|

A

peer-reviewed electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and ISSN

1541-0099 29(1) – May 2019 |

Can we make wise decisions to modify

ourselves?

Some problems and considerations

Rhonda Martens

University of Manitoba

Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 29 Issue 1 – May 2019 - pgs 1-18

Abstract

Much of the human enhancement literature focuses on the ethical,

social, and political challenges we are likely to face in the future. I will

focus instead on whether we can make decisions to modify ourselves that are

known to be likely to satisfy our preferences. It seems plausible to suppose

that, if a subject is deciding whether to select a reasonably safe and morally

unproblematic enhancement, the decision will be an easy one. The subject will simply

figure out her preferences and decide accordingly. The problem, however, is

that there is substantial evidence that we are not very good at predicting what

will satisfy our preferences. This is a general problem that applies to many

different types of decisions, but I argue that there are additional complications

when it comes to making decisions about enhancing ourselves. These arise not only

for people interested in selecting enhancements but also for people who choose

to abstain.

1. Introduction

Alexis Madrigal, an

American journalist, decided to implant a magnet under the skin of his

fingertip. He came to this decision while interviewing bodyhackers

for an article he was researching. The bodyhackers

spoke with such enthusiasm about how having magnets under their fingertips

opened up new sensory worlds that Madrigal decided to try it for himself. Once the novelty wore off, he discovered that he

did not like having a magnet under his fingertip all that much. He reports that

he sometimes worried about the possibility of infection, and that he would likely

get the magnet removed at some point (Madrigal

2016).

The decision whether

or not to install a magnet under the skin seems a minor one, akin to getting

ears pierced. There are, however, more substantial interventions we can

undertake to change our abilities or our bodies (e.g., Neil Harbisson

implanted a device in the bone of his skull that allows him to hear colors (Jeffries 2014)), and it is likely that more

profound decisions will face us in the future. Many authors discuss the safety

of future possible enhancements (Chatwin et al.

2017; Torres 2016; Douglas 2015; Bostrom and Sandberg 2009), their

influence on our society (Crittenden 2002;

Fukuyama 2003), and their potential influence on our moral selves (Archer 2016; Agar 2014; Persson and Savulescu 2013;

Sandel 2009) and our sense of self (Edelman

2018, Coeckelbergh 2011, Cabrera 2011, Sandel 2009). In what follows, I

will argue that, even if we can successfully address these issues (a tall order

in some cases, but reasonably easily met in the case of Alexis Madrigal’s

choice), we still face the problem that we cannot always know whether our

decision to modify or not modify ourselves will satisfy our preferences.1

Madrigal discovered only after the fact that he preferred the sensation of an

unmodified finger to one with a magnet installed. Furthermore, this problem

faces not only those who are interested in bodyhacking

and enhancement, but everyone, including the abstainers. Once a modification is

contemplated and considered, abstaining is still a choice made without

sufficient information to know that it is the best route to satisfying our preferences.

The decision problem I

am identifying is known in the decision theory literature as making a decision

under uncertainty. After a few preliminaries, I will give a brief,

non-technical description of the problem of deciding under uncertainty. Then I

will present five routes for addressing uncertainty. The bulk of this article

will examine these five routes and the ways in which they can and cannot be

used to make wise decisions about enhancements and body modifications (I use

the term “modification” to signal that in some cases we might want to change

ourselves without making ourselves “better” in some sense). While it is true

that we normally have difficulties figuring out which choices will satisfy our

preferences, I will consider the specific problems that face us when we decide

whether to adopt or reject getting modifications.

Toward the end, I will

consider whether the decision difficulties for modifications are on a par with

other momentous decisions we face. For example, people routinely decide whether

to get married, or to have children, or to pursue a certain career, and we make

all these decisions without sufficient information to know with certainty that

we have made the right choice. I will argue that, for certain types of

enhancement or modification decisions, the lack of information is a more

serious problem than for these other momentous decisions. To clarify, the thesis

is not that we cannot make rational decisions about modifying ourselves. We

can, if we define “rational decisions” as decisions that follow some reasonable

set of decision-theoretic rules. The thesis is also not that we cannot make the

right decision, if this means the one

that leads to the best outcome. It is, after all, possible even for foolhardy

decisions to lead to lucky outcomes. Instead, the thesis is that, when we are

dealing with an information gap, the extent to which rational decisions track

right decisions weakens, and the information gap for certain modification

decisions is larger than for other types of momentous decisions.

My focus here is on

decisions we make on behalf of ourselves, as opposed to decisions we might make

on behalf of others. I will also concentrate on decisions about actions that

are neither morally required nor forbidden. Installing magnets under the skin

seems to fall under this category, and is a relatively minor decision. Note,

however, that non-obligatory, permissible actions can be quite profound in

their consequences or implications. For example, in 2006 the Guardian reported on a case where a

man’s penis was damaged beyond repair in an accident. He opted for a penis

implant, which seems both non-obligatory and permissible. The implant was

medically successful. Nonetheless, surgeons removed the transplanted penis two

weeks later because the recipient and his wife could not psychologically accept

it (Sample 2006). I think it is easy to

imagine why the man consented to the transplant surgery, and easy to imagine

why the results would be sufficiently psychologically disturbing to warrant the

removal of the transplant. It would also be understandable if a year or two

down the road the man regretted his decision to remove the transplanted organ.

This case points to the difficulties in making decisions about how we might

modify our own bodies.

When decisions made on

behalf of oneself are about permissible, non-obligatory actions, many of the

reasons we have for them will be based on whether the decision is likely to

satisfy our personal preferences. These types of reasons are subjective, and they

vary from individual to individual. I will follow L.A. Paul (2014, ch. 2) in calling these types of reasons

first-personal. While it is true that, for some decisions, more objective, or

other-directed, reasons might prevail (for example, we might prefer to remain

unmodified, but might decide to improve our intelligence in order to increase

the odds of discovering a medical treatment that would save the lives of many),

a wide variety of decisions might reasonably involve mostly first-personal

reasons. I will focus on decisions based on

first-personal reasons in this article, although there are further interesting

conversations to be had about decisions involving a mix of first-personal and,

in the relevant sense, objective reasons (Martens 2016 briefly touches on this

subject, although not in the context of decision theory).

Paul argues that, when

the reasons for making a decision are first-personal,

what we need to know is the “what it is like for me,” or the “what it is like

for the agent” (the WIILFA) (Paul 2015b, 808–809).

