechnologies.

Ordinary citizens do not need to be scientists to understand the important

implications of the new technological advances. When factual information and

basic principles are conveyed in linguistically and culturally appropriate

ways, the scene is set for a shift from monologue to dialogue, from

“I-thinking” to “We-thinking,” to occur.

This paper describes the Geneforum model structured to intensify

the democratization of policy decision-making, in general, using genomic

science, in particular, as one example of its application.

The calls for public

consultation

It was 40

years ago that the label, “genetic engineering” appeared in an essay entitled,

“Portents for a Genetic Engineering” (Hotchkiss 1965). Today, “functional

genomics” fuels new biomedical efforts of unprecedented scope and complexity

ranging from personalized genomic medicine (McGuire et al. 2007) and public

health genomics (Burke et al. 2006) to human enhancement. From the beginning of

the “new genetics,” biomedical biotechnology has been viewed by scientists as

involving social value commitments and thus requiring a more democratic

discussion. For example, Hotchkiss set the tone by concluding his essay with

the words:

The best

preparation will be an informed and forewarned public, and a thoughtful body

scientific. The teachers and the

science writers can perform their

historic duties by helping our public to recognize and evaluate these

possibilities and avoid their abuses. For these things surely are on the way.

(Hotchkiss 1965, 202.)

With the

advent of recombinant DNA techniques in the 1970s, the scientists themselves

were at the forefront of those who argued that: “[T]he social consequences of

the recombinant DNA technology are too enormous and important to be left to

specialists alone” (Nader 1986, 159).

Contemplating

the prospect of human applications of that technology in the 1980s, NIH developed

for human gene transfer research the most extensive public review process in

the history of biomedical experimentation, and in 1990, Nobel laureate James

Watson launched the U.S. Human Genome Project with a public commitment to

complement the molecular mapping of human chromosomes with research designed to

anticipate and address the social value issues raised by the project’s work:

Doing the

Genome Project in the real world means thinking about these outcomes from the

start, so that science and society can pull together to optimize the benefits

of this new knowledge to human welfare and opportunity. (Watson and Juengst

1992, xv-xvi.)

For many

scientists today, taking science and technology to the public is fast becoming

a recognized and valued activity. A recent full-page editorial in the journal Nature (2004) extolled the virtues of

“going public.” A year later, Alan Leshner, the Editor and CEO of the American

Association for the Advancement of Science, articulated a similar vision in an

editorial in Science about “where

science meets society” (Leshner 2005).

In the view

of Mark Cantley, former Advisor Research-Directorate-General of the European

Commission on Biotechnology,

Given

the profundity of the challenges thus brought into public and policy debates,

democratic theory in the era of the knowledge society must take on board the

involvement of citizens in the production, use and interpretation of knowledge

for public purposes. (Cantley 2005.)

In spite of

the many calls, a striking feature of the history of genetic engineering and

biomedical biotechnology, especially in the U.S., is the extent to which the

genome science policy process has remained largely impervious to the fears,

hopes and concerns of the public. As illustrated by the emotional and

persistent backlash against genetically modified organisms – and the more recent stem cell debates in the U.S. – strategies to integrate prevailing social values into the

science policy-making process remain controversial, at best, and inadequate in

the extreme. Unease is further complicated by

a regulatory divide between publicly and privately funded research, on the one

hand, and a deficit in clear articulation of fundamental concepts to the

public, on the other (Allison 2007).

As

a case in point, in March 2007 – acting on its mandate – the HHS Secretary’s

Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health and Society (SACGHS) solicited public

comments on its draft report of the promise,

opportunities and challenges of pharmacogenomics (SACGHS 2007). The committee received

58 comments: 53 from subject-matter experts, but only 5 from the public at

large. While many factors contribute to the disparity, at least one

which deserves serious attention is the suggestion that U.S. policy formation

regarding genome-based research and applications remains remote from the

public.

Notable

exceptions to this conclusion can be found primarily in Europe.

In a landmark

popular referendum in June 1998, Switzerland voted by a 2:1 majority not to ban

genetic engineering (Ribiero 1998). The popular initiative, called the “Gene

Protection Initiative,” was rooted primarily in a substantial degree of citizen

unease over what was initially viewed as a scary and mysterious new technology.

Its stated goals were the prohibition of transgenic animals, the banning of all

field releases of transgenic crops and the prevention of patenting certain

inventions of biotechnology. Before the popular vote took place, the Swiss

Parliament committed itself to enact a strict regulatory framework, but no bans.

