|

A

peer-reviewed electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and ISSN

1541-0099 26(2)

– July 2016 |

The Concept of the Posthuman: Chain of

Being

or Conceptual Saltus?

Daryl J.

Wennemann

Fontbonne

University

dwennemann@fontbonne.edu

Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 26 Issue 2 – July 2016 - pgs 16-30

To the wise man, nothing is foreign or impassable.

Antisthenes1

There

are many divers ways and modes of

surpassing:

see thou thereto! But only a

buffoon

thinks: “man can also be overleapt.”

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche2

Abstract

A central task in

understanding the theme of the posthuman involves relating it to the concept of

the human. For some, there is continuity between the concepts of the human and

the posthuman. This approach can be understood in the tradition of the great

chain of being. Another

approach posits a conceptual, and perhaps ontological, saltus (μετάβασις

εἰς ἄλλο γένος).

Here, the concept of the posthuman is taken to represent a radical departure

from the realm of the human. After considering Lovejoy’s scheme of the great

chain of being, Aristotle’s view of a conceptual saltus

(μετάβασις εἰς ἄλλο

γένος), and their historical significance, I will

suggest how we might distinguish various concepts of the posthuman from the

human by applying Rudolf Carnap’s approach to defining multiple concepts of

space. We can thus create a linguistic convention that will assist in

constructing useful conceptions of the human and posthuman – these can

clarify the prospects of a posthuman future.

Introduction

The theme of the posthuman is gaining

significant traction in the disciplines of anthropology, cultural studies,

literary theory, and philosophy. But how are we to conceive of the posthuman? Kevin LaGrandeur has remarked that the meaning of the

terms “posthuman” and “transhuman” are ambiguous. “As post- and transhumanism have become

ever-hotter topics over the past decade or so, their boundaries have become

muddled by misappropriations and misunderstandings of what defines them, and

especially what distinguishes them from each other” (2015, 49). According

to one conception, the meaning of the term “post” in this context implies some

continuity between the human and the posthuman, since it is only in relation to

the human that we refer to the posthuman. Another approach posits a radical

hiatus between the human and the posthuman, supposedly indicated by the prefix

“post.” I will explore these two approaches to the posthuman by applying the

traditional great chain of being conception of reality and the notion of a

saltus, or conceptual leap, that can be traced to Aristotle’s concern with μετάβασις

in order to disambiguate differing meanings of the term “post” and so gain some

purchase on the theme of posthumanity. As we shall see, Kant’s reflections on

the self-conflicting interests of reason, expressed in the laws of homogeneity

and specification, may be applied to contemporary theorizing about the

posthuman:

This twofold

interest manifests itself also among students of nature in the diversity of

their ways of thinking. Those who are more especially speculative are, we may

almost say, hostile to heterogeneity, and are always on the watch for the unity

of the genus; those, on the other hand, who are more especially empirical, are

constantly endeavoring to differentiate nature in such manifold fashion as

almost to extinguish the hope of ever being able to determine its appearances

in accord with universal principles. (Kant 1965, 540, A 655/B683)3

The interest in homogeneity underlies the great chain of

being approach to the concept of the posthuman and the interest in

specification motivates the conceptual saltus approach.

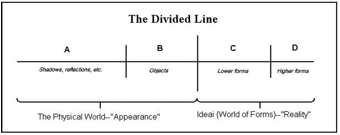

The great chain of being

The idea of a great chain of being has

been a dominant motif in the Western philosophical tradition. Arthur O. Lovejoy

traced the idea to the philosophy of Plato. The divided line analogy in Plato’s

philosophy appears in The Republic (509d–510a). It posits a continuity between various

grades of being. The proportion represented on the divided line provides for

grades of intelligibility running throughout and across the different grades of

being, from images and physical entities of the visible world of becoming

(represented by sections A–B of the table below), to mathematical

ideas and the forms of various kinds of beings and the virtues. The latter

comprise the intelligible world of being (represented by sections C–D of the table):

Such a conception of reality does not

allow gaps from one kind or grade of being to another. The philosophical roots

of this conception reach back to the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides. For

Parmenides, non-being is not something real and cannot be thought without

contradiction, since we can think of non-being only in terms of being. This

insight informed the chain of being conception of reality that Plato developed,

such that there must be a continuity in the transition from one kind of being

to another. Within this philosophical tradition, therefore, nature abhors an

ontological vacuum. According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica (2015),

The term [chain of being] denotes three general features of

the universe: plenitude, continuity, and gradation. The principle of plenitude

states that the universe is “full,” exhibiting the maximal diversity of kinds

of existences; everything possible (i.e., not self-contradictory) is actual. The

principle of continuity asserts that the universe is composed of an infinite

series of forms, each of which shares with its neighbour at least one

attribute. According to the principle of linear gradation, this series ranges

in hierarchical order from the barest type of existence to the ens perfectissimum, or God.

This view of reality can be seen in the

conviction of modern physicists that there must exist elements on the periodic

table where there appears to be a gap. It can also be glimpsed in the scala

naturae conception of Darwinian evolution whereby there must not be missing

links in the development of species. Lovejoy opined in 1936 that the concept of

the great chain of being had informed not only philosophy but science and

poetry. And yet, he found it to be unfamiliar to many, including some

well-educated persons:

The

title of this book [The Great Chain of Being], I find, seems to some not

unlearned persons odd, and its subject unfamiliar. Yet the phrase which I have

taken for the title was long one of the most famous in the vocabulary of

Occidental philosophy, science, and reflective poetry; and the conception which

in modern times came to be expressed by this or similar phrases has been one of

the half-dozen most potent and persistent presuppositions in Western thought.