The WIILFA has two components. The “what it is like” refers to lived

experiences, a kind of “thisness” of the now. The

“what it is like” cannot be fully communicated from one person to another. For

example, there is a difference between being told, “You will hear an extremely

unpleasantly loud noise,” and actually experiencing that noise (Hsee, Hastie, and Chen 2008, 233). The “for me” or “for the

agent” part signals that what matters in making a first-personal decision is

whether the agent will prefer the outcome, rather than whether people in

general, or even people similar to the agent, will prefer the outcome. Some

decisions are going to be more WIILFA-dependent than others. For example, the

WIILFA of “it feels great to be smarter” seems less important than the WIILFA

of “it feels great to be able to hear colors.”

2. Rational decisions

The standard procedure

for making a rational decision involves making a calculation based on the

following pieces of information:

1) The possible ways the world could be (the state) that are relevant

to each choice.

2) The probabilities that the possible states will occur should the

agent make that choice.

3) The outcomes based on the states.

4) The expected values of the outcomes.

The decider will often

lack full information about the above four pieces of information. Furthermore,

lacking information about the first will influence the other three. Before we get

to problems about lacking information, let’s consider a relatively simple

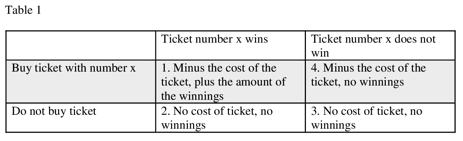

example about buying a lottery ticket (Table 1). The choices are on the

left-hand side of the table. They are: buy ticket with number x; do not buy

ticket. The states are in the top row of the table. They are: Ticket number x

wins; Ticket number x does not win. The outcomes are the results of the choice

and the states, and are numbered in the table from best expected value to worst

expected value.

If we do not consider

the probabilities of each state occurring, then buying the ticket seems the

rational choice because it can give us the highest value outcome. Obviously,

then, we should consider the probabilities. While the expected value of winning

a lottery is high, the probability of winning is low, and so we are more likely

to end up with the worst outcome (outcome 4), rather than the best, if we buy

the ticket. Unless we derive an additional value out of purchasing the lottery

ticket (for example, coworkers might purchase lottery tickets together as a

kind of community-building activity), we should not purchase it. (Outcome 2 can

become the worst outcome if the decider knows she could have bought the winning

ticket. Suppose, for example, she normally selects a specific sequence of

numbers but opts out in the week that those numbers win. Then the decider gets

to add “deep regret” to outcome 2.)

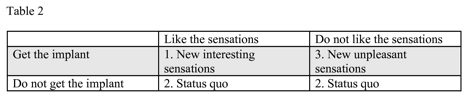

Now let us consider

whether I should get a magnet implanted under my fingertip (see Table 2).

This is a simplified table. For example, I have

excluded the possible state where my finger gets infected. I have also excluded

a category for states that we have not anticipated. I want to note two things.

First, the states in question are experiential and subjective (whether I like

the sensations). Second, since I have never had an implant, the decision is

about whether to have a novel experience. The novelty and subjectiveness

contribute to my not knowing the probability of whether I am the kind of person

who will like the sensations or the kind of person who will not. This implant

decision problem is different from the lottery case. In the lottery case, we do

not know in advance which state will occur (winning or not winning), but we do

know that the probability of winning is very low. We know the probabilities of

the states in the lottery case, but not in the implant case (or, we might

subjectively assign probabilities with a low level of confidence in those

probabilities, but I will not get into such technical issues here). This lack

of knowledge will impair our ability to choose the act most likely to lead to

the best outcome.

This is a simplified table. For example, I have

excluded the possible state where my finger gets infected. I have also excluded

a category for states that we have not anticipated. I want to note two things.

First, the states in question are experiential and subjective (whether I like

the sensations). Second, since I have never had an implant, the decision is

about whether to have a novel experience. The novelty and subjectiveness

contribute to my not knowing the probability of whether I am the kind of person

who will like the sensations or the kind of person who will not. This implant

decision problem is different from the lottery case. In the lottery case, we do

not know in advance which state will occur (winning or not winning), but we do

know that the probability of winning is very low. We know the probabilities of

the states in the lottery case, but not in the implant case (or, we might

subjectively assign probabilities with a low level of confidence in those

probabilities, but I will not get into such technical issues here). This lack

of knowledge will impair our ability to choose the act most likely to lead to

the best outcome.

The problem of making

decisions without knowing with confidence the probabilities of the states is

well known in the decision theory literature, with many approaches offered (for example, Wald 1950, 18; Hurwicz 1951; Savage

1972, ch. 9; Skyrms 1990, 112–14 ; Weirich 2004, ch. 4; Stoye 2011; Buchak

2013, ch. 1). For example, one could follow the rule (the maximin rule) where one makes choices to avoid the worst

outcome, which in this case is outcome 3 (get the implant + do not like the

implant = new unpleasant sensations). Then I should not get the implant. A

different rule would have me considering whether I am risk-averse or

risk-adventurous, and then make my selection accordingly. Since I am

risk-averse, I would make the choice to avoid the worst outcome (outcome 3).

Alexis Madrigal seems more adventurous, at least from his telling of the story,

and he justified his choice because he had an interesting learning experience. According

to this rule, the decision to get the implant is irrational for me, but

rational for Madrigal given our different attitudes toward risk (and given that

the risks associated with implanting magnets are quite low). Notice that these

decision rules are to be applied at the time of making the decision. Below I

will discuss strategies for gathering information prior to the time of making the decision.

If we merely apply

some reasonable decision rule when operating under an extreme lack of

information about the probabilities of the states, then we have reasons for our

decisions. Making a reason-based decision is not the same thing as making the

right decision. The right decision is the one that actually brings about the

best outcome. When operating under an extreme lack of information, a wedge is

driven between reason-based decisions and right decisions. In this context,

reason-based decisions might not perform much better than a guess. Notice that

this problem is symmetrical in the following way. A rule that prioritizes the

status quo is no more likely to track the best outcome than a rule that

prioritizes exploration. When facing modification decisions, we are no more

likely to get it right if we reject the modification than if we adopt it. It is

possible that if we could experience the WIILFA of the modification in advance

of making the decision, we might conclude that the status quo is entirely

unacceptable. The reverse is also possible. Neither transhumanists

nor bioconservatives have an edge here.

Not all is lost.

Sometimes we can take steps to reduce the amount of uncertainty. Here I am

concerned with applied rather than theoretical decision theory, so the goal is

to collect strategies that can be used by real agents rather than ideal agents.

