The

Japanese Roboticist Masahiro Mori’s Buddhist Inspired Concept of “The Uncanny Valley” (Bukimi no Tani

Genshō, 不気味の谷現象) W.A.

Borody Department of Political Science, Philosophy and

Economics Nipissing University, Canada Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 23 Issue 1 – December 2013 - pgs 31-44

ABSTRACT In 1970, the Japanese roboticist and practicing

Buddhist Masahiro Mori wrote a short essay entitled “On the Uncanny Valley” for

the journal Energy (Enerugi, 7/4, 33–35). Since the publication of this two-page

essay, Mori’s concept of the Uncanny Valley has become part and parcel of the

discourse within the fields of humanoid robotics engineering, the film

industry, culture studies, and philosophy, most notably the philosophy of transhumanism.

In this paper, the concept of the Uncanny Valley is discussed in terms of the

contemporary Japanese cultural milieu relating to humanoid robot technology,

and the on-going roboticization of human culture. For Masahiro Mori, who is

also the author of The Buddha in the

Robot (1981), the same compassion that we ought to offer to all living

beings, and Being itself, we ought to offer to humanoid robots, which are also

dimensions of the Buddha-nature of Compassion. “What is this, Channa?” asked

Siddhartha. “Why does that man lie there so still, allowing these people to

burn him up? It's as if he does not know anything.” “He is dead," replied

Channa. “Dead! Channa, does everyone

die?” “Yes, my dear prince, all

living things must die some day. No one can stop death from coming,” replied

Channa. The prince was so shocked he

did not say anything more. (The

Fear and Terror Sutra (Bhaya-bherava

Sutta) translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu) Masahiro Mori and The

Cultural Dimension of Japanese Robotics In a New York Times article published in

1982, entitled “Japan’s Love Affair with the Robot,” Henry Scott Stokes discusses

some stark contrasts between the degree to which the robotic industry was

developed in Japan in the early 1980s, as opposed to most other countries.

Stokes focuses on the degree to which the Japanese attitude toward the robot radically

differed from the common Western attitude. For example, while “the modern robot

industry had its start in the United States,” Stoke states, “there are 140

robot manufacturers in Japan as compared with 20 in the United States” (Stokes

1982, 24). And as for different

attitudes towards robots, Stokes describes how new industrial robots in Japan were

more often than not first blessed by Shinto priests, after which the employees

burst into applause, welcoming “the new member” of their team.1 Typically,

Stokes says, workers greet the robots at the start of the working day with “Ohayo gozaimasu,” Good Morning! A recent

documentary, Japan: Robot Nation

(2008) depicts the almost seamless relationship between the Japanese and their robot

culture. Jennifer Robertson, a specialist in Japanese robotics, discusses the massive

demographic shift in an aging population in Japan; as a result, she says, Japan

is embracing the idea of a form of multiculturalism that factors in the “social

robot” as an intrinsic aspect of day-to-day life, including robots that can

help bring up the kids, teach, take care of the elderly, and even grocery shop

(Robertson 2010). According to professor Ono Goro of Saitama University in his

popular book Accepting Foreign Workers

Spoils Japan (2008), the Japanese would, in general, prefer a humanoid

robot in their social milieu rather than a human foreigner (Japan: Robot Nation

2008). Professor Goro and many other nationalists of his ilk argue that robots

are better for Japan than immigrants when it comes to solving the evolving demographic

decline in the population. Japan presently has the highest number of industrial

robots per capita in the world and has formally articulated the roboticization

of its culture as a way of maintaining its economic prestige: the government-sanctioned

Innovation 25 Vision Statement of

2007 contains an official plan to implement personal humanoid robots in every

home and school environment by the year 2025 (Government of Japan 2007). There are

differing explanations to account for the uniqueness

of the modern Japanese acceptance of robots and robot culture. Some point to

the Japanese tradition of the imaginative culture of human/nonhuman crossovers in anime, manga and Karakuri Ningyo2

puppet culture, others to what they view as the ritualistic, formalistic, i.e.,

“robotic-like” aspect of traditional Japanese culture. Still others refer to

the legacy of the so-called “Eastern/Asian/Oriental”

embrace of the “Oneness of all things,”

even when it comes to the dichotomy between virtuality/reality. This particular

embrace of Oneness is then opposed to the so-called “Western,” Judeo-Christian Genesis version of humans as separate

from, but ruling over, the rest of creation. Osamu Tezuka (1928–1989), who is considered

the central figure in the development of both anime and manga in Japan after

World War II, expresses this sentiment: Unlike Christian Occidentals, the Japanese don’t make

a distinction between man, the superior creature, and the world about him.