It was, in fact, until not much more than a century ago, probably the most

widely familiar conception of the general scheme of things, of the

constitutive pattern of the universe; and as such it necessarily predetermined

current ideas on many other matters. (Lovejoy 1965, viii; italics in the

original)

Now, I believe that the traditional

idea of the great chain of being can contribute to our understanding of some

conceptions of the posthuman. From this perspective, the posthuman is

understood in relation to the human. Even if there is a radical departure from

the human, according to this scheme, there is still continuity in development

from one kind to the other. There are several examples of this kind of

development that can be seen in the literature to date on the concept of the posthuman.

First, we have the attempt to emulate

human cognition through the scanning of the human brain and the development of

neural models (Sandberg and Bostrom 2008). Here there is a continuity in the

functioning of the brain and a computer simulation. Human cognition is given a

new non-biological platform for its functioning. The increase in the speed of

computerized cognition would make for a posthuman being but the model of

cognition would remain human.

Another approach to the posthuman, one considered

by Francis Fukuyama in Our Posthuman Future (2000), involves the genetic

modification of human beings. Again, while there may be a break between the

human and the posthuman, there is also discernible continuity inasmuch as we

can identify the new posthuman being over against the human.

There is yet another approach to the

posthuman that seems to combine a break and a continuity with the human. Chris

Hables Gray’s work Cyborg Citizen explores the ways in which our own

cyborgization can allow us to shape our subjectivity. It is interesting, in

this context, that Gray distinguishes between cyborgs and “pure humans” (Gray 2002, 131). He notes that cyborgs are proliferating and redefining

many of the most basic political concepts of human existence (2002, 19) and

that new cyborg citizens must find ways to protect their rights (2002, 29). He

also notes that our only choice is to proliferate human and posthuman

possibilities. In the end, he believes we will be able to live longer and better

than ever before, pushing “the species into new, enlightening adventures in

inner and outer spaces” (2002, 201). This conception of the posthuman seems to

rely upon a continuity in the movement from the human to the posthuman. It is

as if every possible niche in the spectrum of our self-cyborgization must be

filled. The human imagination spins possible worlds, and contemporary

technoscience fills the void between the possible and the actual:

At

the core of this web are the cyborg technosciences, which are extremely

evocative technologies – evocative not just in terms of what they provoke

from us as individuals, but especially in what possible futures they might

evoke for our culture as a whole. Dreaming of possible constructions of the

impossible leads to real transformations, new types of life, changes in the

very way we think of space, time, erotics, art, artificiality, perfection, and

life, ourselves. Technoscience is constantly deconstructing the idea of the

impossible. (2002, 194)

A central issue in the posthuman age,

in my view, is whether our imaginations might have a disciplining function

rather than leaving us in what SŅren

Kierkegaard called “the despair of possibility.” In this regard, Arjun

Appadurai has noted as follows:

In

fact, it may be more useful to see design as trying to regulate fashion by

slowing down the infinite play of combinatorial possibilities, the dizzying

vista of new arrangements of bodies, materials, forms, and functions that

advertising daily puts before us.

And

this might lead us closer to the logic of connecting design and context than

the conventional idea that design, being the loyal servant of fashion, simply

adds technique to the lust for change that defines fashion. Design certainly

involves the imagination, but it is defined by the imagination as a source of

discipline and not imagination merely as a source of new possibilities for

combination and cohabitation among objects. (Appadurai 2013, 263)

The great chain of being approach to

the posthuman may be seen as registering a revolt against the eclipse of the

human by the posthuman. From this perspective, posthuman beings represent a

loss of humanity even when, and perhaps because, there is a leap in the power

available to enhanced human beings. An increase in the quantity of power at our

disposal results in a decrease in the qualitative character of human existence.

Arthur Kroker expresses this concern in his Exits to the Posthuman Future:

If

it is the case that the sheer force of technological innovation quickly pushes

traditional conceptions of humanism aside to make way for all the emerging

signs of the posthuman – drift culture, recombinant technology,

figural aesthetics, distributive consciousness –

then it is true that something indispensably human, whether articulated by

conscious political protest, mobilized by social unrest, or motivated by the

persistence of human memory itself, remains as the phantasmagorical essence of

the future of technological posthumanism. (Kroker 2014, 4)

Kroker sees the posthuman future as

undermining all of the previous “human” markers including a unitary

species-logic, private subjectivity, and hierarchical knowledge. This latter

marker posits human beings as “the universal value-standard of all events”

(Kroker 2014, 5). If there is a leap from the human to the posthuman, the great

chain of being mentality senses a continuity within the gap even if it is only

the presence of an absence. And so, Kroker argues that the technological

society is motivated by the return of the repressed. The shadow of the human

haunts the posthuman as a loss.

The

leap into the posthuman future

In contradistinction to the motif of

the great chain of being, we may posit that of a leap into the posthuman

future. Perhaps it is because Western thought has typically conceived of

reality as a great chain of being that the notion of a leap from one kind to

another has historically been seen as ontologically anomalous and logically

illicit. Aristotle identified a flaw in our reasoning that involves making a

discontinuous conceptual leap from one kind or genus to another, a metabasis

eis allo genos (μετάβασις

εἰς ἄλλο γένος).

Such a saltus renders a demonstration invalid and unscientific by introducing

ambiguity into the meaning of the terms we use in an argument.

