|

A peer-reviewed electronic journal

published by the Institute for Ethics and ISSN 1541-0099 24(3) – Sept 2014 |

What Is A Person And How Can We Be Sure?

A Paradigm Case Formulation

Wynn Schwartz

The Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology

Harvard Medical School

wynn_schwartz@hms.harvard.edu

Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 24 Issue 3 – Sept 2014 –pgs 27-34

Abstract

A Paradigm

Case Formulation (PCF) of Persons is developed that allows competent judges to

identify areas of agreement and disagreement regarding where they draw a line

on what is to be included as a person. The paradigm case is described as a

linguistically competent individual able to engage in Deliberate Action in a

Dramaturgical Pattern. Specific attention is given to the ability of paradigm

case persons to employ Hedonic, Prudent, Aesthetic and Ethical perspectives in

choosing their Deliberate Actions and Social Practices.

It is sometimes said that animals do not talk because they lack the mental capacity. And this means: “they do not think, and that is why they do not talk.” But---they simply do not talk. Wittgenstein (1953)

Apparently, humanity has matured enough

for us to ask in a non-trivial way, “Are human beings the only persons we

encounter?”

Historically, we have only recognized

others who share our human embodiment as fellow persons. This matters legally,

morally and ethically since we grant people rights, privileges and protections

that are not offered to nonpersons. These rights, privileges and protections

are subject to revision. We no longer allow people to be kept as the property

of other people.

The capacity to revise and reorder

appraisals is a fundamental feature of what it means to be a person. This

includesmoral and ethical judgments, and appraisals of who is to be treated as

a person.

I am going to offer a Paradigm Case

Formulation of what we take to be a Person. Ethical and moral progress is a

fundamental possibility inherent in this conceptualization.It follows that if

we recognize nonhuman animals (or other entities) as persons, asking, if we are

holding them in slavery becomes a legitimate question.

What

is a person? And what is a Paradigm Case Formulation?

Sometime in the mid 1960’s, NASA asked

the Descriptive Psychologist, Peter Ossorio, “If green gas on the moon speaks

to an astronaut, how do we know whether or not it is a person?” (Schwartz

1982). Note that simply asking this

question acknowledges the possibility of a person who does not share human

embodiment.

So how can we sort out what constitutes

a person if we allow that the category is not based only on having a particular

body? Toward this goal I am going to use

the Descriptive Psychological method of Paradigm Case Formulation (PCF)

(Ossorio 2013). I will show how it is

reasonable to include non-humans as persons and to have legitimate grounds for

disagreeing where the line is properly drawn. In good faith, competent judges

using this formulation can clearly point to where and why they agree or

disagree on what is to be included in the category of “Persons”.

I am going to make explicit what is

already implicit in what we mean by "Persons" by making explicit what

we already know and act on. We already have an implicit understanding of

what it means to be a person since this understanding is fundamental in order

to act as one of us with the shared

expectations required to competently engage in the social practices of everyday

life. We engage with our fellow persons differently than we do with what we

take to be nonpersons.

The value of a Paradigm Case

Formulation (PCF) is to achieve a common understanding of a subject matter in

cases where an ordinary definition proves too limiting, various, ambiguous or

impossible. These formulations are

helpful when it is reasonable to assume there are legitimate grounds for

disagreement about specific possible examples. I think the concept of “Person”

presents this definitional problem.

A PCF should provide competent users a

starting point of agreement. PCFs are designed to be as inclusive as possible

in order to capture, as a starting point, all possible examples. Generally they should consist of the most

complex case, an indubitable case, or a primary or archetypal case. It

should be a sort of “By God, if there were ever a case of “X”, then that’s it.”

Finding a fully inclusive definition is

a common conceptual dilemma. Consider how difficult it is to exactly define

what is meant by the word “family” or the word “chair” if we wish to achieve

agreement on all possible examples of “families” and “chairs”. Must

families all have two parents of different genders plus their children?

Must all chairs have four legs and a backrest?