Everything is fused together, and we accept robots easily along with the wide

world about us, the insects, the rocks – it’s all one. We have none of the doubting

attitude toward robots, as pseudohumans, that you find in the West. So here you

find no resistance, just simple quiet acceptance. (Stokes 1982, 6) While this

explanation is convincing on a surface level, it does not mesh with Japan’s

pre-1945 use of technology as an extension of the domination of the sword, as

in the bushido ethic of the samurai,

as Japan’s techno-military prowess demonstrated pre-1945.3 Although

the militarists of the period viewed technological mechanization in a utopian

manner, a wide-spread skepticism of such mechanization pervaded Japanese

society. For example, much pre-War Japanese literature, was concerned with what

Miri Nakamura he has termed the Mechanical

Uncanny: “the literary mode that blurs the line between what is perceived

as natural and what is perceived as artificial” (Nakamura 2002, 365). This Mechanical Uncanny, states Nakamura, led

Japanese intellectuals to bring out the “terror” that can be brought about through

technological mechanization. According to Nakamura, much prewar Japanese

literature attempted to “destabilize” the place of technology in society, in an

attempt to subvert “the ideologies of the machine age”: Machines and technology in prewar Japan, however, did

not simply represent social progress; they also came to be associated with fear

and degeneration. In the words of one scholar, prewar literature depicting

machines was in “a constant flux between a utopian dream of machines on the one

hand and a pessimistic nightmare of them on the other.” (Nakamura 2002, 366):4 The end of WW

II marks a major shift in Japan’s technological development: what can be

described as a shift from the belligerent to the benign. Japan’s present

political constitution was imposed by the Allies following World War II and was

intended to replace Japan’s prewar militaristic and absolute monarchy system. Chapter

Two, Article 9 of Japan’s present constitution (which came into effect in

1947), entitled “The Renunciation of War,” enforces pacifist social values, and

hence, by implication, pacifist technology: Aspiring sincerely to an international peace

based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a

sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of

settling international disputes. To accomplish the aim of the preceding

paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will

never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized. (Constitution of Japan 1947) If the Axis

powers had been victorious at the conclusion of WWII, it might have been the

Americans and Soviets who would have been forced to develop more peaceful uses for

robotic technology. As it happened, in both the Soviet Union and the United

States, post-1945, economically belligerent, i.e., military reasons, provided a

driving force in the interest in robotics and technology. By contrast, Japan,

given Article 9 of its constitution, has mainly been motivated by economically peaceful

reasons – an

impulse to make life less menial while at the same time more profitable and pleasurable.

It is in this context that the Buddhist roboticist Masahiro Mori (born 1927) is

such a significant figure in the Japanese robotics and AI community. Mori’s pacifist

approach to technology and robotics best represents the postwar Japanese

thinking about the role of robotic technology in modern society.5 Masahiro Mori: The Uncanny

Valley Although Masahiro

Mori is most well known outside of Japan for his development of the concept of

the Uncanny Valley, he is more importantly recognized in Japan as the founder

of the Jizai Kenkyujo (Mukta Institute, 1970), an influential Buddhist-based,

Japanese think-tank providing corporations and research centres with assistance

regarding roboticization and automation. In this capacity, he has had a direct

influence on the development of some of the more advanced humanoid robots to

have been developed in Japan, such as, for example, Honda’s humanoid robot Asimo.6 He is the author of The Buddha in the Robot: A Robot Engineer’s

Thoughts on Science and Religion (1974). He is also the founder of Robocon,

a world-wide amateur robot contest intended to share and celebrate robot

engineering technology. Formerly an engineering and robotics professor at the Tokyo

Institute of Technology, Masahiro Mori is at present (2013) the Emeritus

President of the Robotics Society of

Japan. In his 1970,

two-page, koan-like article entitled “The Uncanny Valley,” Mori argues that the

more social robots (as opposed to

industrial robots) are designed to appear 100 per cent humanlike, the more they

will appear less human, strange, unlikeable and in some cases horrific, resulting

from some technological glitch in either their appearance or movement, thus

causing a fearful sense of the “uncanny,”

in the way a corpse, or worse yet, a zombie causes a sense of uncanny

strangeness or emotional recoiling. In a peaceful society – a more Article 9

society, and for Mori a more Buddhist-based society – robots and robotically enhanced humans ought

to be experienced as non-threatening. In 1970, on the basis of his concept of

the Uncanny Valley, Masahiro Mori advised his fellow roboticists to design

humanoid robots that act and perform as humans, but do not look and move

exactly like the human, in order that the humanoid robots will be more socially

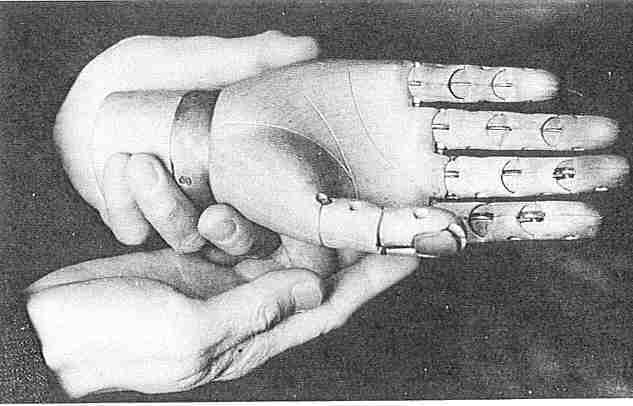

accepted. Mori based his idea

of the Uncanny Valley on a personal experience: as a roboticist who developed

the engineering for robotic/prosthetic fingers, he felt that even the most

humanlike prosthetic hand available commercially in 1970, which had been

developed in Vienna, still left one with a sense of the uncanny and unfamiliar.