John K. O’Connor notes that such a flawed

demonstration is not just a matter of an invalid syllogism: “[A]lthough it is

possible to shift from one genus into another in the course of a syllogism

without affecting the formal evaluation of the syllogism, such a transition

generally prevents the syllogism from rising to the level of science” (O’Connor

2008, 739). The reason for this lies in Aristotle’s conception of a science.

Since every science is defined by a genus of being with which it is concerned,

to leap from one genus to another is to cross a scientific boundary.

Admittedly, it is possible for a science to borrow from a higher genus, as when

optics borrows from geometry (O’Connor 2008, 742, n. 19). But, in general,

Aristotle was concerned with maintaining scientific boundaries. This required

that a scientific demonstration remain exclusively within a single genus of

being. Hence, for Aristotle, each science was defined by, and tied to, the

genus of its subject matter. For a demonstration to fail to remain within a

single genus is for it to commit a metabasis

eis allo genos. In moving from one genus to another the chain of essential

relations is broken, resulting in a failure to demonstrate the conclusion

(O’Connor 2008, 741).

If we glance forward to the philosophy

of Immanuel Kant, we can see that he was keenly aware of the character of the

transitions (Übergang) in his thought. The Groundwork is divided

according to three transitions. The first is a transition from common rational

to philosophical moral cognition (4:393)4. The second is the

transition from popular moral philosophy to metaphysics of morals (4:406). The

third is a transition from metaphysics of morals to the critique of pure

practical reason (4:446). Kant’s Metaphysical Foundations of Physical

Science may also be seen as providing a transition from the general

metaphysics of nature to a special metaphysics of nature (Plaass 1994, x, xi).

And at the time of his death, Kant left unfinished a work titled Transition

from the Metaphysical Foundations to Physics (Plaass 1994, 48–49).5

A significant part of Kant’s critique

of traditional metaphysics involved pointing to illegitimate leaps in thought.

And so, metabasis had a significant role in his epistemology. Kant

recognized that human reason tends to pose questions that we cannot answer. It

also has a tendency to go beyond its own limits in seeking the ultimate basis

of our experience. For example, in the thesis of the fourth antinomy concerning

the cosmological proof for the existence of God, Kant noted that some thinkers

have taken the liberty of making a conceptual leap (metabasis eis allo genos), moving from the existence of

contingent empirical objects to the existence of a necessary being, which he

judged to be an illegitimate saltus (Kant 1965, 419, A 461/B 489). Again, in

the Religion, Kant argued that it is

a mistake to transform a schematism of analogy into one of object-determination:

“But between the relationship of a schema to its concept and the relationship

of this very schema of the concept to the thing itself there is no analogy, but

a formidable leap (μετάβασις

εἰς ἄλλο γένος)

which leads straight into anthropomorphism” (Kant 1996, 107, 6: 65, note).

Finally, Kant argued that there is a law of homogeneity that is posited by

reason as a heuristic device that makes our experience possible. Accordingly,

“all differences of species border upon one another, admitting of no transition

from one to another per saltum, but

only through all the smaller degrees of difference that mediate between them” (Kant

1965, 543, A 659/B 687; italics in the original).

O’Connor argues that the conception of

an “incidental, argument-level metabasis” can easily be extended to

“systemic foundational metabasis” (2008, 742, italics in the original). He

finds that this was the course of development that informed the philosophy of

Franz Brentano and then Edmund Husserl. Brentano’s concern was to differentiate

the scientific boundaries of psychology and physiology. This may have been a

basis for Husserl’s later distinction between transcendental phenomenology and

descriptive psychology (cf., O’Connor 2008, 743). Brentano was also concerned

to avoid equivocation and he considered metabasis to be a source of

equivocation (2008, 743).

Can a leap across a chasm from one kind

to another be legitimate? According to Louis P. Pojman, Kierkegaard conceived

of freedom as a leap beyond the realm of natural determination:

In the last

analysis freedom as voluntary choice happens in the eternal “Now” which breaks

into the normal course of determined action. It is a metabasis eis allo genos (something of an altogether other dimension

from ordinary events), a mystery which signals divine grace and omnipotence.

(Pojman 1990, 49)6

Here, in its most profound significance,

the metabasis eis allo genos

implicated in human freedom is not a mere conceptual inference but may bring

about a transition from one stage of life to another.

It may be that the transition from the

human to the posthuman is a leap of faith of a sort. For those who have faith

in the progressive character of technology, the movement to the posthuman holds

forth the possibility of an advance and improvement over against the human.

Kevin LaGrandeur notes, in this regard, that a posthuman condition is one to

which transhumanists aspire. Various technological developments may be seen in

this context as bringing about a qualitative leap from one kind to another. The

posthuman can thus be understood in terms of a metabasis eis allo genos:

Basically,

transhumanists believe in improving the human species by using any and every

form of emerging technology. Technology is meant in the broad sense here: it

includes everything from pharmaceuticals to digital technology, genetic

modification to nanotechnology. The posthuman is the state that transhumans

aspire to: a state in which our species is both morally and physically improved,

and maybe immortal – a species improved to the point where we perhaps

become a different (and thus “posthuman”) species altogether. (LaGrandeur 2015,

49)

The approach to the posthuman that is

conceived in terms of an ontological leap from the human to the posthuman seems

to have as its strategy to recognize the ontological gap between diverse kinds

of things without falling into the trap of anthropomorphism. The interest of

reason expressed in the law of specification motivates this approach. It is remarkable

that the kind of insight involved in recognizing the posthuman as requiring a

cognitive leap to a new kind of being that is discontinuous with the human

would seem to require a peculiarly human form of cognition. According to Jeremy

Campbell,

Computers are

good at swift, accurate computation and at storing great masses of information.