Several authors (Burnett and Evans 2016;

Krishnamurthy 2015; Dougherty, Horowitz, and Sliwa 2015; Pettigrew 2015; Paul

2014, 2015a, 2015b, 2015c; Weirich 2004) focus on realistically usable

strategies. With the exception of the first strategy surveyed below, these

differ from rules like the maximin rule in that they concern

how we should gather information or frame the decision. These are strategies

for preparing for a decision prior to applying a decision rule. I will survey these

five strategies before applying them to decisions about body modification. Not

all of these strategies will turn out to be good strategies for making

decisions about body modification, and all of them will have limited applications.

3. Five strategies for dealing with uncertainty

3.1 – High need or low cost

The idea here is that,

while we face a lack of information about the WIILFA of the novel experience,

we may still have enough information to make a choice. In the high need case,

the costs of not changing are high enough to motivate trying a novel

experience. For example, having a currently untreatable fatal disease could

make it rational to try an experimental treatment despite a lack of information

about effectiveness or safety (for an

introduction to dominance, see Whitmore and Findlay 1978, 24–27). In the

low-cost case, while we might not know whether we will prefer the WIILFA of the

novel experience, the costs of trying are low enough to be worth finding out.

The low-cost case can be buttressed by a decision rule focused on avoiding

regret. The strategy of appealing to high needs or low costs clearly has

limited applications, as will be discussed in section 4.

3.2 – Curiosity

We could justify

trying the novel experience on the grounds that we value discovering what it

will be like. This way, at least one of our preferences – the preference to

discover what it will be like – will be satisfied regardless of what the other

aspects of the experience will be like. This is a reframing strategy proposed

by Paul in response to the failures associated with the next option (Paul 2014, ch. 4). As we shall see in section

4, the curiosity option has extremely limited applications. Furthermore, the

adventurous might find themselves regretting their adventures if the outcomes

are bad enough.2

3.3 – Imagination

We could use our

imaginations to try to determine what the novel experience will be like for us.

Paul refers to this as a natural approach, which we use for many types of

decisions (Paul 2015c). For example, when

deciding on purchasing a new home, one might begin the decision process by imagining

living in the home.

Paul also insists that

using our imagination is a necessary approach when decisions depend on the

value of the WIILFA for our future selves undergoing the experience.

Imagination, Paul argues, is the only way to grasp what our unique future

selves will be like because empirical studies can only be about other people

who may or may not resemble our future selves (2015b, 448–87). The problem, which Paul acknowledges and

will be elaborated on in section 4, is that our imagined future self is not

likely to resemble our actual future self in the way that we need.

3.4 – Prototyping

Weirich (2004, 27) points out that rational agents will not

simply rest content with applying decision rules to the information they have,

but will collect new information whenever possible (a sequential versus a

static approach to decision theory). He highlights the strategic value of

making a series of decisions, each of which leads to acquiring new information

that influences the next decision. In their self-help book on making decisions,

Burnett and Evans offer similar advice from a less academic perspective (2016, ch. 6). They recommend prototyping, which involves seeking

out lower risk experiences that are similar to the novel experience we are

considering trying. For example, if we want an RFID chip implant in our hands that

will allow us keyless entry into our homes, we could try the chip on a wearable

device first. Krishnamurthy (2015) offers a similar suggestion when she argues

that we can obtain information about what it will be like to be a parent by

spending lots of time caring for children. This involves an argument by analogy, that the prototyped experiences we have had in the

past are sufficiently similar to the experiences we will have in the future if

we make the higher risk decision. This strategy and the next are the most

promising routes, although their limitations will be discussed in the next

section.

3.5 – Collecting empirical data

The most common advice

in the literature is to collect more information about the probability of the desired

states by consulting empirical studies (quantitative or qualitative) of others

who have already made the same decision (Krishnamurthy

2015; Dougherty, Horowitz, and Sliwa 2015; Pettigrew 2015). If we are

considering a body modification, we should find out if others who have already

tried the modification found it to be a valuable experience. This also involves

an argument by analogy, to the extent that we are relying on those people being

similar to us in relevant ways. This is not a watertight argument, however. After

all, they might prefer the experience while we do not.

Note that strategies

3, 4, and 5 (imagination, prototyping, and collecting empirical data) involve

trying to gather information on the probabilities of whether the subjective

experiences will be valuable to us. In other words, the problem of uncertainty

is addressed by reducing the level of uncertainty. Strategy 2 (curiosity) does

as well, but in a different way. It involves shifting focus from future states including

or not including the WIILFA to states about discovering or not

discovering the WIILFA. The agent might not know whether she will like the

WIILFA, but she will have information about whether she values discovery or is

risk-averse.

Strategy 1 (high need

or low cost) does not involve basing justification on an approximation of the

expected value of the WIILFA of the novel experience at all, but on either the

known bad expected value of the WIILFA of the known outcome or the known low

risks of the novel option. Whatever might be the expected value of the novel

WIILFA, it stands a good chance of being better than the WIILFA of the known

outcome, or in any event it is unlikely to be bad enough to avoid.

4. The main argument

It is now possible to

state an outline of the argument of this article:

1) In order to be reasonably confident that our decisions will satisfy

our first-personal preferences about the WIILFA, we need to reduce sufficiently

the amount of uncertainty associated with a decision. This applies equally to

the decision to stay the same as it does to the decision to change or enhance

oneself.

2) For many people, and for certain types of modifications, the above

five strategies are either inadequate or unavailable for reducing sufficiently

the amount of uncertainty associated with a decision. (This is especially likely

in the early stages of modification research. If modifications come into

widespread use, we will be presented with different problems, discussed below.)

3. Therefore, if the above

five strategies are the only routes for sufficiently reducing uncertainty, then

for many people, and for certain types of modifications, a reasonable amount of

confidence that decisions will satisfy first-personal preferences cannot be

obtained.

It is worth noting

that we are currently facing this problem. I have already not installed

magnets under my fingertips many times. If you are like me, then you will also

have made many such decisions without a great deal of thought.

One

obvious vulnerability of the

argument, implicit in the wording of its conclusion, is the possibility of some

strategy not in the list of five mentioned above. Any further justification

strategies will make for interesting discussion at another time. I cannot deal exhaustively

with the issue on this occasion, although at the end of the article I will

speculate briefly on routes we might take. Meanwhile, the bulk of what follows

will focus on justifying premise 2. I will examine each of the suggested

strategies, in order to show why they do not always apply.