Despite how technologically developed this prosthetic hand was, and how

humanlike it appeared, shaking such a cold, lifeless hand, says Mori, left one

shocked, and horrified to a degree. Hence, in the case of a siliconed humanlike

prosthetic hand, Mori suggests that a wooden hand, modeled on a version of the

hand of the Buddha of Compassion (Mori 2012, 100),7 but with the

same technological precision of the Viennese hand, might more likely be accepted

by the human, with a sense of familiarity rather than aversion. The core of

Being, from a Buddhist perspective, is compassion. Why create new forms of

being that are intrinsically forms of aversion rather than compassion? This is

the Buddhist subtext of Mori’s concept of the Uncanny Valley. Mori begins his

paper with a graph based on the mathematical function y = f(x), an abstract

formula that explains simple cause and effect: the value of y depends on (or is

an effect of) the value of x. For example, stepping on the gas pedal (x)

results in causing the car (y) to move. Normally, this cause-effect

relationship holds in our world. But not all things, Mori observes, fall under

the formula y = f(x). Simple cause and effect is not the way the world works. Although

in our everyday, practical world, y = f(x) is the way things often work, it is not always so: This kind of relation is ubiquitous and easily

understood. In fact, because such monotonically increasing functions cover most

phenomena of everyday life, people may fall under the illusion that they

represent all relations. Also attesting to this false impression is the fact

that many people struggle through life by persistently pushing without

understanding the effectiveness of pulling back. That is why people usually are

puzzled when faced with some phenomenon that this function cannot represent. (Mori

2012, 98) Mori’s own

example is taken from the movement of walking: in climbing a mountain, there

are hills and valleys, with no necessary y = f(x) cause and effect relationship

for getting from point A to B. In the attempt to create 100 per cent humanlike

resemblance in robotic technology, we humans fail. Stuffed animals and puppets

are more accepted by us as fellow travellers than such things as prosthetic

hands that are created to appear 100

per cent humanlike. Such human creations end up in the Uncanny Valley,

alongside the experience of human corpses

and zombies:

(Mori

2012, 99) Mori developed

his concept of the Uncanny Valley after attending Japan’s space-age themed

Expo’ 70 held in Osaka in 1970. Expo ’70 was held at the height of the Cold

War, which was, in a political chessboard of real-time contestation, played out

in the jungle-environment of the Vietnam War, a brutal display of human

ideological violence that claimed the lives of approximately two million

Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians, and 60,000 Americans. In the context of

this Cold War mentality, Expo ’70 had as its “alternative” theme the “Progress

and Harmony for Mankind,” à la

Article 9 of the Japanese constitution. This Expo

carried on the tradition of the first international Expo, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of

all Nations, held in London in 1851. The ultra-modern architecture of the

buildings of Japan’s Expo ’70 rivalled in both ingenuity and uniqueness

London’s Crystal Palace. On display

in this Expo were a large moon rock brought back by the Apollo 12 astronauts in

1969; the first IMAX film; the first spherical concert hall; recently developed

mobile phones based on local area networking; the most advanced magnetic

levitation train technology; and a wide variety of prosthetic devices and humanoid

robots. In the after-effects of this exuberantly utopian celebration of the

infinite moral and technological perfectibility of the human being, Masahiro

Mori tossed in a monkey wrench with his two-page publication of “The Uncanny

Valley.” In one off-handed comment Mori states that “creating an artificial

human is itself one of the objectives of robotics” (Mori 2012, 98) (such a

statement would horrify the likes of a Heidegger, Fukuyama or Margaret

Atwood). However, his concept of the Uncanny Valley was a symbolic

counter-thought to some of the more utopian ideals of Expo ’70. It questioned,

however obliquely, the concept of the utopian desire to remanufacture the present human, ad infinitum, but with better technology. While the

concept of the Uncanny Valley has since played a significant role in the

Japanese robotics industry devoted to the development of social robots, it has recently

garnered more interest in the film industry, especially the American film

industry. CGI technology has allowed for more of a cross-over between animation

and realism. However, if an animated character appears too almost-real, such as Tom Hanks in the movie Polar Express (2004), the audience recoils. Animation is not yet at

the point that it can replicate realistically a virtualized human. Hence, because

it fell into what Mori would describe as the Uncanny Valley, Polar Express was a box-office flop,

while the movie Avatar (2009), which

did not depend on complete animated human likeness, was a success (although it

was a poor movie for other reasons relating to its maudlin plot). It is also

clear that the “face” or “avatar” of the IBM supercomputer Watson was developed

with a concept of the Uncanny Valley in mind, when it first appeared in the

quiz show Jeopardy! in February of

2010, in a human-versus-machine contest (Watson came in first place). As Watson had

to appear beside two humans, its “appearance” and “movement” were of critical

importance for its designers. David Ferrucci, Watson Principal Investigator of

IBM Research, describes the approach that was taken in this project to present

a “face” or “avatar” for Watson, which is simply a cluster of ninety IBM Power

750 servers: Lots of thinking went into this. Should it be

humanoid, should it be abstract? In the end, what really made a lot of sense

was to be really clear that this is an IBM creation and what better than “the

smarter planet” logo for communicating that? (Davis 2011)8 The “smarter

planet” logo (Mori’s “still”) was coupled with forty-two coloured threads criss-crossing

the globe (Mori’s “movement”). Although Watson’s engineers gendered it as male

(given its male name and voice), they did not attempt to enter the Uncanny

Valley by associating an exact human-like face or avatar to it. Interestingly,

this idea appears to dominate more recent developments in prosthetics, as is

evidenced by DARPA’s recent mind-controlled, bionic arm-and-hand, which can be

used either with a silicon covering, or without one (UltraTechTalk, 2012), and

Aimee Mullins’ demonstration of her twelve different types of prosthetic legs,

some of which look human-like, and some which do not (Mullins, 2009). In a

recent study carried out at Princeton University, even monkeys appear to have the

sense of an Uncanny Valley when confronted with images of monkeys’ faces that

appear almost close-to-real. Instead

of cooing and smacking their lips when viewing exact representations of other

monkeys, the monkeys almost immediately avert their glances and act frightened

when confronted by the almost close-to-real

images (MacPherson 2009). On the other

hand, while there are roboticists who have heeded Mori’s advice, and created

human-like, social robots that appear more anime-like,

others have attempted to create social robots that are intended to replicate an

exact, 100 per cent human likeness, and there are some who argue that, when it

comes to Robotics and Artificial Intelligence, the sense of the so-called Uncanny