The brain, on the other hand, is not as efficient a number cruncher and its

memory is often highly fallible; a basic inexactness is built into its design.

The brain’s strong point is its flexibility. It is unsurpassed at making shrewd

guesses and at grasping the total meaning of information presented to it.

(Campbell 1982, 190)

Such cognitive leaps may be a

distinguishing mark of the human over against the posthuman, unless and until

posthuman beings become capable of it.

But then, from the perspective of a

transcendental posthumanism, the difficulty arises as to whether a radically

alien posthuman being could be cognized. Could we recognize a posthuman person

as a person if the character of its existence lay outside and beyond any

categories of personhood available to us? Does such an approach exhibit a

fascination with the strange, the alien, that which is foreign and unknown?

There is a human need for mystery that this approach might satisfy. But, then

again, the strangeness of this approach might just indicate that we are on the

right track in our attempt to comprehend the posthuman. Jeremy Campbell notes

that in one of Dorothy L. Sayers’ novels, the character Lord Peter Whimsey

finds that the reason for a certain satisfaction in some new evidence in a

murder he is investigating

is that it adds

the final touch of utter and impenetrable obscurity to the problem which the

inspector and I have undertaken to solve. It reduces it to the complete

quintessence of incomprehensible nonsense. Therefore, by the second law of

thermo-dynamics, which lays down that we are hourly and momently progressing to

a state of more and more randomness, we receive positive assurance that we are

moving happily and securely in the right direction. (Sayers 1932, 236; cited in

Campbell 1982, 52)

If, in his treatment of the human, Albert

Camus found it necessary to focus on the strangeness of existence (Camus 1993),

perhaps it is to be expected that the development of a posthuman existence

would be strange to us. Camus held that human

existence is absurd since we live in a world that does not meet our needs.

Rebellion is a response to this condition that expresses “hope for a new

creation. Man is the only creature who refuses to be what he is. The problem is

to know whether this refusal can only lead to the destruction of himself and of

others…” (Camus 1993, 11). Part of the challenge of the movement toward the

posthuman, from the perspective of Camus’ philosophy, is whether this new creation

will overcome the absurdity of existence or whether the refusal to be ourselves

will lead to our self-destruction. Or, will posthuman beings not feel the need

to rebel?

In Posthuman

Life, David Roden provides an account of the posthuman that seems to break

the bounds of sense in that it attempts to conceive of an utterly alien being

that lies beyond our ability to cognize. Roden posits a sort of ontological

rupture that he designates as a “disconnection” from the human in order to give

the prefix “post” its most fundamental meaning (Roden 2015, 8 et passim).

According to his conception, a breach in continuity between the human and the

posthuman is necessary to adequately grasp the posthuman. But it is not a

difference between kinds of being, in his view, but a difference between

individuals. Still, a philosophical consideration of the posthuman would thus

seem to require a metabasis.

Interestingly, the Greek term “genos” (γένος)

can have the meaning “offspring,

even a single descendant, a child”

(Liddell and Scott 1889). And so, Roden’s account may be said to involve

a metabasis eis allo genos,

if the image of the posthuman as the offspring of the human does not imply too

close a tie between them. Since a leap must be from somewhere to a place beyond

a gap, we can see Roden’s leap to the posthuman as proceeding from the human.

Roden acknowledges this in a recent interview: “This being said, I acknowledge

that my characterization of the posthuman is human-relative. The disconnection

thesis describes the posthuman in terms of the capacity of posthumans cut free

from the Wide Human” (Bakker 2015, 167).

Carnapian construction

In a previous work, Posthuman Personhood (2013), I introduced a linguistic convention

in order to disambiguate different meanings of the term “human.” Following the

lead of Rudolf Carnap, I used superscripts to designate biological humanity

with the term “humanB” and moral humanity with the term “humanM”.

The term “humanM” refers to the class of persons (in the moral

sense), as opposed to genetically human beings or humansB. Note

again LaGrandeur’s distinction between these two dimensions of the human, “The

posthuman is the state that transhumans aspire to: a state in which our species

is both morally and physically improved…” (LaGrandeur 2015, 49). We should

consider the possibility that our species could be physically “improved” but

not morally improved. It may also be possible that the species could be morally

improved without being physically improved.

In a more recent work, “Posthumanisms: A

Carnapian Experiment” (2015), I sought to disambiguate the term “post” so as to

distinguish different senses of the term “posthuman.” We can thus conceptualize

a hypo posthumanism and a hyper posthumanism, designated by the terms “postohumanB” and “postRhumanB”

respectively.9

Carnap

held that our received folk language is so shot through with ambiguity that it

must be altered to render it amenable for philosophical work. He promoted a

principle of tolerance that allows for each of us to create our own language in

order to clearly express our thought. What he considered imperative was that each

person specify just what language s/he uses. Consider Carnap’s treatment of the

concept of space. In Carnap’s

Construction of the World: The Aufbau and the Emergence of Logical Empiricism,

Alan W. Richardson substitutes the English term “space” for the German term “raum.” Richardson explains that Carnap

recognized a distinction between formal space, designated by the letter S, intuitive space, designated by the term

S′, and physical space, designated by S′′. He further

recognized a distinction between topological, projective, and metrical space,

designated by the letters t, p, and m, respectively. Each of these could have a

dimensional variant designated by numbers or the letter n: “Thus, for example,

S′4t designates four-dimensional topological intuitive space, and Snp

designates projective formal space of arbitrarily many dimensions” (Richardson

1998, 141). Part of Carnap’s argument was that philosophical disputes over the

concept of space could generally be resolved by using terms that distinguish

these different concepts. It is plain that to simply speak of space would be

impossibly ambiguous.