For example, most would agree that a

group of people living together consisting of a married father and mother and

their biological son and daughter is a family. But what if there is only a

husband, his husband and their dog? Or three best friends who live under one

roof and make their significant decisions together? What elements must be

present and what can we change, add or leave out and still meet what different

people call a family? Notice the parameters of gender, number of participants,

presence or absence of marriage, presence or absence of children, presence or

absence of “living together” and so on.

The content of each of these parameters is subject to deletion or

substitution, with the result that with each alteration a judge may no longer

accept the new variation as within the domain of what they take to be an

appropriate instance of the concept in question.

By starting with a paradigm case that

everyone easily identifies as within their understanding of a concept, it

becomes possible to delete or change features of the paradigm with the

consequence that with each change some people might no longer agree that we are

still talking about the same thing. But because of the shared paradigm, it

becomes possible to show where there is agreement and disagreement and where

various judges draw the line.

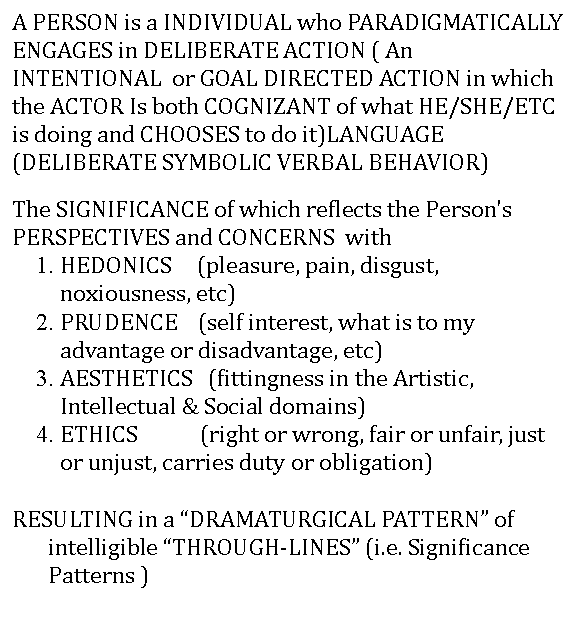

A Person

is an individual whose history is, paradigmatically, a history of Deliberate Action in a Dramaturgical Pattern. Deliberate Action is a form of behavior in

which a person (a) engages in an Intentional

or Goal Directed Action, (b) is Cognizant

of that, and (c) has Chosen to do

that. A person is not always engaged in a deliberate action but has the

ability to do so.

Deliberate Action is fundamental to any

claim of personal autonomy insofar as autonomy is linked to the ability to make

personal choices. As deliberate actors,

Paradigm Case Persons act on Hedonic,

Prudent, Aesthetic and Ethical reasons when selecting, choosing

or deciding on a course of action. Why only these four? These are the ones we

know. There may be more; if another is invented or discovered, it would be

included, somewhat like cooks now agree there is a fifth taste, umami, in

addition to sweet, sour, bitter, and salty.

Hedonics, prudence, aesthetics, and

ethics provide intrinsic or fundamental motivation (Ossorio 2013). They provide

reason enough to do something. They stand on their own. These reasons for

action can be in conflict, operate in a complementary or independent fashion,

and so on. Tautologically, if you have two or more of these reasons to do

something, you have more reason than if you had only one of them.

These four classifications are

"family resemblance groups". Hedonics refers to the value of

pleasure, pain, disgust, and so on; prudence to self-interest; aesthetics to

the artistic, social and intellectual values of truth, rigor, objectivity,

beauty, elegance, closure and fit; ethics with right and wrong, fairness and

justice, the level playing field, the Golden Rule and kindred notions.

Hedonic and prudent motivations can

operate with and without cognizant awareness. They can be an aspect of both

deliberate and non-deliberate intentional action. As a fundamental aspect of

the general case of goal directed behavior, they are probably features of

all sentient animal life, whether human or not. They provide a basis for

cross species empathy and shared understanding. I can be sensitive to my dog’s pain. I have reason to believe he is sensitive to

mine.