In the intervening three years of intense public education by the media,

biotechnology industry, and the scientific and medical communities, general

opposition to genetic engineering decreased from 62 percent to 33 percent, and

acceptance increased from 25 percent to almost 40 percent.

These

significant shifts in public values reflect both a

proactive interest of the public, and a scientific community willing seriously

to listen, use understandable terminology, and actively engage in interviews

and forums (van Est and van Dyke 2000). Given time, money and the open sharing

of ideas, complex societal issues raised by new technologies can be brought to

the public’s attention allowing, at a minimum, for better-informed democratic

decisions to be reached.

In Denmark, The Danish Board of Technology, an arm

of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Development, recently celebrated two

decades of consensus conferences and scenario workshops with Danish citizens.

Working in collaboration with the Danish Parliament’s Committee of Science and

Technology, the focus of the two methods is to create a framework for dialogue

among policy-makers, experts, and ordinary citizens about technology policies

(Andersen and Jaeger 1999).

The United

Kingdom’s Wellcome Trust is the

largest non-governmental source of funds for biomedical research in the world (www.wellcome.ac.uk). Among its other

objectives, the Trust uses a broad spectrum of strategies to achieve its

commitment to the public engagement of science aimed at raising awareness and

understanding of the achievements, applications and implications of biomedical

research. The Trust’s “Public Perspectives on Human Cloning” was one of the

first publications to appear in the wake of the creation of “Dolly,” the

world’s first mammal cloned from an adult cell in 1998. Van Est and van Dyke (2000) view the English and Dutch

political responses to this event as making partial use of informed societal

debate, Switzerland and the Netherlands more fully so, while political systems

in the U.S., South Korea and Italy largely ignored its informative potential.

As further

confirmation that Europe is seriously committed to the pursuit of

public-interest science, in December 2001, the European Commission agreed to a

“Science and Society Action Plan.” The document sets out a new strategy to make

science more accessible to European citizens, and 38 objectives to achieve that

goal (see http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/action-plan/action-plan_en.html).

In

stark contrast to the above examples, the results of a research project

designed to assess the likelihood of implementing a Canadian model of public

consultation on xenotransplantation policy in the U.S, showed that the

regulation of American biotechnologies remains in the domain of the scientific

elite. In that study, consulted members

of the U.S. xenotransplantation community questioned the meaning of an

“informed public” and agreed that gathering public opinion is desirable but not

without rigorous public education strategies (Allspaw 2004). These observations

are similar to those articulated by the National Bioethics Advisory Committee

and numerous other blue ribbon federal commissions calling for “public debate”

and “a more educated public” in the policy-making process (see http://www.bioethics.gov/reports/reproductionandresponsibility/index.html).

While

“education” is clearly an important part of the equation, realizing social

responsibility in a democracy requires more than education alone. It requires

influence on the direction of policy decisions. It requires clear assertion of community values relevant to

policy options. It requires finding a way for ordinary citizens to work in

partnership with technical and scientific experts to produce policy that

expresses community values and uses the best facts available (Garland

1999).

As experience

with the Geneforum mode of public consultation demonstrates, complex societal

issues raised by a spectrum of emerging biotechnologies can be brought to the

public’s attention in ways in which informed democratic decisions about their

application can be reached. Ordinary citizens do not need to be scientists to

understand the important implications of the new technological advances. When

factual information and basic principles are conveyed in linguistically and culturally

appropriate ways, the scene is set for a shift from monologue to dialogue, from

“I-thinking” to “We-thinking,” to occur (Jasanoff 2005).

Part of that

transformation hinges on trust. Mistrust of the scientific establishment,

fueled in Europe by the infamous 1996 UK mad-cow disease fiasco, tells us that

attention must now be paid to the way in which knowledge and expertise is

expressed, heard and acted upon in dialogic encounters (Cunningham-Burley 2006)

and public engagement (Wynne 2006). Building trust is

bidirectional. Scientists often mistrust the public, viewing it as incapable of

coming to “right” conclusions regarding ends, prudential judgments regarding

means, or regarding limits which are necessarily a function of values

intersecting resource constraints and (perceived) risk (Taylor 2007). “Deciding what is important requires value judgments.

Deciding how to achieve a higher level objective requires factual knowledge”

(Keeney 1992).

This raises the issue of spheres of competency. Expert technical

knowledge is critical for designing the means to achieve the valued outcome.

