|

A peer-reviewed electronic journal

published by the Institute for Ethics and ISSN 1541-0099 26(2) – September 2016 |

Confronting Existential

Risks With Voluntary Moral Bioenhancement

Vojin Rakić

Center for the Study of Bioethics, Institute for Social

Sciences, Serbian Unit and European Division of the UNESCO Chair in Bioethics,

Cambridge Working Group for Bioethics Education

University

of Belgrade

Milan

M. Ćirković

Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade

and

Center for the Study of Bioethics

University

of Belgrade

Journal

of Evolution and Technology -

Vol. 26 Issue 2 – September 2016 - pgs 48-59

Abstract

We outline an argument favoring

voluntary moral bioenhancement as a response to

existential risks humanity exposes itself to. We consider this type of

enhancement a solution to the antithesis between the extinction of humanity and

the imperative of humanity to survive at any cost (e.g., by adopting illiberal

strategies). By opting for voluntary moral bioenhancement,

we refrain from advocating illiberal or even totalitarian strategies that would

allegedly help humanity preserve itself. We argue that

such strategies, by encroaching upon the freedom of individuals, already

inflict a degree of existential harm on human beings. We also give some

pointers as to the desirable direction for morally enhanced post-personhood.

Introduction

A sizeable body

of literature has been devoted recently to arguments for and against cognitive

and/or moral enhancement of human beings. Harris, Savulescu,

Persson, Douglas, Crockett, Wilson, DeGrazia, Agar, Sparrow, Rakić,

Wasserman, Wiseman and others have written various articles and books on the

topic, but a truly comprehensive recent review of the literature is still

lacking.

Bioconservatives have

argued against bioenhancement, as they believe that

it is aimed at intervening in what has been ordained by God or given to us by

nature. Bioliberals, on the other hand, insist that nature

is morally indifferent, from which it follows that we have a right to intervene

in what nature has created. In fact, we do that already when we fight certain

natural phenomena that inflict harm on people: e.g., medications are

administered to patients who suffer from diseases (which are frequently

naturally occurring phenomena), dams are built to contain floodings,

defenses against lightning are set up. Some bioliberals insist on our moral duty to enhance everything that can be enhanced. On the other hand,

there are those who are against certain forms of enhancement but are by no

means bioconservatives. For instance, they are

against moral bioenhancement, at least in its

currently possible form, but are not necessarily against cognitive bioenhancement (e.g., John Harris and Nicholas Agar).

It is precisely

the theme of moral bioenhancement that figures

prominently in bioethics literature in recent years. Persson

and Savulescu assert that humanity is at risk of

(self-) annihilation, or another form of what they call “ultimate harm,” if it

does not embark on the path of moral bioenhancement.1 John Harris,

on the other hand, maintains that this type of enhancement can be accomplished

only to the detriment of our freedom. He insists on cognitive enhancement being

sufficient for moral enhancement (Harris 2011). Rakić

(2014) argues against both Harris and the collaborative efforts of Persson and Savulescu. Against

Harris, he maintains that

we might become cognitively enhanced, e.g., we might start to understand that

racial prejudices are morally wrong, without acquiring the motivation to act

upon this understanding. At the same time, Rakić

argues against Persson and Savulescu’s

position that moral enhancement ought to be made compulsory (Persson and Savulescu 2008, 174).2 This issue of the voluntariness of moral bioenhancement is essential for the central theme of this

paper: how to employ it in order to confront existential risks.

Existential risk prevention as a

moral imperative

Existential risks

are those in which an adverse outcome means the extinction of Earth-originating

intelligent life or the permanent and drastic destruction of its potential for

desirable future development (Bostrom 2002).

Recent work in existential risk analysis has clearly suggested that any form of

consequentialist ethics imposes a strong obligation to prevent global

existential threats (e.g., Parfit 1984; Matheny 2007;

Baum 2010; Bostrom 2013).