Aesthetic and ethical motivations are

in an important way different from hedonic and prudent concerns. Aesthetic and ethical motivations are only

relevant when deliberate action is also possible since aesthetic and

ethical action require the ability to choose or refrain, to potentially

think over a desirable course to follow. In the service of being able to

choose, and perhaps think through the available options, a person’s

aesthetic and ethical motives are often consciously available (Schwartz, 1984).

It is reasonable to claim that I can’t

help but that it feels good, or that I see it as in my self-interest. I

simply and directly know it that way without having to deliberate about it, but

as a mature paradigm case person, I can consciously attempt to refrain from

seeking pleasure or self-interest on aesthetic and/or ethical grounds. And, at

times, I might set my ethics and aesthetics aside for the sake of pleasure and

self-interest.

It is a matter of one's personal

characteristics how an individual weighs their hedonic, prudent, ethical and

aesthetic reasons in a given circumstance, and how these perspectives operate

independently, antagonistically, harmoniously, and so on. To

remain a member in good standing in the general community of persons, central

to our social contracts, we expect that the normal mature human can employ all

of these motivational perspectives. Any

adult human who does not have these interests will likely seem primitive or

pathological. Any general theory of human behavior that does not

adequately address these motivations will be defective.

It is the formal requirement that

ethical and aesthetic acts are potentially deliberate that positions these

motives as quintessential qualities of persons. Any action that is motivated

by ethical or aesthetic concerns is evidence of the involvement of a

person.

What about language?

Also paradigmatic of persons is

language use, the ability to share symbolic representations that correspond to

the concepts used in social practice.

The detection of language is both vital and problematic in assigning the

status of person to a nonhuman entity.

Shared social practice based on shared "forms of life",

as Wittgenstein (1953/2009) put it, creates a dilemma since both embodiment and

environment are relevant in what is shared.

Evidence of language is vital in the detection of deliberate action

since with language we can symbolically represent a choice, both what was

chosen and what was renounced. I can

tell you what I did and what I decided not to do. Language may not be required

for a particular deliberate action to be possible, but it hard to get around

its central place in the detection of persons.

We don’t have direct access to what

goes on in another person’s head. We can only observe each other's overt

performance, including what we tell each other about what we are up to.

Language is the ideal format for representing option and choice, since we can

speak about what we did not do, what we rejected or refrained from.

You see me take the low road but unless

there is some way of representing that I was aware that I could have taken the

high road, you might be hard pressed to successfully argue my behavior was

deliberate and that I am accountable for the choice.

Language is especially significant

in a person's ability to reorder priorities. Since language can be used

to represent the consequences of a course of action not yet followed,

it serves as a fundamental means of personal and social negotiation. I can

weigh the consequences of my potential acts and you can tell me your

thoughts about them. The reordering of priorities is a vital aspect

of social life, hard to accomplish without language.

This is also partly why

the behavior of persons is less stereotyped and predictable than

the behavior of nonpersons. People can develop, invent and reconsider. They can

think about their thinking. They can change their mind (or at least they

can try). And, central to my interests in this writing, people can gather

evidence that an entity they had not considered a person might be one.

What about the Dramaturgical Pattern?

That life is lived in a dramaturgical

pattern is to say that people’s lives are potentially understandable.

Their stories can be intelligibly told. Life consists of episodes of

unfolding and overlapping social practices in response to the changing

circumstances. A person’s history is not

a random or arbitrary collection of performances but instead a meaningful

unfolding of behavior given what a person is attempting to accomplish. A person’s actions have an ongoing

significance creating intelligible through-lines that an observer can employ in

recognizing behavior that is both in and out of character for the actors (Schwartz

2013). Of course, accidents and the unintended can happen; but for the most

part, people have their reasons for doing what they do. The drama of a person’s life is created in a

manner akin to an improvisational play. The characters and the setting are a

given but we have to wait and see how it will play out. The script can only be

written in retrospect, after the actions have occurred.