Likewise, disputes over the character of

the posthuman may be traced to the diverse meanings given to the term

“posthuman.” The possibility of adequately conceptualizing the posthuman is

hopeless if the term is used with divergent meanings so that readers seeing it

have widely divergent ideas of what is being discussed. John Locke made a

similar observation in An Essay

Concerning Human Understanding (1689): “The chief End of Language in

Communication being to be understood, Words serve not well for that end,

neither in civil, nor in philosophical Discourse, when any Word does not excite

in the Hearer, the same Idea which it stands for in the Mind of the Speaker”

(Locke 1975, bk III, ch. 4. IX, ļ 4, 476–77).

My hope is that my terminological

conventions might clarify some of the ambiguity surrounding the use of the term

“posthuman,” whether it is conceived according to the model of the great chain

of being or a conceptual saltus. The central Carnapian insight here is that

disambiguating the term “posthuman” can clarify philosophical disputes

surrounding the issue of the posthuman. It also serves to illustrate that the

area of the posthuman is not a unified field of study. There are, rather,

diverse approaches. Some scholars seek a continuity of the human and posthuman

in order to maintain a grasp on the posthuman reality. Others see a rupture

with the human, posing both a thrilling possibility and a threat.

For some,

including Francis Fukuyama and Arthur Kroker, our posthumanB future holds the possibility of a loss

of personal existence through the genetic manipulation of humanB beings. This scenario depicts a

hypo-posthumanB condition.

It represents a decline in humanB existence that could result from

the increase in speed and power associated with various technological

developments, perhaps because of unintended effects of genetic manipulation. We

could designate this sense of a posthumanB condition by the term “postohumanB”

or “pohB.” And since there is a decline in the

possibility of a moral dimension associated with this condition, there is also

a damaging of the humanM condition.

The postohumanB may

thus be correlated with a postohumanM- (pohM-) order. Such a being could be

conceived as postohumanB/postohumanM-

(pohB/M-).

The

technological enhancements that are often associated with transhumanism may

also be conceived as leading to a hyper-posthumanB condition. On this approach, humanB beings might be altered pharmacologically

or through cyber technologies (implants, prostheses) or genetic engineering to

produce a possibly more rational, empathetic, and thus more morally advanced

humanM being. It is also

possible that computers or robots might be produced that are not humanB but morally superior in some ways to

humanB beings (Wallach

2008). This hyper-posthumanB condition

can be designated by the term “postRhumanB” or “pRhB”.

Because such a hyper-posthumanB condition

also results in an improvement in the ability of posthumanB beings to carry out a personal

existence, it would be designated “postRhumanM+ ” or “pRhM+ ”.

While the

complex classification pRhB/M+ applies in this

case, since a morally hyper-posthuman being (pRhM+) can

only be associated with a hyper-posthumanB being (pRhB),

we can refer to a morally hyper-posthuman being (pRhM+)

and it is then implied that it is hyper-posthumanB (pRhB).

The term “posthuman” has such a positive connotation for Rosi Braidotti:

[T]o be posthuman does not mean to be indifferent to the

humans, or to be de-humanized. On the contrary, it rather implies a new way of

combining ethical values with the well-being of an enlarged sense of community,

which includes one’s territorial or environmental inter-connections. (Braidotti

2013, 190)

However, a

hyper-posthumanB condition

might also produce a posthumanB being

that possesses increased intelligence, etc., while lacking a moral sense or

possessing a distorted moral sense (a moral monster like Star Trek’s Khan Noonien Singh). This is the concern that Wendell

Wallach and others, such as Nick Bostrom, have explored with respect to the

possibility of creating moral machines. Superintelligence does not necessarily

correlate with a superior personal existence (Bostrom 2014). Depending on the

circumstances, a hyper-posthumanB condition

might have a positive or negative moral valuation. Accordingly, I propose to

designate a hyper-posthumanB condition that could “lead to a very

rapid extinction of all humans, or something even more hellish” (Roden 2012) as

“postRhumanM- ” or “pRhM- ”. And so, we can see that a postRhumanB condition might be correlated with a

moral advance or decline, whereas a postohumanB condition must necessarily represent a

moral decline.

Thus, any

discussion of a hypo-posthuman moral being (postohumanM-)

must be qualified as to whether it is biologically hypo-posthuman (pohB)

or biologically hyper-posthumanB (postRhB). A

biologically hyper-posthuman moral being may thus be designated pRhB/M+

or pRhB/p0M-. (It is embarrassing

that scientists should employ a complex language to describe the physical world

whereas philosophers are content to speak of “the posthuman.”)