Valley soon fades, as it would fade, for example, with more exposure to a

prosthetic hand, such as the Viennese hand. In fact, within minutes, some

roboticists claim, even if a very humanlike robot appears uncanny, the sense of

the uncanny dissolves quickly (Sofge 2010, 2): David Hanson, a roboticist whose company, Hanson

Robotics, specializes in ultra-realistic robotic heads ,

actively seeks out the uncanny. He keeps the motors in his rubber-skinned faces

noisy and overtly robotic, and sometimes presents these lifelike talking heads

mounted on a stick. And for better or worse, even the shock value of Hanson’s

buzzing, decapitated heads doesn’t stick around for long. “In my experience,

people get used to the robots very quickly,” Hanson says. “As in, within

minutes.” (Guizzo 2010, 1) A 2009 empirical

study of Mori’s concept of the Uncanny Valley concludes by claiming that,

contra Mori, humanlike androids that were slightly distinguishable from humans were

not liked less than humans (Bartneck et al. 2009). For these researchers, the

future of “highly realistic androids” bodes well, and therefore, they argue,

the Uncanny Valley hypothesis no longer ought to be used to hold back the

development of such humanoid robots. Pre-Mori European

academic studies of “the uncanny” began in the early twentieth century,

although they have only a slight resemblance to Mori’s concept of the uncanny.

Ernst Jentsch’s 1906 essay “On the Psychology of the Uncanny” viewed the human

sense of the uncanny in an evolutionary context: fear of the unknown, argues

Jentsch, lies at the core of the consciousness of all living beings, and their very

existence. On this account, fear of the unknown is hard-wired into consciousness

itself – humans

experience this particular fear as the Uncanny, or Unfamiliar (Un-heimliche). While much of what is

considered “uncanny” for the modern human is either a result of primitive

baggage, various forms of intoxication, or mental derangement, claims Jentsch,

a fearful sense of the uncanny/unknown still lies at the epicenter of modern

human consciousness – which is why modern humans so aggressively cultivate the practice of “science”

(Jentsch 1996, 16). Freud’s 1919

essay on “the Uncanny” is written as a response to Jentsch. Although Freud agrees

with Jentsch concerning the innate human fear of the unknown/uncanny, he offers

a psychoanalytic interpretation of this particular fear, claiming it to be the

primitive fear of castration, Kastration

Angst (Freud 2003, 139). Neither

Jentsch’s nor Freud’s view of the Uncanny appears to have influenced Mori’s

concept of the Uncanny Valley. On the other hand, in an interesting manner,

both Jentsch and Freud discuss the uncanny in terms of the Automat robot character Olimpia who appears in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s novel

The Sandman. Neither Jentsch (1906) nor

Freud (1919) considered the kind of real-time robotic uncanniness that Mori was

confronted with in 1970. As for a more specific

Western influence on Mori’s conception of the Uncanny Valley, Norbert Wiener’s

1948 Cybernetics: Or Control and

Communication in the Animal and the Machine, entranced Mori when it was first

translated into Japanese in 1961. The “Animal in the Machine” that Wiener

predicted shared Mori’s pacifist view of the field of robotics (and Mori’s

later conception of the “Buddha in the Robot”). Although Wiener had developed

his concept of cybernetics during his war efforts during WWII (in designing the

automatic aiming and firing of anti-aircraft guns), he became a staunch

pacifist after the war, campaigning against the militarization of science. His

pacificism is already evident in Cybernetics,

which was written shortly after the war: We have contributed to the initiation of a new science

[cybernetics] which, as I have said, embraces technical developments with great

possibilities for good and for evil. We can only hand it over into the world

that exists about us, and this is the world of Belsen and Hiroshima. We do not

even have the choice of suppressing these new developments. They belong to the

age, and the most any of us can do by suppression is to put the development of

the subject into the hands of the most irresponsible and the most venal of our

engineers. The best we can do is to see that a large public understands the

trend and the bearing of the present work, and to confine our personal efforts

to those fields, such as physiology and psychology, most remote from war and

exploitation. (Wiener 1948, 38–39) When Mori the

roboticist first conceived of the Uncanny Valley, he was an avid practicing Buddhist.