The PCF offered here allows for

nonhuman persons, potential persons, nascent persons, manufactured persons,

former persons, deficit case persons, primitive persons, and, I suppose,

super-persons. A human being is an

individual who is both a person and a specimen of Homo sapiens (Ossorio

2013).

I am not going to include the political

and legal claim that corporations are persons since that involves a language

game that is played for different reasons than my concerns here. Corporate

personhood has its own logic of contract and responsibility.

Some implications

Although deliberate action is not

dependent on the availability of language, language use is a form of

deliberate action essential for the full paradigm. A person

without language would be a deficit case. Different judges will have

their reasons for granting or rejecting a deficit case as a full person along

with the corresponding rights, obligations and expectations that follow from

that accreditation or degradation (Schwartz, 1979).

Must a person have an ethical and

aesthetic perspective to count as a person? Or is the ability to engage in any

sort of deliberate action enough? Clearly to me, my dog Banjo is a deliberate

actor. But our conversations are pretty

one sided. He has, I feel sure, hedonic and prudential perspectives. About his ethical and aesthetic perspective,

I am not sure, except that I think I would have a hard time building a case

that he has these values. I think he appreciates affection and gentleness

similar to me, but I would not trust him with my lunch. I do not doubt that he

is an intentional actor, although I am uncertain about the range and nature of

his deliberations. But regardless, apart from the extent I consider Banjo

to have some person qualities, he is a member of my family and is to be treated

as such. He is a beloved companion.

The ability to weigh hedonic,

prudent, ethical and aesthetic interests are defining personal characteristics

since these perspectives shape an individual's social practices and ways

of life. The dramaturgical pattern of a

particular life is significantly dependent on a person’s values. A robot or

manufactured person, given its physical form, might not have an hedonic

perspective since the visceral sensations of pain or pleasure might not be

available; a chimpanzee person, apparently lacking language, probably has

underdeveloped or absent ethical and aesthetic concerns and this suggests a

sort of primitive status. Still, underdeveloped is different from

absent. Our descendants may look back at

our values and see them as underdeveloped.

We are a work in progress.

The line that constitutes language use

from nonlinguistic communication is also blurred. Evidence that chimpanzees and

other Great Apes use a flexible system of non-vocal gestures to communicate may

reasonably be considered a “sign language” by some observers (Hobaiter and Byrne,

2014).

Human children, while developing their

perspectives, have nascent person status and are treated differently than full

“legal” persons by not being given the same span of rights and responsibilities

granted adults. But the distinction

between childhood and adulthood is clearly arbitrary. Is adulthood reached at

21, 18, 16, 12, or 35? Rights and obligations change as values, knowledge and

competence matures but is finally a matter of political and legal decision.

The PCF provides a way to classify

different sorts of persons based on the motives they are competent to use in

recognizing their options and choosing a course of action. The ability and disposition to manifest and

refine hedonic, prudent, aesthetic and ethical values are fundamental status

markers relevant to a consideration of appropriate rights and responsibilities.

Implicitly or explicitly we employ these distinctions in our interactions with

others whether adult or child, human or otherwise.

What about other animals?

Years back, I was pursuing a pod of

bottlenose dolphin when a small one smacked the stern of my kayak, hard.

As the calf re-approached, a large female nudged it away. I was

astonished, relieved and grateful. Not wanting to push my luck, I paddled back

to shore.

Are dolphins good candidates for

personhood? Do they engage in deliberate action in a dramaturgical

pattern? Do bottlenose dolphins speak to each other? Did a dolphin

protect me from mischief? I don't know.

I don't have sufficient evidence that dolphins fill the paradigm case. Some people have reason to think they might.

Using a PCF, I can point to where the evidence is robust and where it is

lacking. Language seems to be the

sticking point.