So, how do we

develop public trust in the practice and application of the newly emerging

biotechnologies, and the democratic institutions which support them, in the

twenty-first century, and beyond? Can we give new life to the concept of

democracy – of government by the people – by weaving ordinary citizens more

deeply into our decision-making processes; and through those

processes, build community?

Cunningham-Burley

(2006) suggests “… a sharing of power and greater public involvement in the

early stages of policy formation and scientific and medical agenda setting,” echoed by Joley and Rip

(2007) specifically in the case of contentious research and development.

Sheila Jasanoff

(1995) reminds us of the need to talk, and sometimes to argue, about the

scientific and technological choices that confront us: “In science, as in

politics, the need for this process of inquiry, debate and learning – ‘participatory democracy’ – is endless.”

According

to Beierle (1999), five social goals are key to evaluating public consultation

approaches:

1. Educating and informing the public;

2. Incorporating public values into

decision-making;

3. Improving the substantive quality of decisions;

4. Increasing trust in institutions; and

5. Reducing conflict and building community

Communication, listening, and transparency are mutually

reinforcing requisites for realizing these goals. While there

is obviously no one single formula for success in all of these arenas, one

model developed in Oregon to promote dialogue at the intersection of genetics,

ethics, and public values – an extension, actually, of the Oregon Health

Decisions Model (Garland 1994, 1999) – comes

close: Geneforum (http://www.geneforum.org).

A rational model for

public consultation

Since its

birth in 1999, Geneforum has evolved into an on- and off-line information

platform for collecting public values and disseminating objective information

on genome science to a broad spectrum of stakeholders.

Geneforum

endeavors to create, in the words of Hotchkiss, an “informed and forewarned

public” by addressing issues that are, for the most part, in the early stages

of development and, in many cases, lacking any federalized policy framework

(e.g., genetic privacy, gene doping, direct-to-consumer marketing of DNA

information).

Geneforum

believes that this “ahead-of-the-curve” approach is critical toward directing

genome science in socially-responsible directions, a strategy which is

significantly different from those generally used in the U.S. that allow the

science to proceed until it reaches a critical impasse before engaging in any

public discourse.

Driven by its

core belief that public policy decisions will result in better outcomes to the

extent that they are based on both public values and scientific knowledge,

Geneforum uses a three-pronged approach designed to optimize the creation of

socially responsible genetic science policy:

1.

Increase the capacity of citizens to understand the impact of genetic science

in their lives (Education);

2. Enable citizens to better understand and

make informed decisions about the complex social and ethical dimensions of

genetic research through dialogue (Engagement); and

3. Informing genetic policy through the

measurement and monitoring of public values (Consultation).

Together,

these approaches deliver what we label as “democratization,” an effort to

inform the public consciousness – without manipulating it – and, in so doing,

to build the capacity for bringing an informed public voice into the genetic

policy process.

The Geneforum process

As

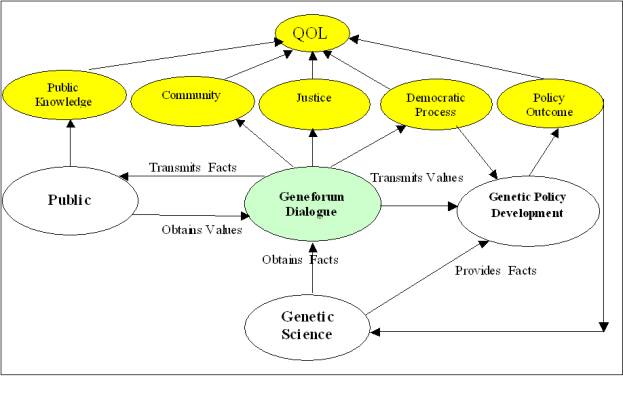

illustrated in the flow schematic in Diagram 1, Geneforum relies upon genetic

science for scientific facts and issues and then creates on- and off-line

dialogues between the public and experts. The process

strengthens important elements of democratic society: community, justice, and

democratic processes. The ‘products’ of the process are an increase in public

knowledge and, ultimately, policy outcomes. Public knowledge is mediated

through public accessibility of content (hence a technical article in a journal

does not automatically qualify as public knowledge in this sense, even if

produced via public funding in a public institution). Democratic processes,

public values and scientific data inform genetic policy development, whose

policies feed back into genetic science as

policy: the social accountability of science to public values. Public

knowledge, community, justice, democratic processes and policy outcomes support

quality of life in a democracy.