4.1 – High need

or low cost

It is possible to make

rational decisions when the outcomes of a novel course of action are unknown if

the outcomes of the other course of action are known to be sufficiently worse.

For example, in the 1980s, many people infected with the human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) were willing to try experimental drugs because the known outcomes

of not trying the drugs were severe.

It would be far too

quick to rule out this justificatory strategy for enhancements on the grounds

that enhancements are not treatments. Aside from the

oft-noted blurry boundary between enhancements and treatments (see, for

example, Agar 2014; Lara 2017), sometimes enhancements are still solutions to

problems. This justificatory strategy is not limited to life and death

situations. All that is needed is enough information to be able to conclude

reasonably that, whatever the outcomes might be from the novel course of

action, they are very likely to be better than those of the non-novel course.

I have grouped the

high-need reason together with the low-cost reason because they both depend on

a proportional bar of risk. If the possible risks of the novel action are

reasonably low, then the problem it is intended to solve does not need to be

severe. Consider the magnet case. While it is novel, and we might be in the

dark about whether we will like the insertion of a subcutaneous magnet, we

still have a pretty good idea of some of the risks. They are fairly low. We

know, to use an absurd example, that installing magnets under our skins will

not turn us into frogs. Since the range of possible outcomes of installing a

magnet are not extremely bad, the problems that magnets could solve also do not

need to be extreme. They only need to outweigh the range of possible negative

outcomes. Let us consider a few examples of enhancements that are solutions to

problems.

Amal Graafstra had the problem

of leaving his keys in his office and locking himself out. He solved his

problem by installing an RFID chip implant under the skin of his hand that

unlocks his door. Now he does not lose his keys anymore (Graafstra 2013).

Neil Harbisson is a visual artist who was born completely color

blind. Nonetheless, he wanted to work artistically with colors, so he installed

a device that is fused to his skull and allows him to hear colors (Jeffries 2014).

In an article on bodyhacking published in the New York Times, Hylyx Hyx

is quoted as saying, “I’m used to having weird feelings about my body . . . I

use ‘they’ pronouns. I don’t care about most of my meat, so this is a way to

have control over a part that I chose” (Hines

2018). One way to interpret Hyx is as

expressing a lack of connection with their body, and a desire to control it.

Through body modification, Hyx can now control and

connect to their body.

Hylyx Hyx also stated that they

are a “submissive for science” (Hines 2018). One interpretation of this claim

is that Hyx is willing to be an experimental subject.

It is possible that such experiments could lead to treatments that address not

the high needs that Hyx has, but needs that others

have. This, however, is not a common motivation.

Liao, Sandberg, and Roache (2012) argue that if we enhance ourselves

and our offspring so that we consume fewer resources and are more

intelligent and ethical, we might be able to find a solution to the pressing

problem of climate change.

Back

to the HIV case. It would not

normally be rational to try an untested drug if another known effective drug

were available. In the above four examples, there are alternative solutions to

the problems. Graafstra and Harbisson

could use wearables. Hyx could

stick to piercings, tattoos, or diet plus the gym to control their body. For

the problem that Liao, Sandberg, and Roache raise, our

respective governments could better incentivize good environmental behaviors on

our part (which seems a more likely successful route than incentivizing that we

modify ourselves and our offspring).

It is possible that Graafstra, Harbisson, and Hyx would find my alternative proposals unacceptable. They

could, for example, have deep identity-based reasons for why implants, even

implants with potentially negative consequences, are a more palatable way to go

than the alternatives. I do not know them personally, so I cannot say what

their reasons are, but it is certainly conceivable, and even likely, that some

people might have deep identity-based reasons for wanting to modify their

bodies in certain sorts of ways, even if Graastra, Harbisson, and Hyx themselves do

not. For an identity-based reason to count as a high enough need to swamp other

considerations, it would need to be similar to what many trans*3

people experience when deciding whether or not to transition. Rachel McKinnon offers

a version of this decision-making strategy when she points out that, while

trans* people might not know what it will be like to transition, they are often

faced with dire situations if they do not. To support this, she cites studies of

high suicide rates of trans* people (McKinnon 2015, 423–24). Similarly, White

cites studies of the suffering of people with Body Integrity Identity Disorder

who are prevented from obtaining elective amputation for the purposes of

aligning their bodies with their identities (White 2014, 226).

Even if, however, we

can successfully argue that identity expression through body modification is

important enough to swamp the possible negative outcomes, it also seems likely

that this method of justification will be available only to some people. Many others

will not feel driven by identity reasons to expand their abilities or modify

their bodies. Thus, to the extent that the identity threat argument works, it

will work only for some. Furthermore, many of the enhancements and

modifications that we might consider are not solutions to any problem at all. Therefore,

the high need/low cost approach is a justificatory strategy with limited

application.

4.2 – Curiosity

The adage, “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread” is one description

of what happens when people base a decision to try the novel on curiosity. Here

is another description. Paul proposes that we can reframe the decision problem

in a way that permits a rational decision to be made. The idea is this. Instead of trying to ascertain which option will

increase first-personal value based on an unknowable WIILFA, we might base the

decision on whether we value finding out the WIILFA. For example, if we value

knowing the WIILFA of having magnets under the skin of our fingertips, we will

satisfy that value regardless of what the WIILFA turns out to be (Paul 2014, ch. 4). In Alexis Madrigal’s case,

given the tone of his report, it seems that he valued having the implant

experience for the purpose of finding out what it would be like, even though,

in the event, he did not particularly care for the what-it-was-like. (We can

use this reframing strategy not just for values such as a discovery preference,

but also for values such as controlling one’s body.)

We can also use this

reframing strategy for rejecting the

novel experience. For example, it is quite reasonable to value not finding out the WIILFA of

age-related cognitive decline, so taking a preventative drug to avoid having

that discovery is rational.

There are at least two

ways in which the valuing discovery option is limited. First, for certain types

of decisions, it counts as a terrible reason. Consider Paul’s stock example of

choosing to have a child for the first time. Having a child for the sake of wanting

to find out the WIILFA seems incredibly flippant. This level of flippancy might

be reasonable when it comes to more trivial decisions like installing magnets

or RFID chips under the skin, but not for deciding to have a child or deciding

to take on a more profound enhancement. The level of risk matters here. Also,

in the case of deciding to have a child, other parties are deeply affected by

our decision. (Interestingly, the flippancy seems to disappear when we consider

the decision to not enhance or to not have a child. Wanting to not find out the

WIILFA seems acceptable here.)