What about the other Cetacea, the elephants, the nonhuman

primates, and various parrots? I suspect

they fill out some of the paradigm case. Other judges reasonably believe they

fill out more. To the extent other animals are not domesticated (or enslaved),

they can’t or don’t "talk" with us.

Nonhuman animal communication, including the possibility

of language use, is difficult to study when there is an absence of

"shared forms of life."

The domesticated

are interdependent with humans in a way other animals are not and

this partly accounts for my sense of their companion status and our shared

practices. We work, play, eat, exploit and otherwise interact with the

domesticated in ways we do not with the "wild". They become our pets, livestock, guards and companions. We treat them, for better or worse,

accordingly. As our ethical and aesthetic

standards evolve, we revisit what we take to be the right way to engage with

them (or we should).

Do animals in the wild talk with each

other and could they talk with us? We may not have sufficient shared

social practices to make inter-species communication, speech, and translation

feasible, so it’s very hard to tell. This is a difficult empirical issue. Rather than simply communicate, some

observers believe they speak to each other in a linguistic fashion. There is no

consensus but the evidence is mounting that they do (see, for example,

Savage-Rumbaugh, 2009).

Since language requires shared social

practice, an animal’s ecologically bounded options limit its expected

communicative range, concerns, and actions. Humans are adept at disrupting

their environments. We’re very skilled

at coercing them and killing them to further our goals. If they wanted to

talk to us, I am not sure we’d welcome what they have to say.

If someone actually taught

nonhuman animals to competently use language, would that be teaching them to be

a person? Yes, that is an implication of the paradigm offered here. By this same reasoning, we teach our human

children to be persons, too.

What are the ethics of uncertainty?

So what should we do with our

uncertainty? Logically, we are never in a position to prove that something is a

person, but we can adopt a policy that if we have any strong grounds for seeing

the other as one of us, we should treat that entity as a person until we have

reason enough to feel we are misguided. With persons it should be I to Thou.

There are people whose cultures and social practices leave me mystified, but it

is prudent and ethical to proceed from the belief that I simply do not

understand what they are about. The same

should hold for other animals.

I am not particularly concerned with

initial false positives. In my scientific training, I was told to avoid

anthropomorphism. I have become skeptical about the morality of this

stance, whether it involves an animal’s possible slavery or how I treat them as

food.

A significant ethical question remains:

After the line on personhood is drawn, what considerations apply to the

treatment of animals that do not fall into the person category? Sentient

animals are intentional actors and have an interest in the avoidance of

suffering (Singer 2009). Is it ever

ethical to inflict harm if there is a way not to? What priorities need be

weighed?

Person status defines a domain where

social and legal rights reside, hence a proper abhorrence of slavery and murder.

Judges in good faith might differ as to what animals are included as

persons, but it is a moral and ethical mistake to limit concerns about the

quality of a life to whether that life is also a person. Part of being a

person is to understand this.

References

Hobaiter and Byrne. (2014)The Meanings of Chimpanzee Gestures,

Current Biology. Accessed:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.066

Ossorio, P. 2013. The Behavior of Persons. Ann Arbor: Descriptive Psychology Press

Savage-Rumbaugh, S., D.Rumbaugh, W.A. Fields. 2009. Empirical Kanzi: the ape language controversy revisited. Skeptic. 15(1): 25-33.

Schwartz, W. 1979.Degradation, Accreditation and Rites of Passage.Psychiatry. 42(2): 138-146.

Schwartz, W. 1982. The Problem of Other Possible Persons: Dolphins, Primates, and Aliens. In Advances in Descriptive Psychology vol 2.ed. Davis, K. and T. Mitchell, 31-56, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Schwartz, W. 1984.The Two Concepts of Action and Responsibility inPsychoanalysis.The Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 32: 557-572

Schwartz, W. (April, 2013) Through-lines, the Dramaturgical Pattern, and the Structure of Improvisation.Accessed:http://freedomliberationreaction.blogspot.com

Singer, P. 2009. Animal Liberation. New York: HarperCollins.

Wittgenstein, L. 1953/2009, Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.