Diagram 1: An Overview of the Geneforum Process

As an outcome

of this multi-faceted process, citizens become more capable of discussing and

understanding the science of genetic research – and the complex social and

ethical issues generated by it – and strengthen

democratic deliberation in policy development.

As depicted

in Figure 1 below, the Geneforum process also consciously creates an environment

of dialogue and community building within the public sphere on- and off-line

(e.g., at its Web site and through focus groups and random sample surveys).

Figure 1:

Geneforum Strategies for Promoting Dialogue and Building Community

|

Geneforum

Offline Activities Community talks Public forums Focus groups Public opinion surveys Programs with schools and educational

institutions Media outreach |

Geneforum

Online Activities Online surveys and polls Online forums Consumer resource guides “Genetizen” blog authored by experts Interviews with thought leaders User participation tools (e.g., posting of

comments and questions) Knowledge warehouse for offline activities

(e.g., past public forums, survey summaries and analyses) |

Through its

consultative process, Geneforum obtains values from the public (hopes, fears, priorities and

uncertainties about the issue or issues being explored) which it transmits to

the genetic policy development process wherever it is being debated, from

corporate boardroom to legislative chambers. As a result, public participation

in a deliberative (discursive) democracy is encouraged, and socially just

policy outcomes are made more likely.

Geneforum

acts on the belief that public policies are ethically justified and legitimate

to the extent that they emerge from the reasonable deliberation of free and

equal citizens who will be significantly affected by them (i.e., a good process is the best route to good policy

outcomes). Of note, deliberative processes support

three important goals: fulfilling the normative rationale of democracy in

policy formation, augmenting the legitimacy of policy formation and

implementation, and finally contributing to professional enquiry, including in

the area of genomics enhancing population participation upon which that

knowledge base depends (Fischer 2007).

While

Geneforum advocates passionately on behalf of good process, it never lobbies,

or intentionally

introduces bias on behalf of particular policy alternatives. Impartiality is a

guiding principle of the Geneforum model.

Linking the public voice

with the policy process

In

order to develop a genetic policy which reflects informed public values,

Geneforum uses several unique strategies:

1. Identification of a policy receptor site;

2. Translation of public values into

policy-relevant input;

3. Partnership with experts; and

4. Separation of fact (technical content) and

value.

Receptor site

Policy

receptor sites are vehicles of policy which, in order to focus their

activities, connect the public to the actions of the state through identifiable

social structures such as committees, commissions, legislatures, boards of

directors, and negotiation teams (Garland 1999).

In the Oregon

State Legislature, the “Advisory Committee on Genetic Privacy and Research” is

one such entity. Working on behalf of the members of that committee, Geneforum

continues to use its tools of consultative strategies to “… educate the public

and obtain public input on the scientific, legal, and ethical development in

the fields of genetic privacy and research” (Fowler 2002).

The focus of

generating public input is to tap into values by way of value-laden questions

that can be effectively and wisely discussed

among a broad cross section of the public. For example, who owns genetic information?

Is it the individual? The family? Humanity? Who should have access to genetic

information? Private individuals or families? Businesses? The State? These are

not factual matters to be decided by experts, but rather

a matter of the values of the community (Fowler and Garland 1999; Garland 1999).

Partnership with the

experts

Going to the

community for its values won’t work if there is no partnership with experts.

The collaboration makes most sense when it is seen as half of a joint effort

between the general public and technical experts, both helping to shape the

political decisions of policy makers. The expertise Geneforum seeks comes from

a broad spectrum of sources – whatever areas

necessary in order to move the policy process forward.

The values that guide public policy decision-making should

be rooted in the values of the public, and the beliefs that guide public policy

decision-making should be based on scientific findings. This requires that the

public, as stakeholders, evaluate relative desirability while experts evaluate

relative likelihood (Anderson et. al. 1998).

A model of public consultation structured to partner citizens,

experts, and policy makers in a coordinated process can “broadly formulate the

decision problem, guide analysis to improve participants’ understanding of

decisions, seek the meaning of analytic findings and uncertainties, and improve

the ability of interested and affected parties to participate effectively in

the risk decision process” (Stern and Fineberg, 1996: 3).

Fact-value separation

Normatively,

decision-making consists of two phases: problem structuring and evaluation (Von

Winterfeldt and Edwards 1986; Clemen 1991). Problem structuring involves the

identification of alternatives, values that distinguish the alternatives from

one another, and uncertain events that could affect the values associated with

a particular alternative.