Second, only a

relatively small number of people will be able to make use of the curiosity-justification

strategy. Basing a decision on valuing discovery is available to those for whom

wanting to find out the WIILFA is a sufficient reason to adopt an enhancement.

It is also available to those for whom wanting to not find out the WIILFA is a sufficient reason to avoid an

enhancement. Basing a decision on valuing discovery is not available for the

following two groups: those for whom these wants are not sufficient (e.g., I am

kind of curious about having an RFID chip implant, but not enough to override

my concern about uncertainties about the WIILFA); and those who do not have

wants either way about discovering the WIILFA. Let us explore the latter point.

There is a distinction

between wanting to not find out the

WIILFA, and not wanting to find out the WIILFA. The first involves an active

desire to avoid learning about the experience. For example, I have an active

desire to avoid finding out what it feels like to jam a pencil into my hand.

The second involves the absence of an active desire. For example, I do not have

any desires one way or the other to find out the WIILFA of having arms that are

1 centimeter longer than they currently are.

While it seems pretty

clear that the bodyhacking movement is driven forward

in part by curiosity (along with other desires, such as controlling one’s body)

– and so, many bodyhackers can avail themselves of

this justificatory strategy – the bodyhacking

community is relatively small. It seems very likely that many people will fall

into the categories of either not having a sufficient desire to discover/avoid

finding out the WIILFA or not having a desire at all about the discovery aspect

of enhancement. These people, then, are still faced with the problem of

justifying their decision either to try or to avoid the novel enhancement.

4.3 –

Imagination

A large body of

literature in psychology shows that we are terrible at predicting whether, or

how much, we will prefer an experience (Wilson and Gilbert 2005; Gilbert et al.

2009; Walsh and Ayton 2009). We are terrible at this even when the predictions

in question involve events we have experienced many times in the past. For

example, if we are still full from the last delicious meal, we tend to

underestimate how much we will enjoy the next delicious meal. Yet we have gone

through the process of moving from satiety to hunger many times in our life.

Given this, we can expect to be terrible at predictions about the

first-personal values of novel experiences. As some authors have previously pointed

out, future research on human enhancements might take us in directions that

boggle our imagination (Mihailov and Dragomir

2018).

It is worth taking a

few moments to review one of the identified errors we tend to make when trying

to ascertain whether we will prefer a new experience, and whether the price we

pay for that new experience is suitable. Forewarned is forearmed. We tend to

overestimate how much we will react to a future event (Wilson and Gilbert 2005). To use Hsee,

Hastie, and Chen’s (2008) example, when we first move into a larger home, our

initial feelings of pleasure will be stronger at the start. Later, however, we

will adjust to this larger home, and the intensity of the pleasure will

decrease. Hsee, Hastie, and Chen refer to this as the

distinction between acquisition and consumption. When deciding whether or not

the larger home is worth the greater expense, we often make the mistake of basing

our decision on the prediction of the acquisition experience rather than the

consumption experience.

Similarly, when

considering modifying the body, we might make the mistake of basing our

assessment on a prediction of the acquisition experience rather than the

consumption experience.

4.4 – Prototyping

If the problem of

uncertainty arises because we do not have past experiences that are

sufficiently similar to the future experiences we are considering, we may make

lower risk decisions that give us information about those future experiences.

Earlier, I gave examples such as wearing an RFID chip on a ring before

implanting it in the hand. For another example, Neil Harbisson,

prior to fusing a device to his skull that allows him to hear colors, wore a prototype

that strapped onto his head. This allowed him to gather significant information

on whether or not the device worked, and whether or not he could learn the

color-to-sound language (Stix 2016).

Prototyping has its

limits. One feature Harbisson could not prototype was

the WIILFA of having the device fused to his skull. Another feature that cannot

be prototyped is the long-term WIILFA. As previously mentioned, there is a

difference between the acquisition experience and the consumption experience,

and this difference matters.

Other enhancement

choices might not be suitable for prototyping at all. For example, it is

difficult to imagine how one would prototype being substantially smarter (a

little bit smarter, yes, but substantially smarter is more difficult).

4.5 – Collecting

empirical data

When making decisions, it can be useful to find out how other people

value the outcomes of their choices. We could talk directly to people about

their experiences, or read the narratives contained in qualitative studies, or

look at the results of quantitative studies. For this approach to provide us

with information about the probabilities of outcomes that satisfy our

preferences, two conditions must be met. First, there must be people who have

already made the decision in the past. Second, those people must be

sufficiently similar to us in relevant respects for the information about their

experiences to be predictive of ours. Relevant dissimilarities will weaken the

argument by analogy.

Let us consider three stages. Stage 1 is where nobody has yet tried the

modification. Stage 2 is where only early adopters have tried it. Stage 3 is

where the modification is widely used. Obviously, the stages will not, in

practice, be sharply delineated. Nonetheless, the question remains. How do we

get from Stage 1 to Stage 2, and from Stage 2 to Stage 3?

When moving from Stage 1 to Stage 2, the first condition cannot be met.

We cannot find out how others have valued the experience because nobody, to

date, has had the experience. Early adopters will need to make use of some

other method of justification. To quickly review, the high risk or low cost

strategy requires either that the status quo be high risk or the modification

be low cost. There will be some modification decisions that do not fall into

either of these categories. Valuing discovery for its own sake might be

appealing to early adopters, but again, the strength of the desire for

discovery needs to increase proportionately with the risk of the modification. Imagination is very inaccurate, and pretty much a

non-starter. Prototyping is useful, but only certain aspects of the novel

experience can be prototyped.

What are we left with? Here are three ways to move from Stage 1 to Stage

2:

1) Some people might adopt early because

their modifications are also treatments.

2) Those with a high desire for discovery might

move us from Stage 1 to Stage 2.

3) Those who make decisions without giving

them much thought might also show up in the early adoption crowd.

It is interesting to think that, in moving toward a posthuman

future, we might be relying on thoughtless behavior. As a quick aside, however,

thoughtless decision-making can sometimes be beneficial. I imagine that many

can identify with the claim that, had we given enough thought to certain

decisions (e.g., having a child or training to become a professor), we might

not have made those decisions, but we are nonetheless glad that we did.