There is,

finally, a posthumanB condition that would represent a state in

which posthumanB persons are equal to humanB persons in

their ability to exercise a personal existence (such a posthumanB

person might, perhaps, be a robot that cannot be distinguished from a humanB

being (posthumanB) or a humanB being who has been altered

pharmacologically to improve mood or memory but remains within the range of

humanB performance (postRhumanB)).10 I designate this possibility by the term

“posthumanB/M=” or “postRhumanM=”. It

would be posthumanM in the sense that it is a post-anthroBpocene

person. A morally posthuman person (posthumanM=/+) is thus a

subclass of moral humanity (humanM), along with humanB

beings. It is not a post-person in the sense of having surpassed personhood. By

way of analogy, if the term “aviation” were taken to include all forms of

flight, we could distinguish between “avian aviation” and “post-avian aviation”

in the case of artificially powered flight. And so, a posthumanB

humanM would be a person that exercises a personal existence in a

way different from the way in which a humanB humanM being

does. The mode of cognition of a computer need not be the same as that of a

humanB being, and nor does an airplane have to flap its wings to

fly. Thus, “The ‘imitation game’ of the Turing Test has misdirected the

ambitions of AI, just as a concern with feathers and flapping misdirected early

efforts at flight” (Ford 2016).

To

illustrate these distinctions further, I would first like to posit a partial

posthuman condition (designated by the term “PPosthumanB) which can

be seen to represent a state between that of the humanB and the

posthumanB. Max More has remarked, in this regard, that we have

taken the first steps in producing posthuman beings:

Clearly we have already taken our first steps along the road

to posthumanity … We have achieved two of the three alchemists’ dreams: We have

transmuted the elements and learned to fly. Immortality is next … Humanity

must not stagnate: to halt our burgeoning move forward, upward, outward, would

be a betrayal of the dynamic inherent in life and consciousness. Let us

progress on into a posthuman stage that we can barely glimpse. (More 1994)

If we

recognize a partial posthumanB condition, as a chain of being

mentality would tend to do, transhumanism may be taken to seek the equivalent of

a partial hyper-posthumanB being (PPostRhumanB)

that corresponds to a partial hyper-posthumanM condition with a

positive moral valence (PPostRhumanM+)

or ppRhB/M+. Such a positive connotation to the term

“PPostRhumanB/M+” (or sometimes “transhuman”) is typical

of transhumanist theorizing. Partial posthumanB possibilities may be

illustrated as:

PPosthumanB = PPosthumanM=

PPostohumanB = PPostohumanM-

PPostRhumanB = PPostRhumanM=

PPostRhumanB = PPostRhumanM- or

PPostRhumanM+

(= Transhuman)

(ppRhB/M+)

We may also posit an end-state model of

the posthumanB that relates transhumanism to the posthumanB

in terms of its goal. Such a target state is what Amitai Etzioni designated, in

The Active Society, as a

“future-system” model. According to Etzioni, “The active society is a

future-system for the analysis of post-modern history” (1968, 572 n). Here the transhuman

(or the state of transition postulated by transhumanists) may be seen as

leading to either a hypo-posthumanB condition, a hyper-posthumanB

condition, or a posthumanB condition. A transhumanism that results

in a hypo-posthumanB condition or a posthumanB one, is a

failed transhumanism since transhumanists seek an improved humanB

condition both physically and morally. The Carnapian approach to concept

construction illustrates the variations that are possible in our conception of

the posthumanB:

HumanB - PPosthumanB /PPostRhumanB = PosthumanM= / PostRhumanM=

HumanB -

PPostohumanB

= PostohumanM-

HumanB - PPostRhumanB = PostRhumanM-

HumanB - PPostRhumanB = PostRhumanM+

Posthuman

prospects

There

are multiple paths to the posthumanB, one of which holds forth the possibility of an

improvement of the humanB species, both biologically and

morally. This is what attracts us to the technologies implicated in the

transhumanist movement. The allure of emerging technologies is the allure of

the possibilities they symbolize. Kierkegaard famously analyzed the role of

possibility in humanB experience and its relation to despair; in

addition to the despair of possibility, he identified a despair of necessity.

Responding to Kierkegaard’s work, Jacques Ellul found both of these forms of

despair to be present in the elaboration of the technological system. As Ellul

remarked, quoting Kierkegaard from Sickness

unto Death,

When technology

makes everything possible, then it becomes itself the absolute necessity.

Necessity which was once the mother of invention, has created an inventive

process which is the mother of a new necessity. “The loss of possibility

signifies: either that everything has become necessary … or that everything has

become trivial.” In fact, with modern technology, both happen at once. (Ellul

1984, 95)

Will our attempt to enhance the cognitive

capacity of humanB

beings lead only to the loss of our ability to make decisions that are ours,

either because the genetic basis of humanM identity has been undermined (as Francis

Fukuyama fears) or because we have given over our decisions to a

superintelligence that is beyond our control (as Nick Bostrom worries)?

Politically, the emerging technologies giving rise to the posthumanB would seem to call for the

kind of democratic planning that Karl Mannheim endorsed, an idea James Hughes

(2004) has updated for the twenty-first century in terms of a democratic

transhumanism. However, if the technologies that can enhance humanB

beings can also be used to mold them so as to manage public opinion, the

approach of democratic planning may be what Ellul called a “political illusion”

(1972). Hans Jonas’ treatment of ethics in a technological age provides what is

perhaps the most honest assessment of our existential condition as we face the

posthumanB age:

[I]t must be

admitted now that this same uncertainty of all long-term projections becomes a

grievous weakness when they have to serve as prognoses by which to mold

behavior – that is in the practical-political application of whatever

principles were apprehended with the help of the heuristic casuistry. … Being

so much in the dark, why not trust our luck including that of posterity? But in

this way, all the gains of our hypothetical heuristics are kept from timely

application by the inconclusiveness of the prognostics, and the finest principles

must lie fallow until it is, perhaps, too late. (Jonas 1985, 30)

Do we even have principles that lie

fallow? Our condition is all the worse if we do not have orienting principles

to guide us in our technological self-alteration from humanB to posthumanB.

