Negative Data from the

Psychological Frontline

John Schloendorn

Zauberkugel@yahoo.com

Journal of Evolution and Technology

-

Vol. 14 - April 2005

http://jetpress.org/volume14/schloendorn.html

PDF Version

PDF Version

ABSTRACT

A recent study designed to

investigate a possible psychological mechanism behind the widespread

indifference or opposition towards immortalism is presented. In the

wider context of a psychological experiment, which is not reported

in detail here, the study tested different ways to advertise

immortalism, but failed to identify a superior strategy. The theory

behind the study, possible explanations for the results and

directions for future research are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

“Why are there so few

transhumanists?“, probably every transhumanist asked her- or himself

at some point. Things would be easier if there were more

transhumanists, wouldn’t they? For the pragmatic, the question then

becomes “How can we make more people interested in transhumanism?”,

i.e. a marketing question.

Here, I report on my recent

investigation into these questions, and especially their

sub-questions “Why are so few people committed to greatly increase

the human healthy life span?” and “how can we change that?”. This

important field of transhumanism should strongly benefit from more

supporters, and especially from rich supporters. There does not seem

to be a lack of ideas, how mammalian aging might be reversed, but

rather a lack of people willing to develop these ideas or fund their

development. A prime contemporary example for this is the multitude

of ideas developed by rejuvenation research pioneer Aubrey de Grey

and his desperate calls for people to personally and financially

support his work.[1]

The commitment to augment our

healthy life spans indefinitely using biomedical means (hence

‘immortalism’) is so straightforward and obvious for me, that I have

always been particularly baffled by the observation that it is

shared by very close to zero other persons. Our mythology is

brimming with stories of indefinite youth, such as in the world

religions that promise an afterlife free from physical suffering, or

on occasion even in the modern science fiction literature[2].

But barely anyone seems to deem these scenarios desirable enough to

actually work to bring them about, in the here and now. Enormous

research budgets are used to analyze, catalogue and even attempt to

treat individual degenerative diseases, but only a minute fraction

of the efforts are thrown at attempts to actually reverse the

underlying cause, which is the aging process itself.[3]

Thus, I naturally suspected that a

distinct psychological mechanism might be at work here. I believe it

was first hypothesized by Mike Perry, somewhere in the depths of his

vast book (Perry, 2000), that psychological mechanisms that normally

serve to manage the fear of death might go awry when humans are

confronted with the prospect to live forever and preclude the

formation of the commitment to do so.

This sparked my interest in terror

management theory (TMT). TMT is a well established experimental

psychological paradigm, which holds that humans experience a clash

between our inbuilt fear of death, and our unique ability to foresee

that death is ultimately inescapable. (Solomon et al. 2000) It seems

reasonable to expect that evolution fitted us with a psychological

mechanism to manage the permanent existential terror that might

result from this insight. According to TMT, this is accomplished by

our cultural world views. When we perceive ourselves as a valuable

part of a meaningful and lasting cultural world, we may obtain

self-esteem that is capable to outshine our existential fears and

thereby drive our attention away from our personal impermanence.

Elsewhere, I discussed evolutionary aspects of TMT in more detail. (Schloendorn,

2003)

Various predictions of TMT have been

testified in a considerable number of experiments. (Greenberg et al.

1997) Anxiety-buffer studies demonstrate that threats to self-esteem

engender anxiety (Greenberg et al. 1986), anxiety motivates the

defense of self-esteem (Gollwitzer et al. 1982) and that such

defense can alleviate anxiety (Mehlman and Snyder, 1987).

Mortality-salience studies, on the other hand, demonstrate that

reminders of mortality lead test subjects to bolster their

culturally established world views. Mortality salience has been

demonstrated to increase positive evaluations of those who affirm

one’s own cultural world view and negative evaluations of those who

threaten it (Rosenblatt et al. 1989), ingroup bias (Harmon-Jones et

al. 1996), percieved consensus for one’s own beliefs (Pyszczynski et

al. 1996), reluctance to violate cultural norms (Greenberg et al.

1995), and aggression towards those who violate one’s cultural world

view (McGregor et al. 1998).

This led me to suggest a mechanism

by which terror management might compromise the advertisement of

immortalism. (Schloendorn, 2003, chapter 4) If exposure to the

prospect of physical immortality can trigger increased awareness of

our current mortality and a terror management response, then three

things might happen:

Anxiety buffer effects might

suppress the perception of mortality as a problem and thereby reduce

the need to find a solution. Mortality salience effects might reduce

the disposition to embrace new cultural concepts, such as

immortalism or transhumanism. Mortality salience effects might

discredit the transgressor of cultural norms that a transhumanist or

immortalist necessarily is.

According to this mechanism,

valuable cognitive resources would go their various ways to suppress

and deny the problem of death, thereby ironically adding to the

problem, rather than solving it. Accordingly, I called this new

offshoot theory ‘Terror Mismanagement Theory’ (TMMT). (Though

recognizing that at present it has the status of a hypothesis at

most.)