When we move from

Stage 2 (early adopters only) to Stage 3 (widespread use), we now have people

who can report on their experiences. The question is whether early adopters are

sufficiently similar to late adopters to support an argument by analogy. Since

we are focusing on decisions that are based on satisfying preferences about the

WIILFA, what matters is whether early adopters are sufficiently psychologically similar to late adopters.

Physiological similarity between the two groups is important for establishing

medical safety and effectiveness, but psychological similarity is needed to

support the claim that, because the modification satisfied the preferences of

the early adopters, it is likely to satisfy the preferences of the late

adopters. I will argue that there are roadblocks to establishing similarity in

preference sets between the two groups. These are not insurmountable, but they

are cause for concern. We will begin with general problems on reports of the

WIILFA, and then move to problems more specific to modifications.

The first general

problem has to do with interpreting other people’s reports of their WIILFA. Hsee, Hastie, and Chen observe that, while we can use other

people’s reports to provide information, information is “cold” while

experiences are “hot.” There is an important experiential element that does not

get communicated (Hsee, Hastie, and Chen 2008, 233).

The second general

problem is with how people report on their decisions. People tend to

rationalize decisions after the fact for a variety of complicated psychological

reasons (Mather and Johnson 2000; Mather, Knight

and McCaffrey 2005; Stoll Benney and Henkel 2006). This reduces the

reliability of testimonials. On the plus side, the tendency to rationalize

makes it likely that, whatever future decisions we make, we are likely to rate

them more positively than, perhaps, we should.

For problems more

specific to modification decisions, the reasons early adopters have for their

decision might be different from those of late adopters, and these differing reasons

might reflect different preference sets. Consider the early adopter who selects

the modification as a treatment. One significant preference is to be relieved

of the condition being treated. For the early adopter who selects the

modification out of a sense of adventure, preferences for discovery, and even

risk, will be salient. The thoughtless early adopter might have a positive

attitude toward risk, at least with respect to the selected modification

(although there can be many reasons for thoughtlessness). In sum, the early

adopters might include some people who are merely thoughtless, but others are

likely to have relevantly different preferences from the late adopters. One question

that remains is whether these different preferences influence earlier and later

groups’ perceptions of the WIILFA.

There is data to

suggest that the context in which a decision is made influences the decider’s

perception of the experience and the extent to which it satisfies preferences.

For example, if a Positive Experience 2 follows another Positive Experience 1,

we are inclined to rate Positive Experience 2 less highly than we would if it

had followed Negative Experience 1 (Kahneman 1992).

For someone selecting a modification as a treatment, and assuming the treatment

is successful, we have a positive experience following a negative one. For

another example, if a decision leads to the satisfaction of a goal, we tend to

rank the experience more highly than if the decision leads to failing a goal,

even if the actions and outcomes are the same (Heath, Larrick,

and Wu 1999). For those motivated to modify out of a sense of adventure, this

type of framing could influence reports of preference satisfaction.

It is striking that,

given the identifiable differences in preferences between late adopters and those

early adopters who are motivated either by needing a treatment or by a desire

for discovery, the most suitable group for building an analogy between early

and late adopters is the sub-set of early adopters who acted thoughtlessly. The

thoughtless group is more likely to be diverse, since there can be many reasons

for acting without thought. One issue that will matter is whether the

thoughtlessness is global or local. If it is global, then it is hard to see how

late adopters can trust the reports given by the thoughtless.

To be sure, the

decider and the reporter (i.e. the early adopter) can keep these factors in

mind. The reporter can be careful in how she articulates the nature of her

experiences. The decider can sift through this information with awareness of the

roles that psychological biases might play. The late adopter does not have

perfect information, but the early adopter’s report gives him more information

than he had in Stage 1. In assessing this, the late adopter needs to be aware

that the differences between early adopters and late adopters weaken the

analogy between their respective experiences. How much this matters depends on

the magnitude of the risk if one makes the wrong decision. It also depends on

just how different the late adopter is from the early adopter. Realistically,

attitudes to early and late adoption will come in degrees. We might have

early-early adopters who provide reasonable information for early adopters, and

then the early adopters can provide reasonable information to early-late

adopters. And so on. This would be a gradual rolling out of inferences. That

said, in the early stages of Stage 2, the late-late adopters will

still have a significant information gap. I emphasize again that this is a

problem not just for those considering adopting a novel modification, but also

for those who are not. Failing to make a decision and deciding to avoid an

experience are still choices.

We also need to

consider the problem in moving from Stage 2 to Stage 3 in the context of

certain transhumanist philosophies. Neil Harbisson and Moon Ribas,

co-founders of the Cyborg Foundation, articulate a vision of a world in which

people design their own modifications in keeping with their specific desires

about how they want to interact with the world (Harbisson

and Ribas 2018). Clearly, on this vision, if we design a unique

modification, we will not have access to information about how others have

experienced it. I should note that Harbisson and Ribas recommend prototyping on their website.

5. Concluding remarks

In an article about

the ethics of human enhancement, Norman Daniels recalls an old joke about a

traveler asking for directions of a farmer. The farmer, after considering a

variety of routes, says, “You can’t get there from here.” Daniels’ point is that

we cannot ethically and safely get from our current world to one where

modifications are profound and widely used (Daniels

2009, 38–41). My point is less emphatic. If we want to get from here to

there while making informed decisions about whether the modifications will

provide us with WIILFAs that satisfy our preferences, we will encounter

significant roadblocks.

It might seem from the

foregoing that I am recommending a bioconservative position.

I am not, and these are some reasons why I am not. As already mentioned,

neither the bioconservative nor the transhumanist has the edge on increasing the odds of making

the right decision (the one that will yield the best WIILFA). Furthermore, if

we think that we can avoid this decision problem by simply avoiding research

into enhancement and modification techniques, then we

are mistaken. Avoiding research is itself a potentially mistaken choice.

Finally, and this is more of a confessional comment than anything else, I am

personally enthusiastic about the possibility of a posthuman

future such as envisaged by transhumanists. The

problem is that the future I enthusiastically imagine is one with all the bugs

and decisions already worked out, and I do not know how we can get from here to

there. I applaud Hylyx Hyx

for their willingness to be a “submissive for science” (Hines 2018), but I personally am not willing to go down that road.

I think that Ronald Dworkin put his finger on why the prospect of new human

enhancement techniques is so troubling. Dworkin, in

trying to sort out what the reasons might be for the “playing God” objection to

human enhancement, observes that when scientific developments present us with

choices we did not previously have, our views on ethics and justice get changed

in a way that he calls “seriously dislocating” and requires a significant

readjustment period (Dworkin 2002, 444). Dworkin argues that the reason our views on ethics and

justice get changed is because our ideas about responsibility depend on the

border between chance and choice. New scientific developments can change this

border. Similarly, the prospects of novel enhancements and modifications present

us with a “seriously dislocating” set of new decisions.