Evaluation is

a matter of weighing the relative desirability of various outcomes and the

likely impacts of various uncertain events in deciding which alternative is, on

balance, preferable.

The Geneforum

methodology of fact-value separation, that is

distinguishing technical from value judgments, is predicated on the

belief that a clear understanding of this distinction can enhance the quality

of public input to public policy decision-making and counter the objections

that are so frequently raised when public input is offered to inform public

policy decision-making.

As described

in Table 1, the process involves three-steps:

Table 1: The Geneforum Fact-Value Separation Process

|

Values: Relative importance |

Get from the public |

|

Facts: Relative likelihood |

Get from experts |

|

Alternatives: Relative preference |

Get from decision makers |

The

final step of trading off information about facts and values to determine the

relative desirability of various public policy alternatives is left to the

policy decision makers.

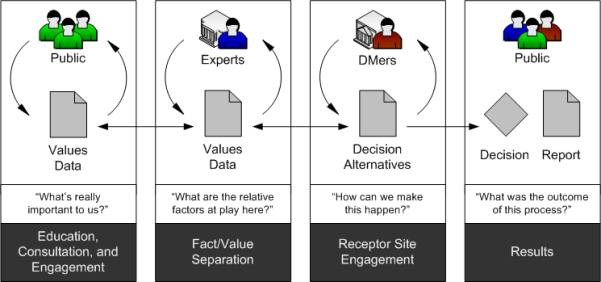

As

depicted in Figure 2, the Geneforum consultation process can be summarized into

three steps:

1. Experts review the initial compilation of

public values to look for factual assumptions that may be questionable (i.e.,

the probability of policy X resulting in consequence Y) and, when possible,

provide their best judgments as to the correct assumption(s);

2. Policy makers then review the draft to see

how it can be made more useful for guiding choices among the alternatives with

which they will be faced;

3. The public participants (with facilitation) create a final report to be sent to the policy

making receptor site.

Figure 2: Technology and

Citizenry Model v.1.0

The outcome

of this process will be, at the very least, a structured list of shared values

and a list of important value differences.

It may also be possible to provide a list of differing beliefs regarding

matters of technical judgment that account for differences in preferences among

alternatives and also a list of possible modifications to current plans that

can be expected to enhance public support.

The Geneforum proof-of-concept

The 1999

Oregon Legislature created the Genetics Research Advisory Committee (GRAC), a

gubernatorially mandated group of Oregon healthcare professionals and

policymakers, to explore the issues of genetic privacy and research in Oregon.

Throughout its deliberations, the GRAC had the benefit of input from Oregonians

around the state generated from a series of focus groups, statewide surveys,

interviews with opinion leaders, town hall meetings, public forums, and

responses to internet interactive scenarios, all developed and conducted by Geneforum.

As a result of the data contributed by these consultative public strategies,

the GRAC included in its final report to the state legislature a unanimous

recommendation to create a new, and ongoing, advisory committee to monitor

genetic research and privacy throughout the state. The following language in

that Bill reflected both the experienced – and proposed – role of the public in

that process:

As

part of its regular activities, the Advisory Committee on Genetic Privacy and

Research shall create opportunities for public education on the scientific,

legal, and ethical development within the fields of genetic privacy and

research. The committee shall also elicit public input on these matters. The

committee’s recommendations shall take into consideration public concerns and

values related to these matters. The committee should make reasonable efforts

to insure that this public input is representative of the diversity of opinion

in the Oregon population. (ORS 192.549(8);

Fowler 2002.)

In the

intervening six years, Geneforum has remained a member – and continues to work

on behalf – of the ACGPR. Many of the findings generated by Geneforum’s ongoing

work have enriched, and extended, the committee’s deliberations, and several

have been responsible for keeping Oregon’s genetic privacy legislation one of

the most comprehensive and forward-looking documents in the U.S.

Conclusion

The Geneforum

model presented here provokes some points to consider for the future of

emerging technologies, in general, and the science of emerging technologies

like genetic enhancement, in particular.

American

scientists and science policy makers need to recognize that the public is a key

part of the thinking society, with particular interests, concerns and questions

about science and technological innovations and how these will shape the future

of life on this planet. The public at large is also

somewhat less subject to the effects of intramural disciplinary competition.