Examples of

existential risks include large natural hazards, such as supervolcanic

explosions, large anthropogenic risks, such as misusing biotechnology to create

new pathogens against which the human immune system has no defense,

and risks following from a complex interplay between anthropogenic and natural

processes, such as global warming. All these share the fundamental feature that

they can, on timescales short by astronomical, geological, or evolutionary

standards, annihilate all the values created by humanity so far, as well as all

the values which could ever be created by

humanity or its descendants. This fundamental property automatically makes the

concept of existential risk of central importance to moral philosophy in

general, and to bioethics in particular. The same property puts existential

risks into a separate category from other large catastrophic risks such as

tsunamis or ice-ages, which do not (in their

well-defined ranges of severity) threaten the very existence of future

generations of human or posthuman beings. A separation

in our ethical thinking about

existential vs. global catastrophic risks should occur even if the physical causative mechanism of some

existential risks is, in fact, the extreme part of the distribution of similar

global catastrophic risks. An astronomer might consider a 20-kilometer asteroid

impact, which would certainly destroy humanity, as essentially similar to a

2-kilometer impact, which would, according to the present-day models, devastate

a continent and change the global climate, though in a completely inhabitable

way; but the consequences for moral philosophy – and, perhaps, for the

moral status of a large part, if not all of the visible universe!3 – are as different as the concept of

death is different from that of the common cold. While it is, in extreme cases,

possible to die from the common cold, this certainly would not justify stating

that the common cold is lethal, or that the moral obligation of a physician to

try everything to prevent death of a patient extends to trying everything to

prevent the patient contracting a common cold.

This is in

agreement with our intuitions that the value of future generations, which are

directly vulnerable to the

present-day existential risks, could far exceed the values created by humanity

thus far (Bostrom 2003; Ćirković

2004). Therefore, the loss of such future values could far outweigh any loss of

value in human history thus far – and such an outcome would thus

constitute the greatest evil ever faced by humankind. On the basis of such

reasoning, many contemporary researchers have reached the conclusion that

prevention and mitigation of existential risks are the biggest imperatives our

species has ever faced (e.g., Matheny 2007; Bostrom

2013).

While some

existential risks seem to be preventable with present-day or near-future

technology (impacts of large asteroids on Earth provide a prototypical example;

see e.g., Ahrens

and Harris 1992), in other cases mitigation is a more remote

prospect. The latter particularly applies to anthropogenic existential risks which, unfortunately, also have the largest

probability, such as anthropogenic global warming or intentionally caused

pandemics and other forms of bioterrorism. The huge body of literature devoted

to climate change mitigation testifies how difficult it is, and a large part of

the difficulty stems from the problem of the lack of coordination of relevant actors.4 The same

applies to the threat of misuse of biotechnology and bioterrorism (Atlas 2002;

Jansen et al. 2014), which is emphasized by the necessity of rather extreme

surveillance if preventive action is

to be possible. Similar considerations apply, mutatis mutandis, to other existential risks. All these examples

point in the same general direction: mitigation of existential risks requires a

conjunction of two key ingredients: strong global surveillance and strong

global coordination. Both ingredients are associated with a reduction, rather

than increase, of the freedom of individual actors on the scene, both personal

and political.

In line with

that, it might be argued that existential risk prevention should not take place

at the cost of our loss of freedom. If moral bioenhancement

were imposed on us by the state, our freedom would be jeopardized. As freedom

is an essential component of our humanness, its demise, either in full or to

some extent, would already inflict a

certain degree of existential harm on human individuals. In that sense, threats

to our freedom are also existential risks. Consequently, human individuals

should not fall prey to the “survival at any cost bias” (see Rakić 2014).

Moreover, we also

don’t have to accept the survival of our species as the most important moral desideratum.

Biological morality, i.e. a morality based on the survival of the species as

the highest moral goal to be achieved, is not necessarily superior to other

approaches to moral desiderata (e.g., those promoted in deontological ethics).

On the whole, we should be careful not to indiscriminately sacrifice the

essential ingredients of our humanness in order to increase the likelihood of

our survival, both as individuals and as

a species. If the cost of species survival is the

loss of its humanness, such survival would become an oxymoron.

Mitigation enforcement and the road

to totalitarianism

There are many

disturbing scenarios in which existential risks are produced by actions of

individuals or small groups (terrorist organizations, apocalyptic cults).

Particularly worrying is the possibility of the intentional or accidental

creation of new pathogens in “basement labs” lacking any biosafety measures

(e.g., Jansen et al. 2014). Mitigation of such threats seems impossible without

a drastic expansion of surveillance and curtailing of privacy, since illegal

biotech labs could easily be hidden and moved – in contrast to, for

instance, most nuclear weapons installations (and we can easily perceive from

the news how difficult it is to implement non-proliferation treaties even in

that case). An optimistic view is that this might result in a form of

“transparent society” (Brin 1998), while most

pessimistic views focus on the capacity of such technologies to create a

strictly regimented totalitarian society.