As Bostrom

and Ord point out, modification decisions are not the

only ones we have to make without sufficient information. Decisions about

careers, becoming parents, and getting married are all high stakes decisions

that we make without knowing whether they will turn out for the best (Bostrom and Ord 2006, 657). There is, however,

one key difference between, for example, the decision to become a parent and

the decision to adopt a radically new way of sensing the world. Many people

like us have become parents before. We do not have a guarantee that our choice

to become a parent will, on balance, be a good choice, but we do have access to

a reasonable amount of information about this choice. Until we get to Stage 3

with modifications, decisions about modifying ourselves in novel ways will not

be on a par with decisions about becoming parents or getting married or

selecting a career.

Where do we go from

here? Novel decisions are coming whether we like it or not. Marcus Arvan has an interesting answer, which he raises in the

context of discussing transformative choices such as whether to become a

parent. He proposes that instead of trying to fix the decision problem, we

should work on becoming more resilient people so that we can adapt fruitfully

to whatever outcomes arise (Arvan 2015).

While this sounds like sage advice, I am troubled by the thought that, should I

wind up making a modification that provides me with a negative WIILFA, I should

rest content with the knowledge that I am the kind of person who will make the

best of it. The bioconservative faces a similar

problem in resting content with the idea that, even if he avoided selecting a

beneficial modification, he should make the best of it. More disquieting is the

tacit admission that, because of our psychology and our lack of access to

information, we simply do not have a good decision toolkit available to

navigate the types of decisions we will soon be facing about how we want to

change our bodies and ourselves.

More promising are the

suggestions that we attend to prototyping and empirical evidence. Here are just

a few brief considerations. As already mentioned, not all aspects of a novel

experience can be prototyped. One point of concern is that it will be

particularly difficult to prototype duration (if the decider is considering a

permanent change, then this permanence cannot be prototyped in advance).

Another concern is that the prototype, by definition, will not be at the same level

of risk because prototyping involves making lower risk decisions in advance of

the higher risk decision. Finally, since some modifications can be more easily

prototyped than others, this might influence the direction of research on

modifications in much the same way that activity trackers that only measure

steps might encourage a focus on step-based exercise over other forms of

exercise.

When it comes to

relying on empirical evidence, one way to strengthen the analogy between the

early and late adopters (Stage 2 to Stage 3) is to introduce modifications

incrementally. The differences between early and late adopters need not be so

strong when the modification in question is a modest change. The worry, though,

is that, if we pursue this route, we are deciding not to pursue more dramatic

modifications at the moment, and this decision might be the wrong one. We might

be able to satisfy preferences about the WIILFA by rolling out modifications

quickly.

In this article, in

addition to focusing on decisions made about satisfying preferences about the

WIILFA, I have been focusing on individual decisions made in isolation. The

decisions others make will influence the calculation in a way that complicates

things tremendously. For example, those who get value from the novelty factor

will find out that the value of their modification decreases as others start to

adopt it. For another example, refusing a modification might initially be the

right move, but as others adopt it, a variety of pressures might be brought to

bear on the refuser that will change the values of

the outcomes. Consider the fact that it is increasingly difficult to navigate

our modern world without a cell phone, which puts pressure on people to

purchase one. Similar types of market and social forces could put pressure on

people to modify themselves, which could increase the costs of not modifying.

Ultimately, after considering ways to improve on the information we have to inform

our own individual decisions, we will need to turn to the herculean task of

sorting out rational decisions in a context where the decisions that others

make will influence which decisions are rational for us.

Notes

1. I am not staking a

claim on the nature of well-being by focusing on

preference satisfaction, because I am not claiming that satisfying preferences

is the key to well-being. Instead, I am simply focusing on the types of

decisions that appropriately depend on preference satisfaction. There are many

other types of decisions we might make, and some of those other types might be

instrumental in improving well-being.

2. Thanks to an

anonymous reviewer for this and many other insightful observations.

3. Rachel McKinnon

uses the convention “trans*” as an inclusive term referring to a variety of

transgender identities.

References

Agar, Nicholas. 2014. A question about defining moral

bioenhancement. Journal of Medical Ethics

40: 369–70.

Archer,

Alfred. 2016. Moral enhancement and those left behind. Bioethics 30: 500–510.

Arvan, Marcus. 2015. How to rationally approach life’s

transformative experiences. Philosophical

Psychology 28: 1199–1218.

Binmore, Ken. 2009. Rational

decisions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bostrom, Nick, and Toby Ord. 2006. The reversal test: Eliminating

status quo bias in applied ethics. Ethics

116: 656–79 .

Bostrom, Nick, and Anders Sandberg. 2009. The wisdom

of nature: An evolutionary heuristic for human enhancement. In Human enhancement, ed. Julian Savulescu

and Nick Bostrom, 375–416. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Buchak,

Lara. 2013. Risk and rationality:

Oxford University Press.

Burnett, Bill, and David John Evans. 2016. Designing your life: How to build a

well-lived, joyful life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Cabrera, Laura Y. 2011. Memory enhancement: The issues

we should not forget about. Journal of

Evolution and Technology 22(1): 97–109 .

Chatwin, Caroline, Fiona Measham, Kate O’Brien, and

Harry Sumnall. 2017. New drugs, new directions? Research priorities for new

psychoactive substances and human enhancement drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy 40: 1–5.

Coeckelbergh, Mark. 2011. Vulnerable cyborgs: Learning

to live with our dragons. Journal of

Evolution and Technology 22(1): 1–9.

Crittenden, Chris. 2002. Self-deselection:

Technopsychotic annihilation via cyborg. Ethics

and the Environment 7(2): 127–52.

Daniels, Norman. 2009. Can anyone really be talking

about ethically modifying human nature? In Human

enhancement, ed. Julian Savulescu and Nick Bostrom, 25–42 . Oxford and

NewYork: Oxford University Press.

Dougherty, Tom, Sophie Horowitz, and Paulina Sliwa.

2015. Expecting the unexpected. Res

Philosophica 92: 301–21.

Douglas, Thomas. 2015. The harms of enhancement and

the conclusive reasons view. Cambridge

Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 24: 23–36.