From a Buddhist point of view, to be fully human requires a radical

rethinking of what it means to be a human in the first place. The given, a

priori, “human” is a being straddled with an unfulfillable desire, tṛṣṇā: the clutching

desire for the permanency of an ego-based

form of self-identity. The praxis and ethics of letting-go of this desire make way for a different sort of human, a trans-human of sorts, a “Buddhist.” Hence, from a Buddhist robotics perspective,

why try to replicate the present human in the first place, the same “human”

that one ought to overcome? In Mori’s essay, “The Uncanny Valley,” the technologically

created Viennese robotic prosthetic hand appears as a metaphor for our

recoiling from what ought to be considered unfamiliar and strange from a

Buddhist perspective: i.e., human nature circumscribed and constituted by tṛṣṇā. If

compassion constitutes the essential nature of Being, and hence the human

being, it follows that humanoid robots ought to reflect this – not uncanny or

unfamiliar, but of the essence of Buddhahood: compassion. Hence, it comes as no

surprise that Mori concludes his essay with a reference to a Buddha of Compassion’s

wooden hand, suggesting that this hand may be less uncanny and unfamiliar to

human beings than a realistic prosthetic. From a Buddhist perspective, the

world of the human is fake enough: there is no need to make it more fake. The Buddha in the Robot “Man will never

reach the moon regardless of all future scientific advances.” – Dr. Lee De Forest,

inventor of the Audion tube and a father of radio, 25 Febuary, 1967. In his book, The Buddha in the Robot, written some four

years after “The Uncanny Valley,” Mori does not once mention the concept of the Uncanny Valley, although the Buddhist

subtext of his essay permeates the book. The “healthy person” is no longer

considered to be at the apex of the familiar or the likeable: that apex is

attained with the enlightened insight of Buddhist prajñā (Enlightenment). The world itself is afflicted by

ignorance, claims Mori, “which is seen in Buddhist philosophy as the

fundamental cause of all evil” (Mori 1981, 8). In the 1981 preface to the English

translation of the Buddha in the Robot,

Mori articulates an overly exuberant and naïve view of Buddhism as “the truest,

the most perfect, the most universal, and the most magnanimous of religions”

(Mori 1981, 9). Taoism, Confucianism and Shintoism are surprisingly not

mentioned in this book, although if one were to comprehensively treat the issue

of robots and AI in 1981 in Japan, in terms of “traditional” Japanese culture, one

would no doubt have to treat the contributions of these three other Japanese

traditions. Clearly, as

both a Pure Land and Zen Buddhist, Mori shows a perspective that is characteristic

of modern Japanese Buddhism, which emerged out of its persecution during the

Meiji Era ((明治時代 Meiji-jidai, 1868–1912). During this period, Buddhism was

censured as “a corrupt, decadent, antisocial, parasitic, and superstitious creed,

inimical to Japan’s need for scientific and technological development” (Sharf

1995, 110). However, instead of conceding defeat, Japanese Buddhist leaders

developed what came to be known as New Buddhism (shin bukkyō), which was considered “true” or “pure” Buddhism, and

“which was found to be uncompromisingly empirical and rational, and in full accord with the findings

of modern science” (Sharf 1995, 110). Although Mori himself does not

self-identify his Buddhist persuasion with “New Buddhism,” or with any

particular sect of Japanese Buddhism, in the Buddha in the Robot, the membership of his Mukta Institute held

both Pure Land and Zen Buddhist views (Schodt 1998, 207). Although in no way possessing the

philosophical acumen of the notable Japanese Buddhist philosopher Nishida

Kitarō (1870–1945),

Mori, as a roboticist, not a philosopher, expressed insights with which Kitarō

would no doubt have agreed. They would have agreed that Buddhism’s basic

principle or insight is that all

things in the cosmos are manifestations of the primordial Buddha-nature of Enlightenment,

Compassion, and Nothingness/Emptiness. Hence, Mori, without hesitation, claims

in this book that “robots have the buddha-nature within them – that is, the potential

for attaining buddhahood” (Mori 1981, 13). The

Buddha in the Robot also contains the messianism of Pure Land

(Amitāba-Buddha/Sukhāvatī) Buddhism, as, for example, when Mori

states that his robot’s call is loud and clear: “The more mechanized our

civilization becomes, the more important the Buddha’s teaching will be to us

all” (Mori 1981, 57). In the late 1980s,

Frederik L. Schodt had the opportunity to attend a meeting of Mori’s Mukta Institute. Schodt describes a

typical meeting of this group: As part of this process, Mukta members regularly meet

to recite Buddhist scriptures, meditate, and attempt to consider problems in

new ways. On the wall of the room in which the meetings are held, along with

Buddhist calligraphy, is an elaborate clock with no hands that tells no time;

in the center is a yin-yang shaped table that can be split in half and

reconfigured in a myriad of ways to encourage different methods of

communication. Here the members imagine new robots, cars, and methods of

automation, and, as [member] Matsubara says with a chuckle, “occasionally sip

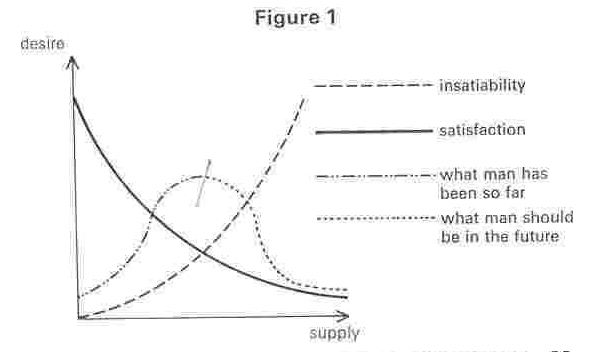

some sake.” (Schodt 1998, 210) The Buddha in the Robot contains a graph,

not of the Uncanny Valley, but what could be described as the Tṛṣṇā Valley – the valley of desire. For