Increasingly, science and technology intersect with people’s beliefs and

values, in large part because science and technology are becoming involved in

issues with ethical and value dimensions regarding the substantive nature of

human being on the one hand and the limits of instrumentalization on the other.

To address

the newly invested public of science, the idea

of a one-directional flow of information needs to be replaced by dialogue,

engagement and participation. That means questioning some of the bland and

often pejorative stereotypes of the public, finding out more about the public

and developing ways of talking with and to them more effectively.

That must

have been in Ian Wilmut’s mind when he introduced “Dolly,” the world’s first

mammal created from adult cells, to an august audience of scientists,

philosophers, religious leaders and the media at a 1997 AAAS Symposium, with

the words,

I

believe that it is important that society decides how we want to use this

technology and makes sure it prohibits what it wants to prohibit. (Wilmut

1997.)

For that to

happen, however, effective community engagement will be required and that can occur only if governance 1) ensures that the

engagement is reflective of the community – that the aspirations of the special

interest groups are calibrated against a broad cross-section of the community;

2) is open with the process of engagement and with sharing information, and with

broadly-based steering or reference groups to guarantee transparency; 3) and

all stakeholders listen genuinely and empathetically to all voices, and be

genuinely committed to embracing the outcomes.

Only in these

ways can better decisions, more trust, stronger communities, and embodied

democracy be attained.

Scientists,

policy-makers and industry also need to collaborate closely and acknowledge the

obligation they have individually to engage in dialogue with different groups

of the public in accessible but accurate language.

This engagement needs to be in clear, non-technical terms, including benefits

and costs, and addressed to discrete citizen concerns. While public perceptions

and beliefs that run counter to de facto

expert knowledge are not acceptable justifications for public policies (Brunk

2006), the public is capable of differentiating issues, even if they do not

understand all technical details:

People may not possess “expert knowledge,” but this does not mean

they have nothing to contribute to decisions about science and technology.

(Jasanoff 2005)

The

lack of scientific knowledge among the general public often leads policy makers

to rely solely upon expert input and omit or trivialize the ordinary citizen’s

role in policy development (Brunk 2006; Dean 2005). On the other hand, such an

approach can exacerbate public policy conflicts (Sarewitz 2004).

We live with

the benefits and the curses of technology, often working to remedy past

mistakes through further advances. This ongoing process of inflicting damage

and then playing “catch up” increasingly threatens the biogeochemical web upon

which all of humanity depends. Until now our technology has been focused on

shaping our world. But even through all of that,

as a biological organism, the essence of our humanity has not been altered

significantly.

For the first

time, the biological determinants of humanity are becoming subject to technological

manipulation. What does the concept of progress, or enhancement, mean when

applied to the human genome? Do we have the necessary expertise on values

consensus to proceed? Are we prepared to live with the unintended consequences?

The genomics

revolution rolls on, promising tremendous improvements in our ability to secure

a new level of physical well being while simultaneously making us very uneasy

about the future. So, the question then becomes: If we can’t stop the process,

how do we guide it?

Too often the

pluralism of our society is seen as an obstacle to creating a viable ethical

and political consensus on science and technology. Taken as a whole, the basic

objective of the Geneforum model – and others which seek to address similar

challenges in different ways – is to make that pluralism a source of

enlightenment rather than confusion, an enabling rather than a disabling

feature of our democratic way of life.

References

Allison,

K.C. 2007. Diogenes’ lamp: Performatives, stem cell politics, and the public

representation of science. American

Public Health Association 135th Annual Meeting and Exposition.

Washington, DC. November 7, 2007.

Allspaw, K.M.

2004. Engaging the public in the regulation of xenotransplantation: would the

Canadian model of public consultation be effective in the U.S.? Public Understanding of Science 13

(2004): 417-28.

Andersen,

I-E. and B. Jaeger. 1999. Scenario workshops and consensus conferences: Towards

more democratic decision-making. Science

and Public Policy 26(5): 331-40.

Anderson. B.,

M. Garland, and H.D. Jones. 1998. Consumers want choice and voice. In Grading Health Care: The science and art of developing consumer

scorecards, ed. P.P. Hanes and M.R. Greenlick. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

49-68.

Beierle, T.C.

1999. Using social goals to evaluate participation in environmental decisions. Policy Studies Review 16: 75-103.

Brunk,

C.G. 2006. Public knowledge, public trust: Understanding the knowledge deficit.

Community Genetics 9: 178-84.