Dworkin, Ronald. 2002. Sovereign virtue: The theory and practice of equality. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Edelman, Shimon. 2018. Identity, immortality,

happiness: Pick two. Journal of Evolution

and Technology 28(1): 1–17 .

Fukuyama, Francis. 2003. Our posthuman future: Consequences of the biotechnology revolution.

New York: Picador.

Gilbert, Daniel T., Matthew A. Killingsworth,

Rebecca N. Eyre, and Timothy D. Wilson. 2009. The surprising power of

neighborly advice. Science 323:1617– 619.

Graafstra, A.

2013.

Biohacking – the forefront of a new kind of human

evolution: Amal Graafstra

at TEDx SFU. YouTube video file, posted October 17,

2013. Duration 16:38. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=88&v=7DxVWhFLI6E (accessed May 7, 2019).

Harbisson, Neil, and Moon Ribas. 2018. Cyborg

Foundation, history.

https://www.cyborgfoundation.com/ (accessed June 6,

2018).

Hines, Alice. 2018. Magnet implants? Welcome to the

world of medical punk. New York Times.

May 12.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/12/us/grindfest-magnet-implants-biohacking.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=second-column-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news

(accessed May 21, 2018).

Hsee, Christopher K., Reid Hastie, and Jingqiu Chen.

2008. Hedonomics: Bridging decision research with happiness research. Perspectives on Psychological Science 3:

224–43.

Hurwicz, Leonid. 1951. Optimality criteria for

decision making under ignorance. Cowles Commission Discussion Paper, Statistics

no. 370.

Jeffries, Stuart. 2014. Neil Harbisson: The world’s

first cyborg artist. The Guardian.

May 6.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/may/06/neil-harbisson-worlds-first-cyborg-artist

(accessed May 21, 2018).

Kahneman, Daniel. 1992. Reference points, anchors,

norms, and mixed feelings. Organizational

Behavior and Human Decision Processes 51: 296–312.

Krishnamurthy, Meena. 2015. We can make rational

decisions to have a child: On the grounds for rejecting L.A. Paul’s arguments. In

Permissible progeny?: The morality of procreation

and parenting, ed. Sarah Hannan, Samantha Brennan, and Richard Vernon, 170–83.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Lara, Francisco. 2017. Oxytocin, empathy and human

enhancement. Theoria: An International

Journal for Theory, History and Foundations of Science 32: 367–84.

Heath, Chip, Richard Larrick, and George Wu. 1999.

Goals as reference points. Cognitive

Psychology 38: 79–109.

Liao, S. Matthew, Anders Sandberg, and Rebecca Roache.

2012. Human engineering and climate change. Ethics,

Policy & Environment 15: 206–21.

Madrigal, Alexis. 2016. I got a magnet implanted into

my finger for science, and it was amazingly weird. Splinter. April 6.

https://splinternews.com/i-got-a-magnet-implanted-into-my-finger-for-science-an-1793856036

(accessed May 18, 2018).

Martens, Rhonda. 2016. Resource egalitarianism,

prosthetics, and enhancements. Journal of

Cognition and Neuroethics 3(4): 77–96.

Mather, Mara, and Marcia K Johnson. 2000.

Choice-supportive source monitoring: Do our decisions seem better to us as we

age? Psychology and Aging 15: 596–606.

Mather, Mara, Marisa Knight, and Michael McCaffrey.

2005. The allure of the alignable: Younger and older adults’ false memories of

choice features. Journal of Experimental

Psychology: General 134: 38–51.

McKinnon,

Rachel. 2015. Trans*formative experiences. Res

Philosophica 92: 419–40.

Mihailov, Emilian, and Alexandru Dragomir. 2018. Will

cognitive enhancement create post-persons? The use(lessness) of

induction in determining the likelihood of moral status enhancement. Bioethics 32: 308–313.

Paul, L. A.

2014. Transformative experience.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Paul, L. A. 2015a. Transformative choice: Discussion

and replies. Res Philosophica 92: 473–545

.

Paul, L. A. 2015b. Transformative experience: Replies

to Pettigrew, Barnes and Campbell. Philosophy

and Phenomenological Research 91: 794–813.

Paul, L. A. 2015c. What you can’t expect when you’re

expecting. Res Philosophica 92: 149–70.

Persson, Ingmar, and Julian Savulescu. 2013. Getting

moral enhancement right: The desirability of moral bioenhancement. Bioethics 27: 124–31.

Pettigrew, Richard. 2015. Transformative experience

and decision theory.

Philosophy and

Phenomenological Research 91: 766–74.

Sample, Ian. 2006. Man rejects first penis implant. The Guardian. September 18.

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2006/sep/18/medicineandhealth.china

(accessed May 18, 2018).

Sandel, Michael J. 2009. The case against perfection. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Savage,

Leonard J. 1972. The foundations of

statistics. Second ed. New York: Dover.

Skyrms,

Brian. 1990. The dynamics of rational

deliberation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University

Press.

Stix, Madeleine. 2016. World’s first cyborg wants to

hack your body. CNN. January 7.

https://www.cnn.com/2014/09/02/tech/innovation/cyborg-neil-harbisson-implant-antenna/index.html (accessed May 9, 2019).

Stoll Benney, Kristen, and Linda A. Henkel. 2006. The

role of free choice in memory for past decisions. Memory 14: 1001–1011.

Stoye, Jörg.

2011. Statistical decisions under ambiguity. Theory and Decision 70: 129–48.

Torres, Phil. 2016. Agential risks: A comprehensive

introduction. Journal of Evolution and

Technology 26(2): 31–47.

Wald,

Abraham. 1950. Statistical decision

functions. New York: Wiley.

Walsh, Emma, and Peter Ayton. 2009. My imagination versus your

feelings: Can personal affective forecasts be improved by knowing other

peoples’ emotions? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied

15: 351–60.

Weirich, Paul. 2004. Realistic decision theory: Rules for nonideal agents in nonideal

circumstances: New York: Oxford University Press.

White, Amy. 2014. Body integrity identity disorder

beyond amputation: Consent and liberty. HEC

Forum 26: 225–36.

Whitmore, G. A., and M. C. Findlay. 1978.

Introduction. In Stochastic dominance: An

approach to decision-making under risk, eds G.A. Whitmore and M.C. Findlay,

1–36. N.p.: D.C. Heath.

Wilson, Timothy D., and Daniel T. Gilbert. 2005.

Affective forecasting: Knowing what to want. Current Directions in Psychological Science 14: 131–34.