Even existential

risks with much longer timescales, like runaway global warming, might require

an extremely high level of social coordination, enforcement capability and

unity of goals, inaccessible in the context of conventionally understood

liberal and democratic societies. This becomes more and more relevant as time

passes and the measures required for mitigation become more and more extreme.

In particular, if it turns out that geoengineering is

the only efficient way to stop runaway global warming,

it is hard to see how the present, relaxed system of international deliberation

and decision-making could be employed for such an undertaking. Thus, even those

“slower” – but very much real – threats might lead rather

straightforwardly to a totalitarian or crypto-totalitarian world.

Future

totalitarianism is a stable configuration, possibly much more stable than

historical totalitarian regimes due to ongoing improvements

in technology and understanding of social and psychological mechanisms.

Ubiquitous miniaturized surveillance is already a commonplace – and has

already eroded parts of the traditional concept of privacy. Future surveillance

equipment (possibly based upon molecular nanotechnology) will be able to go

much further in that direction and entirely obviate the notion of a “private

space” that is off-limits to government or even other powerful social actors

(corporations, churches, etc.).

Another important

development that might serve as a prop of future totalitarian regimes is the

expansion of genetic screening for various functions and positions in society.

This practice might easily be abused in order to suppress any discontent and

critical thought.

Even more

speculative possibilities – although discussed in contemporary bioethics

– are also asymmetric in the sense that they are much more likely to

support illiberal rather than liberal tendencies. As argued for instance by Caplan (2008), radical life extension is more likely to

help future totalitarian regimes (for instance, to alleviate leadership

succession crises or to keep populations more conservative and docile) than it

is to help any form of liberal opposition to the regime.

Novel forms of

neurosurgery, possibly using nanotechnology, will enable more efficient

brainwashing and mind-control of opponents and potential opponents. Even in

completely different environments of the future, there will be strong

incentives for illiberal and, in the worst scenario, totalitarian regulation

(see, e.g., Cockell 2008).

Voluntary moral enhancement as the

best antidote to totalitarianism

In the context of

the discussion thus far, we submit that moral enhancement, both traditional

(education) and moral bioenhancement, is the most

promising way of “navigating between Scylla and Charybdis,” that is, avoiding

both the threat of human extinction (or a milder form of “ultimate harm”) and

“safe” global totalitarianism (or a milder form of authoritarian rule).5

Clearly, not just

any form of enhancement can help us

face our problems as a species. We need to make distinctions, and it is exactly

our ability to do this that (in our view) gives additional value to our approach:

we are in a position to proactively suggest specific

goals of moral bioenhancement. While we cannot infer

at present when such specific goals will become fully realizable, we at least

wish to argue that they are desirable,

so that further research can concentrate on specific technologies, and that any

future development can be goal-oriented. In a sense, it is a duty of

present-day bioethicists to discuss and formulate an essential toolkit for future moral bioenhancement;

the contents in the toolkit will be a function of the arguments about the

purposes and goals of undertaking the program of enhancement in the first

place.

Concretely, in

the present context of existential risk management, we suggest that acceptable

moral enhancement should contain the following two elements:

1. Long-term perspective in assessment and decision-making.

2.

Respect for the autonomy and liberty of societal

actors.

Both seem rather

obvious desiderata. Without a long-term perspective – which is sorely

lacking in the public discourse nowadays – the management of processes that

could take decades or centuries, or even more, to manifest their

effects will be impossible.6

Respect for

liberty and autonomy is an obvious barrier to totalitarian tendencies. If

historical experience is to be of any help, this ingredient seems to be

necessary independently of any other cognitive or social requirement.

In that sense, it

is critical to understand the perils of a program of compulsory moral bioenhancement. Such a

program might in the worst case lead to political

repression and totalitarianism. As already noted, Persson

and Savulescu do not advocate compulsory moral bioenhancement in their recent writings, but nor do they

take a stance against it. Consequently, their position contains the danger of

indirectly supporting illiberal tendencies. It can do so in the following way:

1.

Savulescu and Persson’s

conception of the “god machine” appears to contain an illiberal component. The

“god machine” is a device that obliterates our wish to perform an immoral act

as soon as we think of it (Savulescu and Persson 2012). It deserves emphasis that the god mentioned

in its name is not God from Judeo-Christian and Islamic religious traditions.