Burke W.,

M.J. Khoury, A. Stewart, and R.L.Zimmern.

2006. The path from genome-based

research to population health: Development of an international public health

genomics network. Genet Med., 8:

451-58.

Cantley, M.

2005. In our own hands. Nature 437:193.

Clemen, R.T.

1991. Making hard decisions: an

introduction to decision analysis. Boston: PWS-Kent.

Cunningham-Burley,

S. 2006. Public knowledge and public trust. Community

Genetics 9: 204-210.

Dean,

C. 2005. Scientific savvy? In the U.S., not much. New York Times, August 30, 2005. [Interview with J. Miller.]

Editorial

2004. Going public. Nature 431: 883.

Fischer,

F. 2000. Citizens, experts, and the

environment: The politics of local knowledge. Durham and London: Duke

University Press, 2000: Part 1, 2.

Fowler, G.

2002. Linking the public voice with the genetic policy process: A case study. Oregon’s Future 3(2) Fall 2006: 28-32.

Fowler, G.

and M. Garland. 1999. Translating the human genome project into social policy:

A model for participatory democracy. In

Genes and morality: New essays, ed. V. Launis, J. Pietarinen, and J.

Raikka. Amsterdam and Atlanta, GA: Rodopi Press: 175-93.

Garland,

M. 1994. Oregon’s contribution to defining adequate health care. In Health Care Reform: A Human Rights Approach,

ed. A.R. Chapman. Washington, DC:

Georgetown University Press. 211-32.

Garland, M.

1999. Experts and the public: A needed partnership for genetic policy. Public Understanding of Science 8:

241-54.

Hotchkiss,

R.D. 1965. Portents for a genetic engineering. Journal of Heredity 56(5): 197-202.

Jasanoff,

S. 2005. Designs on nature: Science and

democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton

University Press.

Joley,

P-B. and A. Rip. 2007. A timely harvest. Nature

450: 174.

Keeney,

R.L. 1992. Value-focused thinking: A path

to creative decisionmaking. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Leshner,

A.I. 2005. Where science meets society.

Science 307: 815.

McGuire, A.

Cho., M.K., McGuire, SE & Caulfield, T. 2007. The future of personal genomics. Science 317: 1687.

Nader, C.

1986. Technology and democratic control: The case of recombinant DNA. In The gene splicing wars: Reflections on the

recombinant DNA controversy, eds. R. Zlinskas and B. Zimmerman. New York:

Macmillan: 139-67.

Oregon Revised Statutes 192.549.

Advisory Committee on genetic Privacy and Research. [2001 c.588 §7; 2003 c.333

§6]

Ribiero, C.

1998. Keeping the public informed about science: Lessons from the Swiss gene

protection initiative. Molecular Medicine

Today 4: 14.

Sarewitz

D. 2004. How science makes

environmental controversies worse. Environmental

Science and Policy 7: 385-403.

Secretary's Advisory Committee on Genetics,

Health, and Society. 2007. [Request for public comment on draft report Realizing the Promise of Pharmacogenomics: Opportunities

and Challenges (2007).] Federal Register (March 28, 2007)

72(59): 14577-14578. (http://a257.g.akamaitech.net/7/257/2422/01jan20071800/edocket.access.gpo.gov/2007/07-1532.htm.)

Stern P.C. and Fineberg H.V., eds. 1996. Understanding risk: Informing

decisions in a democratic society. Committee on Risk

Characterization. Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education.

National Resource Council.

Taylor,

PL. 2007. Rules of engagement. Nature 450: 163-64.

van Est, R. and van Dyke, G. 2000. The public

debate concerning cloning. International experiences. TA-Datenbank-Nachrichten 9(1): 109-115.

(http://www.itas.fzk.de/deu/tadn/tadn001/tagungsbericht1.htm.)

Von

Winterfeldt, D. and W. Edwards. 1986. Design

analysis and behavioral research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Watson, J.,

and E. Juengst. 1992. Doing science in the real world: The role of ethics, law

and the social sciences in the human genome project. In Gene mapping: Using law and ethics as guides, eds. G. Annas and

S. Elias. New York: Oxford University Press: xv-xix.

Wilmut, I.

1997. Quoted in G. Kolata, Scientist Reports First Cloning Ever of Adult

Mammal. New York Times, February 23,

1997.

Wynne, B.

2006. Public engagement as a means of restoring public trust in science –

Hitting the notes, but missing the music? Community

Genetics 9: 211-20.