Mori, the implications of mass social roboticization are not the modern human’s

most pressing issue. This is human suffering, which is ultimately caused by desire: “the cause of all suffering is

rooted in desire.” Mori describes the Buddhist understanding of the process of

desire with the analogy of a bomb (which resonates with the pacifistic

declaration of Article 9): “one burning desire ignites other desires around it,

and the fire spreads as in the bomb. The more we feed desire, the more it

grows, until it becomes an explosive form of insatiability” (Mori, 1981, 55). In

the graph that follows, Mori plots the point at which the modern human being

exists on a scale of “desire.” A “natural” balance exists in nature, he argues: “there exists in nature a desire that knows

satisfaction – a

desire that does not go beyond certain limits. This moderated desire is the

principle that underlies the harmonious workings of nature” (Mori 1981, 56).

The solid line in the graph represents these ‘harmonious workings of nature,”

as a balance between our desires and their appropriate satisfaction (“supply”) (Mori

1981, 56):

In order to

function properly alongside robots, and to welcome humanoid robots in our

social world, argues Mori, we must first learn how to control our own desires,

our own tṛṣṇā for

ultra-existential ego-permanency: we must first learn how to understand and

embrace both compassion (karuṇa)

and nothingness (śūnyatā).

In his Loving the Machine: the Art and

Science of Japanese Robots (2006), Timothy Hornyak responds to the question

as to why humanoid robots are apparently so loved in Japan: “simply because

they are simultaneously science and fiction” (Hornyak 2006, 157). Mori would no

doubt agree, but for Mori, the Buddhist

roboticist, this love results from an insight that humanoid robots are also

part and parcel of the oneness of all

things, of Buddha-nature – of Enlightenment, Compassion and Nothingness/Emptiness. The conference comments In 2005, thirty-five

years after Mori first proposed the concept of the Uncanny Valley, he was

invited to a conference, Views of the

Uncanny Valley: A Humanoids 2005 Workshop, held in Tsukuba, Japan, which addressed

the concept in terms of psychology, sociology, philosophy, neuroscience, and Artificial

Intelligence. He sent a letter to Karl MacDorman, the director of the Android

Center at Indiana University, and the one person who has carried out extensive

empirical studies on the idea of the Uncanny Valley; Mori declined the

invitation, due to prior commitments. In this letter, which has been posted on

the net, he states that “while I introduced the notion of the Uncanny Valley, I

have not examined it closely too[sic]

far” (Mori 2005, 1). Nevertheless, he included two short personal observations

regarding the concept of the Uncanny Valley, both of which are critical of its

original formulation: he is critical of his formulation of both the low point

(a corpse) in the curve of the Uncanny Valley, and the high point (the healthy

person). In his 1970

article, the Uncanny Valley is placed between the experience of a corpse and a

zombie. By 2005, Mori has changed his attitude toward the corpse. The corpse is

no longer an object to be considered “uncanny.” It is now something about which

to rejoice: it no longer has to suffer, which is the fate of all living beings. The essence of human

existence, he states in his first observation, is the fact that humans suffer,

and are therefore troubled, which often shows on their faces. Here, Mori uses a

Buddhist tṛṣṇā

argument to explain why a human corpse should not be viewed as something

uncanny, but as something more real than the living form of human life-consciousness. He cryptically gives a

reason for human suffering, i.e., the very act of decision-making: “if you take

one thing, you will lose the other” (Mori 2005,1). Whenever one makes a

decision about one’s life, in this way or that, one always wonders whether or

not the decision made was the right one. It is as if, with every little

decision, one encounters a death of sorts in the choice that was not made. In

life, one cannot have one’s cake and eat it too: this is the reality of desire.

By contrast, the corpse is free of such desire. Based on a clearer

understanding of his Buddhist principles of oneness and compassion, Mori no

longer appears, in his 2005 observation, to be struck by the significance of

the experience of the uncanny. By way of comparison, Freud, when he was in his

sixties, also had a personal observation about the uncanny in his essay on The Uncanny. He observed that the older he

had become, the less a sense of the uncanny operated as an experiential aspect in

his life (Freud 2003, 124). In his second

reflection in the 2005 letter to Karl MacDorman, Mori addresses the “high point”

of the curve, the healthy person. Upon reflection, he states, Buddhist statues

that bring out the compassionate and healing nature of enlightened-consciousness ought to be held as the ideal of human

existence, not “the healthy human” per se. He states that the faces of the representations of the compassionate

nature of the Buddha “are full of elegance, beyond worries of life, and have an

aura of dignity” (Mori, 2005, 1). Such artistic representations, he claims, should

replace the highest value of “the healthy human” in his 1970 graph. From these two

reflections in 2005, it is clear that Mori is rearticulating his view of both

humanoid robots and artificial intelligence that he articulated in The Buddha in the Robot – that all is one and infused with “buddha-nature.” In 2011, at the age of 84,

Mori acknowledged the existence of the Uncanny Valley, but simply as a design

glitch in the field of humanoid robotics: “To a certain degree, we feel empathy

and attraction to a humanlike object; but one tiny design change, and suddenly

we are full of fear and revulsion” (Kawaguchi 2011, 1).” This, he says, is what

he has described as “the uncanny valley.” Yet, he still articulates the view of

humanoid robots and artificial intelligence found in The Buddha in the Robot, concerning the oneness of all things: I call that its “Buddha nature;” robots, plants,

stones, humans, they’re all the same in that sense, and since they all have a

spirit, we can communicate with them.