In these, God leaves our freedom intact. We are free both to do good and to sin. Our “freedom to fall” is thus preserved. Savulescu and Persson’s “god

machine,” conversely, is a device that intervenes as soon as we develop a

morally unacceptable thought and wish to behave in line with it. Its aim is

nothing less than enhancing the role of God from the mentioned religious

traditions. Disabling us to act as we wish by policing our thoughts, such a

device is rather a “police machine” than a “god machine.”

2.

It

is also a matter of debate who should be in charge of developing and

controlling this device. Even if a democratically elected government were

mandated with the task, its arbitration would have to be both repressive and

politically legitimate: repressive because it would forcefully intervene

whenever we decided to act in a way that it considered morally unacceptable,

politically legitimate because it would be developed and monitored on the basis

of decisions being made in the realm of politics. The very fact that these

decisions would prescribe what we are allowed to will, implies that the “god

machine” has illiberal underpinnings – even if those who control it might

be democratically elected. Moreover, as it intervenes by changing what we think

to do, it can be argued that the“god machine” is

detrimental to our very freedom of thought.

3.

In

Unfit for the Future, Persson and Savulescu adopt a

critical attitude toward liberalism in order to justify a role for the state in

mandating moral bioenhancement aimed at helping

humanity avoid ultimate harm (Persson and Savulescu 2012, 42–46). Abandoning liberalism and

accepting a form of authoritarianism, even an enlightened one, is however a

step back in humanity’s historical development. Authoritarian and totalitarian

states employ political repression to eliminate those who disagree with their

ideologies. Using political repression is, in short, what such states do.

It is undoubtedly

possible to argue in favor of political repression

and totalitarianism, especially if the repressive authority is a morally

enlightened one. But at least let it be noted, as a matter of fact, that

compulsory moral bioenhancement is not a liberal concept. In the worst

case, it can be repressive. Political repression

and totalitarian, or another form of authoritarian, rule is a stage in

humanity’s historical development that appears to have been left behind in most

of the developed world. More than anything else, historical totalitarianism has

left bloody stains of extreme evil on the history of humanity, and it should be

noted and emphasized, time and again, that builders of totalitarian systems

have never come close to fulfilling their rhetorical promises of “freedom from

oppression,” “living space,” “heaven on earth,” and others conveyed in

phantasmal slogans.7 With the passage of time, reality under

totalitarian rule deviates more and more from

the proclaimed goals, rather than converging toward them.

Creating morally enhanced

post-persons

Insofar as we

have progressed in formulating and adhering to more and more expansive and

inclusive human rights, we are bound to condemn totalitarian theory and

practice as regressive and immoral. But even if we should assign higher value

to life strictly regulated in the totalitarian sense than to no life at all, it

is exactly the repugnant nature of this choice that should prompt us to

investigate any possible alternative to the dilemma. As argued above, we are

actually facing a trilemma, not a dilemma, and

therefore ought to concentrate on the third alternative, which is neither

extinction nor totalitarianism.

We propose the

creation of morally enhanced post-persons as this third alternative. The

following conceptual clarifications related to the notion of morally enhanced

post-persons are relevant for our argument:

1.

Post-persons

differ from “mere persons” in that they have a higher moral status.

2.

“Mere

persons” are currently existing humans (with the

proviso that some currently existing humans do not satisfy the criteria for

personhood).

3.

Moral

status enhancement is the improvement of a being’s moral entitlement to

benefits and protection against harms.

4.

Moral

enhancement is the improvement of the moral value of an agent’s actions or

character. It is moral disposition enhancement.

5.

In

our understanding, higher moral status implies not only cognitive superiority,

but superior moral dispositions as well, i.e. a higher moral value of an

agent’s actions or character.

The most

important component in our understanding of post-persons is that their higher

moral status vis-ą-vis mere persons

entails not only cognitive supremacy, but also their superior moral outlooks and inclination to act in line with them.

The gap between what we do and what we believe we ought to do might well be the greatest predicament of human moral

existence (see Rakić 2014, 248). Humans have the

disposition to be capable of autonomous practical reasoning, and moral

reasoning in particular. But if someone is in certain cases unwilling to act in

accordance with what she knows is right, she is in such cases incapable of

moral action. Wouldn’t a being that is always behaving in line with what she

believes to be moral be someone with a higher moral status than the one we

have? Wouldn’t that be a post-person? We argue that it would, because the

difference between beings who are capable of moral reasoning only and those who

practice their moral beliefs is a qualitative difference amounting to a

differentiation in moral status (for an elaborated version of the above

sketched argument, see Rakić 2015, 60–61).