And if the movement toward the posthumanB is self-defeating, in that

the attempt to physically improve humanB beings undermines the

possibility of genuine moral improvement, then it seems that our existential

condition (as vulnerable, temporal beings, having imperfect knowledge of the

implications of technological developments) is the only source of orientation

we can rely upon to be able to stand still for a moment, so as to avoid the

whirl of change of emergent technologies. Western philosophy is rooted in an

attempt to find a place to stand so we could move the world. As we set out to

explore the vast ocean of the posthumanB we seem to need what John

P. Doyle called a “philosophical Finisterre.” Doyle explains, “Finisterre is a

cape in northern Spain at the westernmost point of the Spanish mainland. It

marks an end of Europe; beyond Finisterre there is only the ocean” (2012, 215).

Doyle used Finisterre (the end of the

earth) as an image of the farthest point of philosophical speculation he found

the European philosophers of the seventeenth century had reached. For us, a

philosophical Finisterre is a jump off point into the vast ocean of

possibility, a foothold for philosophy at the edge of the human, to use Roden’s

phrase. How might we respond to Jonas’ attitude of resignation regarding

philosophical ethics in a technological age beyond a mere leap of faith?

[H]ere is where

I come to a standstill, where we all come to a standstill. For the very same

movement which put us in possession of the powers that have now to be regulated

by norms – the movement of modern knowledge called science – has by

a necessary complementarity eroded the foundations from which norms could be

derived; it has destroyed the very idea of norm as such. … Now we shiver in the

nakedness of a nihilism in which near-omnipotence is paired with

near-emptiness, greatest capacity with knowing least for what ends to use it.

(Jonas 1985, 22–23)

Notes

1. See Diogenes Laertius 1925, 12. I have

altered Hicks’s English translation, replacing the term “impracticable” with

the term “impassable.” Compare David Roden (2015, 177–78): “The moral of

this tale is that differences in phenomenology can be significant obstructions

to our understanding without being impassable barriers.”

2. I have altered the

translation slightly (see Nietzsche 1917, 221).

3. Compare Pierre Bourdieu 1977, 230–31, n.

110:

The

principle of this antinomy [of otherness and identity] was indicated by Kant in

the Appendix to the Transcendental Dialectic: depending on the interests which

inspire it, “reason” obeys either the “principle of specification” which leads

it to seek and accentuate differences, or the “principle of aggregation” or

“homogeneity,” which leads it to observe similarities, and, through an illusion

which characterizes it, “reason” situates the principle of these judgments not

in itself but in the nature of its object.

(Italics in original)

4.

I have supplied the volume and page numbers for the Royal Prussian Academy of

Sciences edition of Kant’s works.

5.

Compare Plaass 1994, 311: “There [in the Opus

Postumum] it is also frequently said that the MF would have a natural tendency towards ‘transition’ or

‘progression to physics’ (eg., Altpreußische Monatsschrift, XIX, 126; XXI,

143).”

6.

Compare Nason 2014, 6: “The movement of resignation, for de Silentio, is an act

he and every other human agent can do. ‘I can

make the mighty trampoline leap whereby I cross over into infinity; my back is

like a tightrope dancer’s, twisted in my childhood, and therefore it is easy

for me.’”

7.

Compare Roden 2015, 6:

Some philosophers claim that there are

features of human moral life and human subjectivity that are not just local to

certain gregarious primates but are necessary conditions of agency and

subjectivity everywhere. This “transcendental approach” to philosophy does not

imply that posthumans are impossible but that – contrary to expectations

– they might not be all that different from us. Thus a theory of

posthumanity should consider both empirical and transcendental constraints on

posthuman possibility.

8. Again compare Roden:

In

that case, the possibility of posthumans implies that the future of life and

mind might not only be stranger than we imagine, but stranger than we can

currently conceive … Does this mean that talk of “posthumans” is self-vitiating

nonsense? (2015, 6)

9. The following is

developed from Wennemann 2015.

10. I am indebted to

Rebecca Foushée for pointing out this possibility.

References

Appadurai, Arjun. 2013. The future as

cultural fact: Essays on the global condition. London and

Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

Bakker, R. Scott. 2015. Interview with

David Roden. Figure / Ground, June 6.

http://figureground.org/interview-with-david-roden/

(accessed July 5, 2016).

Bostrom, Nick. 2014. Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline

of a theory of practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Braidotti,

Rosi. 2013. The posthuman. Cambridge, UK, and Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Campbell, Jeremy. 1982. Grammatical man: Information,

entropy, language and life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Camus, Albert. 1993. The

Stranger. Trans. Matthew Ward. New York: Knopf.

(Orig. pub. in French 1942.)

Diogenes Laertius. 1925. Lives of eminent

philosophers in ten books. Vol. 2

(bks 6–10). Trans. R.D.

Hicks. Loeb Classical Library ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

(Life of Antisthenes available online at http://www.loebclassics.com/view/diogenes_laertius-lives_eminent_philosophers_book_vi_chapter_1_antisthenes/1925/pb_LCL185.3.xml?rskey=3aQs90&result=79 (accessed July 5,

2016).) (Orig. pub. 3rd century CE.)

Doyle, John P. 2012.