For example, when a door hinge makes a sound, it’s crying “Please oil

me!” I converse with chopsticks: “Thank you!” for letting me use them, I

say. They reply, “No problem! This looks

delicious! Enjoy!” (Kawaguchi 2011, 1) Conclusion: Masahiro Mori’s Buddhist-based

transhumanism – human transformation or human transmogrification? Based on the

preceding discussion, one might conclude that, according to Mori’s robotic-engineering-based

Buddhist philosophical perspective, the Uncanny Valley is similar to the Buddhist

concept of impermanence coupled with its concomitant quality, suffering (duḥkha). Like the Buddhist concept

of suffering, the Uncanny Valley can be metamorphosed into something transformative.

Likewise, Gautama Buddha’s experience of sick, elderly and dead humans

originally engendered a sense of horrific uncanniness

in the young princeling, but upon his becoming Enlightened, he viewed such

uncanniness as part and parcel of the fabric of this world, the fabric of “impermanence/nothingness,”

which he approached with compassion. While it appears

to be the case that all things are One, it also appears that all things are not

One, as both Heraclitus and Lao Tzu would commiserate. Human beings appear to live

in the dichotomy of being One with all that exists, while also existing as significantly

separate from this Oneness. Mori clearly obfuscates this dichotomy, which is a

serious philosophical flaw in his thinking when it comes to the existence of humanoid-like

AI and robots, given the significance and dignity of self-identity qua individuality. As well, as a self-proclaimed practicing

Buddhist, Mori appears predisposed to embracing humanoid-like robots and AI on the

basis of his predilection for the anime-like

figure of “the Buddha” as he exists as a phantasmagorical construct in Buddhist

hagiography (such as in the Mahā-Parinibbāna-Sutta)

and in Buddhist iconography. Mori’s openness towards the idea that humans ought

to give up their humanity as “humans”

to the “oneness of all things” in the

guise of robots and AI exhibits the same naiveté

that he displays in his book The Robot in

the Buddha concerning the virtues of Buddhism as “the truest, the most

perfect, the most universal, and the most magnanimous of religions.” Masahiro Mori

can be described as a Buddhist “transhumanist,” and as an advocate of transhumanism.

Hence, he falls within the fuzzy crosshairs of the “Westernist” historian-of-ideas

Francis Fukuyama, who has characterized the philosophy of transhumanism as the

world’s most dangerous idea – one that aims to “deface

humanity” (Fukayama 2004, 43). Whether the Buddhist-based transhumanism

advocated by Masahiro Mori prefigures a utopian human transformation, a

dystopian human transmogrification – or both, or neither – only time will tell. But then, time itself is a relative concept, as

is the concept of nothingness. Notes This article has been translated into Chinese by Shao Ming and was first published in 2012 in the Journal of Yibin University 12 (8) (August): 1-7. Available at: http://goo.gl/rbazjX. (accessed Dec. 10, 2013) 1. The Shinto

consecration of robots faded out in the late 1980s, as an official at Kawasaki

explained: “We have too many to name now” (Geraci 2006, 8). 2. The word “Karakuri”

refers to a mechanical device to tease, trick, or take a person by surprise. It

implies hidden magic, or an element of mystery. In Japanese, “Ningyo” is

written as two separate characters, meaning person and shape. It loosely

translates as “puppet,” but can also be seen in the context of a doll or even

effigy (Law 1997, 18). 3. Interestingly, in light of

Mori’s concept of the Uncanny Valley, WWII was precipitated by the Great

Depression of the 1920s, which is referred to in Japan as the era of the “Dark

Valley” (kurai tanima, 暗い谷間). 4. In this

context, it should be noted that Fritz Lang’s Metropolis was released in Japan in 1929, and Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. was translated into Japanese in

the 1930s. 5. Mori’s

techno-utopianist doppelganger in the West could be viewed as the

roboticist/technophile Ray Kurzweil,

many of whose significant technological activities (e.g., voice

recognition software) have been conducted under the aegis of DARPA (the Defense

Advanced Research Projects Agency), the scientific wing of the American

military high command. Geraci views the majority of contemporary Japanese

roboticists as just as misled as their utopian American counterparts, since

both groups are heedless of “the potentially disastrous effects of robotic

technology” because of their heady eschatological and soteriological cultural

baggage (whether it be a mix of Shintoism-Confucianism-Buddhism or a form of

Judeo-Christianity): “even though they may be agnostic or even atheistic,

[‘pie-in-the-sky’] religion maintains some power over their work” (Geraci 2006,

11). 6. “I belong to

the Atom generation,” declared Asimo’s prime mover, Toru Takenaka, the chief engineer

at Honda R&D Co. Ltd. “When I was a child, I loved Atom [Boy] and Tetsujin

28 [another cartoon robot], and I used to be immersed in the robot world (Hara

2001, 1).” As a graduate of the Mukta Institute, Soichiro Honda, the founder of

Honda Motors, has developed his company along Mukta Institute principles

(Schodt 1998, 209). 7. Mori does not

describe the wooden hand as typical of a representation of Avalokiteśvara,

the Boddhisattva of Compassion, who also exists in the form of Padmapāni,

the One with a Lotus in His/Her (ardhanārīśvara-rūpa)

Hand, always the left hand. The right hand is often lowered in a compassionate

gesture of giving a blessing (a varada-hasta

as a varada-mudrā). The wooden

hand sculpted along Buddhist principles appearing in the original Japanese

version of the article is just such a hand:

8. Joshua Davis

was the digital artist who created the non-Uncanny-Valley Watson avatar:

See: http://goo.gl/bSJHiG (accessed September 13, 2013). References Bartneck,

C., Kanda, T., Ishiguro, H., and Hagita, N. 2009. My robotic doppelganger – A critical look at the Uncanny

Valley theory. Proceedings of the 18th

IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication,

RO-MAN2009, Toyama, 269–276. (accessed April

20, 2013). Davis, Joshua.