In the February

2013 issue of the Journal of Medical

Ethics, Nicholas Agar published a paper on the possibility/imaginability and moral justifiability of the creation of

post-persons. Agar’s position was one that advocated an inductive argument against the justifiability of their

creation. Agar believes, specifically, that the creation of post-persons is too

risky, as they might sacrifice or in other ways harm mere persons. It is

morally permissible to sacrifice objects with no moral status in the interest

of sentient nonpersons (e.g., to use carrots for feeding rabbits). It is also

morally permitted to sacrifice/harm sentient non-persons for the benefit of

human persons (e.g., experiments on rhesus monkeys in order to find better

treatments for diseases affecting humans). These permissions provide inductive

support for a moral justification for sacrificing mere persons for the sake of

post-persons. Hence, we should avoid creating post-persons (Agar 2013).8

Arguing against

Agar, we will present another inductive argument and, on top of that, offer a

deductive argument favoring the creation of post-persons. Both

arguments presuppose that the higher moral status of post-persons implies not

only their enhanced cognitive abilities, but also their enhanced morality. For enhanced

morality we do not require only a superior understanding of moral issues (which

is a cognitive quality), but also our motivation to behave in line with this understanding.

Inductive

argument favoring the eventuation of morally bioenhanced post-persons

If a higher moral status of post-persons implies an

enhanced morality, morally bioenhanced post-persons

will not be inclined to annihilate or severely harm mere persons, because they

will presumably consider it their moral duty not to cause detriment to the

beings who enabled them to come into existence. If

mere persons have moral inhibitions against annihilating species of moral

status lower than their own, it is even less likely that morally enhanced

post-persons will annihilate mere persons.

Deductive

argument favoring the eventuation of morally bioenhanced post-persons

Even if morally bioenhanced

post-persons believed that it was morally justified to obliterate mere persons,

such a standpoint would by necessity be morally superior to the wish of mere

persons (i.e. morally unenhanced persons) to continue to exist. This deduction

can be derived from the following two premises:

1.

Morally

enhanced persons make better moral judgments than mere persons.

2.

One

of the attributes of post-persons, as we defined them, is that they are morally

enhanced.

From these two true statements we can deduce a third

that is also true:

3.

Post-persons

make better moral judgments than mere persons.

The third statement in this syllogism further implies

that we have a moral duty to accept what post-persons consider to be morally

preferable. Consequently, as it is our moral duty to help establish a more

moral world than the currently existing one, the creation of morally bioenhanced post-persons is not only morally justified, but

our moral duty as well.9

All in all,

morally bioenhanced post-persons are morally

desirable: they might have the potential to confront the danger of extinction

of humanity or a milder form of existential harm, they are unlikely to

seriously jeopardize mere persons, and even if they did, they would be morally

justified in doing so. Hence, we have a moral duty to embark on the path of

either creating morally bioenhanced post-persons de novo or morally upgrading mere

persons to the status of morally bioenhanced

post-personhood. In either case, and in stark contrast to some bioconservatives who tend to misrepresent the entire

project of human enhancement as threatening to humanity, a corollary of our

argument is that the real threats to the existence and well-being of our

species – existential risks – constitute a major motivation in favor of undertaking

human bioenhancement, moral bioenhancement

included.

Conclusions

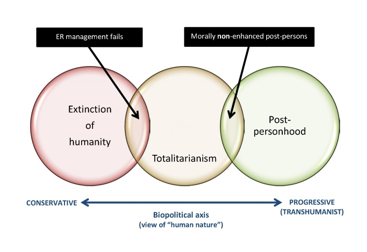

The trilemma

The

essential trilemma is encompassed in a simplified

form in Figure 1. Possible future evolutionary trajectories seem to tend into

three broad regions (or “attractors” in a loose sense). Extinction is,

unfortunately, the prospect that will remain with us for a long time to come,

since it is highly unlikely that the double trend toward both more dangerous,

and destructive, weapons of mass destruction and larger, more destructive,

perturbations inflicted by human civilization on our planetary environment will

reverse soon.