Supertranscendental nothing. In On the borders

of being and knowing: Late Scholastic Theory of Supertranscendental Being,

ed. Victor M. Sala, 215–41. Leuven: Leuven University Press. (Orig. pub.

as: Supertranscendental nothing: A philosophical Finisterre. Medioevo 24 (1998): 1–30.)

Editors of Encyclopĺdia

Britannica. 2015. Great chain of being.

http://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Chain-of-Being (accessed July 5, 2016).

Ellul, Jacques. 1972. The political illusion. New York:

Vintage.

Ellul, Jacques. 1984. The

latest developments in technology and the philosophy of the absurd. In Research in philosophy & technology,

vol. 7, ed. Paul T. Durbin, 77–97. Greenwich, CN: JAI Press.

Etzioni, Amitai. 1968. The active society: A theory of societal and political processes. New York: Free

Press.

Ford, Kenneth. 2016. Cognitive systems

seminar series: On computational wings? Institute for People and Technology

(Georgia Tech).

http://ipat.gatech.edu/hg/item/477961 (accessed July 5, 2016).

Fukuyama, Francis. 2000. Our

posthuman future: Consequences of the biotechnology revolution. New York:

Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Gray,

Chris Hables. 2002. Cyborg citizen:

Politics in the posthuman age. New York: Routledge.

Hughes, James. 2004.

Citizen cyborg: Why democratic societies must respond

to the redesigned human of the future. Cambridge, MA: Basic Books.

Jonas, Hans. 1985. The imperative of responsibility: In search of an ethics for the technological age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kant, Immanuel. 1965. Critique of pure reason. Trans. Norman

Kemp Smith. New York: St. Martin’s Press. (2nd ed. orig. pub. 1781/1787.)

Kant, Immanuel. 1996. Religion within the boundaries of mere

reason, trans. George Di Giovanni. In The

Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant, Religion and Rational Theology, trans. and ed. Allen W. Wood and

George Di Giovanni. New York, Cambridge University Press. (Orig. pub. 1793.)

Kroker, Arthur. 2014. Exits to the posthuman future.

Cambridge, UK, and Malden, MA: Polity Press.

LaGrandeur, Kevin. 2015.

Book review: Robert Ranisch and Stefan Lorenz Sorgner, ed., Post- and Transhumanism: An Introduction.

Journal of Evolution and Technology

25(1) (June 2015): 49–52.

Available online at http://jetpress.org/v25.1/lagrandeur.htm (accessed July 1, 2016).

Liddell, Henry George,

and Robert Scott. 1889. An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon.

Available online at http://perseus.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/philologic/navigate.pl?MiddleLiddell.2 (accessed July 6, 2016).

Locke, John. 1975. An essay concerning human understanding.

Ed. Peter H. Nidditch. New York: Oxford University Press. (Orig. pub. 1689.)

Lovejoy, Arthur O. 1965. The

great chain of being: A study of the

history of an idea. New York: Harper & Row. (Orig. pub. 1936.)

More, Max. 1994. On becoming posthuman.

Available online at http://eserver.org/courses/spring98/76101R/readings/becoming.html (accessed July 6, 2016).

Nason, Shannon M. 2014. Movement/motion.

In Kierkegaard’s concepts Tome IV:

Individual to novel, ed. Steven Emmanuel, William McDonald, and Jon Stewart,

205–212. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

An online version

available at:

http://myweb.lmu.edu/snason/Research_and_Writing_files/Movement%20KRSRR.pdf (accessed July 6, 2016).

Nietzsche, Friedrich, 1917, Thus Spake Zarathustra. Trans. Thomas Common. New York: Modern

Library.

Available online at https://archive.org/details/thusspokezarathu00nietuoft (accessed July 6,

2016).

O’Connor, John K. 2008.

Precedents in Aristotle and Brentano for Husserl’s concern with metabasis. Review of Metaphysics 61 (4) (June): 737–57.

Plaass, Peter. 1994. Kant’s theory of natural science.

Trans., with introd. and commentary, Alfred E. and Maria G. Miller. Dordrecht:

Kluwer.

Pojman, Louis P. 1990. Kierkegaard on faith and freedom. Philosophy of Religion 27: 41–61.

Available online at http://www.sorenkierkegaard.nl/artikelen/Engels/134.%20Kierkegaard%20on%20faith%20and%20freedom.pdf (accessed July 5, 2016).

Richardson, Alan W.

1998. Carnap’s construction of the world:

The Aufbau and the emergence of logical empiricism. Cambridge and New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Roden, David. 2012. Humanism, transhumanism

and posthumanism. Website for enemyindustry: philosophy at the edge of the

human. (Posted June 12.)

http://enemyindustry.net/blog/?p=3348 (accessed July 6, 2016).

Roden, David. 2015. Posthuman Life: Philosophy

at the edge of the human. New York, Routledge.

Sandberg, A., and N. Bostrom, N. 2008. Whole brain emulation: A roadmap. Technical Report #2008‐3, Oxford: Future of

Humanity Institute (Oxford University).

http://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk/brain-emulation-roadmap-report.pdf (accessed July 6,

2016).

Sayers, Dorothy L. 1932. Have

his carcase. New York: Avon Books.

Wennemann, Daryl J. 2013. Posthuman personhood. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Wennemann,

Daryl. 2015. Posthumanisms: A Carnapian experiment. Ethical Technology blog. Institute

for Ethics and Emerging Technologies. (Posted March 19.)

http://ieet.org/index.php/IEET/more/wennemann20150319 (accessed July 5,

2016).