2011. What is Watson? The face of Watson. Vimeo.

http://goo.gl/RrcDTq (accessed

April 28, 2013). Freud, Sigmund.

2003. The uncanny. New York: Penguin

Books. Fukayama,

Francis. 2004. Transhumanism. Foreign Policy 2004–09–01. Geraci, R. M.

2006. Spiritual robots: Religion and our scientific view of the natural world. Theology

and Science, 1–16. http://goo.gl/BVPFmc (accessed Dec. 9, 2013). Government of

Japan. 2007. Long-term strategic guidelines,

“Innovation 25 .” 1–97. http://goo.gl/FKDpnv (accessed April 28, 2013). Guizzo, Erico.

2010. Who’s afraid of the Uncanny Valley?

IEEE Spectrum: Inside Technology http://goo.gl/BtX5b2 (accessed April 29, 2013). Hara, Yoshiko.

2001. Humanoid robots march to market in Japan. EE Times. http://goo.gl/wXdBAB (accessed April 28, 2013). Japan: Robot Nation. 2008. Current TV. Vanguard

Season 2, Episode 8. http://goo.gl/TYtnX0 (accessed April 27, 2013). Jentsch, Ernst. 1996. On the psychology

of the uncanny (1906). Translated by Roy Sellars. Angelaki 2.1, 17-21 . (Originally

published 1906.) Hornyak, T.

2006. Loving the machine: The art and science

of Japanese robots. Tokyo: Kodansha International. Kawaguchi,

Judit. 2011. Words to live by: Robocon founder Dr. Masahiro Mori. The Japan Times on Line, March 10, 2011.

http://goo.gl/K4D2Wh (accessed April 26, 2013). Law, J. M. 1997.

Puppets of Nostalgia. Princeton: Princeton University Press. MacPherson,

Kitta. 2009. Like humans, monkeys fall into the “Uncanny Valley.” News at Princeton. http://goo.gl/hBt9vg (accessed April 29, 2013). Mori, K., and

C. Scearce. 2010. Robot Nation: Robots

and the declining Japanese population. Discovery

Guides, 1–17. http://goo.gl/lRMlnE (accessed

April 25, 2013) Mori, M. 1970. The

Uncanny Valley. Energy, 7, 4: 33–35. (In Japanese.) ——— 1981. The

buddha in the robot: A robot engineer’s thoughts on science and religion, trans. Charles S. Terry. Tokyo: Kosei

Publishing Co. (Originally published in two volumes, Mori Masahiro no Bukkyō Nyūmon

and Shingen (1974).) ——— 2005.

On the Uncanny Valley, androidscience.com.

http://goo.gl/rvpUk5 (accessed

April 26, 2013) ——— 2012. The

Uncanny Valley, trans. by Karl F. MacDorman and Norri Kageki under

authorization by Masahiro Mori. IEEE

Robotics & Automation Magazine, 98–100. http://goo.gl/iskzXb (accessed April 27, 2013). Mullins, Aimee. 2009. It’s not fair having 12 pairs of legs. TED:

Ideas Worth Spreading. http://goo.gl/1nn3TP (accessed April 27, 2013).

Nakamura, M. 2002. Horror and machines in

prewar Japan: The mechanical uncanny in Yumeno Kyûsaku’s Dogura magura. Science Fiction Studies, 29, 364–381. Peters, Benjamin J. P.

2008. Betrothal and betrayal: The Soviet translation of Norbert Wiener’s early cybernetics.

International Journal of Communication. 2,

66–80. Robertson, J. 2010. TVO

(Canadian television interview), The Interview: Jennifer Robertson: Japan’s

Robot Nation. The Agenda with Steve

Paikin, 20:00, December, 15. (The interview is no longer

available on the TVO website, but exists on YouTube: http://goo.gl/nhkBLl (accessed April 27, 2013).) Schodt, Frederik L. 1998. Inside the robot kingdom: Japan, mechatronics,

and the coming robotopia. New York:

Kodansha International Ltd. Sharf, R. H.

1995. The Zen of Japanese nationalism. Curators

of the Buddha: The study of Buddhism under colonialism, ed. Donald S.

Lopez, 107-160. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Sofge, E. 2010. The truth about robots and the Uncanny

Valley: Analysis. Popular Mechanics

January 20, 2010. 1–2. http://goo.gl/IA6vFY (accessed April 28, 2013). Stokes, H.

S. 1982. Japan’s love affair with the robot. New

York Times, January 10, p. 24. The

Constitution of Japan. 1947. Chapter II: The Renunciation of War http://goo.gl/8ZcIPE UltraTechTalk.

2012. The next generation of bionic arm: A general overview. http://goo.gl/RhepLb (accessed

April 27, 2013). |