One way we can

try to avoid extinction is via totalitarian rule that will punish any attempt

of humanity to inflict existential harm upon itself. Another way is to embark

on the path of moral bioenhancement. This type of

enhancement can be compulsory or voluntary. We have shown why compulsory moral bioenhancement is potentially repressive in nature. Hence,

it belongs to the grey area between totalitarian rule

and morally enhanced post-personhood.

A solution

Totalitarianism

in its traditional form has been surpassed in the developed world.

Post-personhood, however, contains a totalitarian element if it is based on the

type of compulsory moral bioenhancement that has been

referred to in this article. Both traditional totalitarianism and this type of

compulsory moral bioenhancement deprive humans of

their freedom, which is a key component of their human existence. Hence, they

not only contain a totalitarian element, but also inflict a degree of

existential (possibly ultimate) harm on humans. In actual fact, the two left

circles of Figure 1, i.e. extinction of humanity and totalitarianism (including

the two grey areas) include the infliction of existential (possibly utimate) harm as an important similarity. They differ in

the degree of harm they inflict: the harm of totalitarianism is less dramatic

than the harm of humanity’s extinction.

Figure 1. A schematic representation of three attractors in

the space of futures. The biopolitical

axis is described in detail by Hughes (2004). Part of the entire domain

of post-personhood on the right which does not overlap with

totalitarianism corresponds to morally enhanced post-personhood (its

complement, obviously, corresponds to morally non-enhanced post-persons, as labeled).

The obnoxious

nature of these choices, however, leaves us with one reasonable option only: to

try to continue our human existence in a morally bioenhanced

form, which implies that we have not been coerced into such an existence, but

have voluntarily opted for it. We argue, therefore, that voluntary moral bioenhancement is an essential strategy to follow in order

to achieve morally enhanced post-personhood. And morally bioenhanced

post-personhood is the best option we have in order to avoid extinction,

totalitarianism, or any other form of existential harm.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish

to acknowledge very useful comments of Russell Blackford which immensely

improved a previous version of the manuscript. The authors have

been partially supported through projects ON 176021 and III41004 of the Ministry of Education, Science and

Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia

Notes

1. Persson and Savulescu

define ultimate harm as an event or series of events that make worthwhile life

on this planet forever impossible (Persson and Savulescu 2014, 251); thus, it is equivalent to the adverse

outcome of some existential risks. The fine points of difference between the

two concepts are irrelevant for the purposes of the present study.

2. In the words of Persson

and Savulescu: “If safe moral enhancements are ever

developed, there are strong reasons to believe that their use should be

obligatory, like education or fluoride in the water, since those who should

take them are least likely to be inclined to use them. That is, safe, effective

moral enhancement would be compulsory” (Persson and Savulescu 2008, 174). It ought to be noted, however, that

in their more recent writings, Persson and Savulescu don’t take a decisive position on the issue of

whether moral bioenhancement ought to be compulsory

(e.g., Persson and Savulescu

2012).

3. Compare

Kahane 2013.

4. Contrary to our untutored intuition, this

does apply even to ongoing processes like climate change and nuclear

proliferation, since they retain the capacity to do immense harm on temporal

horizons much longer than the timescales for bioenhancement

of any kind.

5. This does not mean that our stance is

that humanity has no reasons other than diminishing existential risks to embark

on the path of moral bioenhancement. It also does not

imply that moral bioenhancement guarantees that we will avoid threats to our existence. We assert

only that moral bioenhancement might significantly

lower the likelihood of such threats becoming reality.

6. Even pure

research on the long-term phenomena is usually severely hampered by the lack of

such vision in funding agencies and donors. Management and mitigation are bound

to face much more formidable obstacles of that kind.

7. NB: we don’t argue that the mere fact

that a society has one or more illiberal laws implies that it is totalitarian.

Certain illiberal laws can be found in democratic states as well. Our argument

is that the notion of compulsory moral bioenhancement

contains the danger of regression into totalitarianism, especially if it is

accompanied by the concept of a “god machine” policing our thoughts. For

related arguments, see the “hellish”

scenarios in Bostrom (2013) or the argument that compulsory moral

bioenhancement can already inflict existential harm upon humans by divesting

them of what we used to call “free will”– even though

it is supposed to lower the likelihood of such harm (Rakić 2014). Another

important point is that we need to take a long-term

perspective: if a mechanism of repression persists, even if it is not used

in practice on short timescales, the probability that it will be used with

disastrous consequences just grows with time. While it is certainly possible to

conceive of conditions under which compulsory bioenhancement would not be drastically

different from compulsory schooling (e.g., Blackford 2014, 44–49), it is

an entirely different issue whether such special conditions are likely at any

particular point in the future.

8. Agar’s article sparked various reactions,

both supportive and critical. The standpoints of the authors who commented on

Agar’s position in the JME issue in

question can be classified as follows: post-persons are imaginable, but

undesirable (Sparrow 2013); the eventuation of post-persons is unlikely, but

not undesirable (Hauskeller 2013); post-persons are

both imaginable and desirable (Persson 2013 and

Douglas 2013).

9. For a more extensive argument, see Rakić

(2015).

References

Agar

N. 2013. Why is it possible to enhance moral status and why

doing so is wrong? Journal of Medical Ethics 39:

67–74.

Ahrens, T.J., and A.W. Harris. 1992. Deflection and fragmentation of

near-Earth asteroids. Nature 360: 429–33.

Atlas, R.M. 2002. Bioterrorism: From threat to reality.

Annual Review of Microbiology 56: 167–85.

Baum, S.D. 2010. Is humanity doomed?

Insights from astrobiology. Sustainability 2: 591–603.

Blackford, R. 2014. Humanity enhanced: Genetic choice and the

challenge for liberal democracies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bostrom, N. 2002.

Existential risks: Analyzing human extinction scenarios

and related hazards. Journal of Evolution and Technology 9(1).

Available at http://www.jetpress.org/volume9/risks.pdf (accessed September 6, 2016).

Bostrom, N. 2003.

Astronomical waste: The opportunity cost of delayed technological development. Utilitas 5: 308–314.

Bostrom, N. 2013. Existential risk prevention as global priority. Global Policy 4: 15–31.

Bostrom, N., and M.M. Ćirković, ed. 2008. Global catastrophic risks.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brin, D.

1998. The transparent society: Will

technology force us to choose between privacy and freedom? New York: Perseus

Books.

Caplan, B. 2008. The totalitarian threat. In Global catastrophic risks, ed. N. Bostrom and M.M. Ćirković,

498–513. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ćirković, M.M.

2004. Forecast for the next eon: Applied cosmology and the long-term

fate of intelligent beings. Foundations of Physics 34: 239–61.

Cockell, C.S.

2008. An essay on extraterrestrial liberty.

Journal of the British

Interplanetary Society 61: 255–75.

Douglas,

T. 2013. The harms of status enhancement could be compensated

or outweighed: A response to Agar. Journal of Medical Ethics 39: 75–76.

Harris, J. 2011. Moral enhancement

and freedom. Bioethics 25: 102–111 .

Hauskeller, M. 2013. The moral status of post-persons. Journal of Medical Ethics 39: 76–77.

Hughes, J. 2004. Citizen cyborg: Why democratic societies must

respond to the redesigned human of the future. New York: Basic Books.

Jansen, H.J., F.J. Breeveld,

C. Stijnis, and M.P. Grobusch.

2014. Biological warfare, bioterrorism, and biocrime.

Clinical Microbiology and Infection 20: 488–96.

Kahane, G. 2013. Our cosmic insignificance. Nous 48: 742–72.

Matheny, J.G.

2007. Reducing the risk of human extinction. Risk Analysis 27: 1335–1344.

Parfit, D. 1984. Reasons and persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Persson, I.

2012. Is Agar biased against “post-persons”?

Journal of Medical Ethics 39:

77–78.

Persson, I.,

and J. Savulescu. 2008. The perils of cognitive enhancement

and the urgent imperative to enhance the moral character of humanity. Journal of Applied

Philosophy 25: 162–77.

Persson, I.,

and J. Savulescu. 2012. Unfit for the future: The need for moral enhancement. Oxford:

Oxford Univerity Press.

Persson, I.,

and J. Savulescu. 2014. Should moral bioenhancement be compulsory? Reply to Vojin

Rakic. Journal of Medical Ethics 40: 251–52.

Rakić, V. 2014. Voluntary moral enhancement and the survival-at-any-cost bias.

Journal of Medical

Ethics 40: 246–50.

Rakić, V. 2015. We

must create beings with moral standing superior to our own. Cambridge Quarterly of Health Care Ethics

24: 58–65.

Savulescu, J.,

and Persson, I. 2012. Moral enhancement,

freedom, and the god machine. The Monist 95:

399–421.

Sparrow,

R. 2013. The perils of post-persons. Journal of Medical Ethics

39: 80–81.