The internet-based experiment I

report here was designed to empirically assess the validity TMMT.

Although no answer could be obtained regarding this question (See

results section), other results were obtained that may be of some

interest to transhumanist advertisers. These results came from a

section of the experiment, in which participants were presented

different primer questions, designed to modulate their set of

accessible thoughts, and then asked to evaluate immortalism. If one

primer preceded on the average higher ratings of immortalism, then

this could indicate a good general strategy to advertise immortalism

on the internet.

METHOD

Participants.

The questionnaire was listed at ‘The Social Psychology Network’ (www.socialpsychology.org)

and ‘The Web Experiment List’ (http://genpsylab-wexlist.unizh.ch)

under the deliberately vague title “Personality Variables and

Interpersonal Attitudes.” These organizations maintain lists of

web-based psychological experiments and attract participants for the

experiments listed as a free service to fellow internet

psychologists. Most participants were undergraduate psychology

students and most psychology students are female. Such a participant

composition is common in experimental psychology in general, and in

terror management theory in particular[4].

The experiment was not advertised in any other way. During the

runtime of the experiment of about six months, a total of 225

participants submitted results.

Procedure.

Following the guidelines given by

the Social Psychology Network[5],

Participants were asked for their informed consent. They were also

asked to complete all questions in one sequential run, and to

complete them only once. Only questionnaires with all questions

completed were collected for analysis.

After providing basic demographic

information, participants were presented Rosenberg’s (1965)

self-esteem scales. This is a set of 10 questions designed to

measure dispositional self-esteem as a covariate to increase the

sensitivity of the terror management experiment (Harmon-Jones et. al

1997) and to obtain information on a possible relationship between

self-esteem and immortalism.

At this point, participants were

randomly divided into three groups. Each group was presented a

distinct set of primer questions. The answers given to the primers

were not analysed. They were designed only to influence the

participants’ set of accessible thoughts before they would evaluate

immortalism. Primers were either death, positivity, or no primer.

The primers consisted of the

following questions:

Death:

-

Much scientific

evidence suggests that death is a person’s permanent and unequivocal

end. Do you think this is true? Please give reasons briefly.

-

Please describe your

closest encounter with death.

-

Most people are scared

by the thought of their own non-existence. Why do you think that is

so?

Positivism:

The positivism primer was divided in

several sub-classes that could eventually be measured distinctly

from each other. However, I did not yet have the resources to do

this. Only their combined effect was measured. Questions from all

sub-classes were presented in a fixed random order.

Life:

-

Which single

circumstance makes the greatest contribution to your overall

happiness?

-

What of all possible

activities are you enjoying most?

-

What are your most

important plans, or dreams, for the future?

Self-esteem:

-

Which particular

aspect of your character do you value most, and why?

-

What was the greatest

achievement in your life?

-

Who is the person that

you think you are most important to?

Open-mindedness:

-

What was the most

rewarding learning experience for you?

-

Was there any

particular moment when decided to overthrow your established world

view? If so, please give details.

-

What was the most

spontaneous project you undertook in your life?

Science:

-

What do you think was

the greatest scientific discovery of all time?

-

Which scientific

discoveries do you think contributed most to human quality of life?

-

What do you think will

be the most important scientific achievement in this century?

Participants were randomly assigned

to a priming condition upon enrollment in the survey. After deleting

one participant’s responses, because (s)he had not entered

meaningful data, 95 participants remained in the ‘no primer’ group,

60 in the ‘positivism’ group and 69 in the ‘death’ group.

After being primed, participants

went on to evaluate immortalism. They were given the cover-story of

an experimental personality assessment test, which involved

fictitious role playing. Participants were asked to adopt the role

of a wealthy person, willing to make a contribution to a good cause,

and then presented an adapted version of the Immortality Institute’s

sample funding request letter.[6]

In this letter, a hypothetical Immortality Institute member briefly

describes the goals and means of immortalism and then asks the

reader for financial support.

Participants were then asked to rate

of five point scales:

-

How much they agreed

with the goals described in the letter.

-

How likely they would

support the author.

-

How much money, if

any, they would donate.

A composite measure was calculated

by addition, which is hence referred as ‘i-score’.

The questionnaire went on with a few

additional questions that I will not detail here.[7]

Most were either cover questions or terror-management questions,

which obtained no results. The primary result, with which this essay

is concerned had by now been collected.

Some of the terror management work

was incorporated in distinct studies. The key terror management

questions to be addressed by all studies together were:

1.) Are immortalists

terror-management deficient?

2.) Can mortality salience adversely

affect subjects’ evaluation of immortalism?

3.) Can immortality salience trigger

a similar effect as mortality salience?

4.) If the answer to 2.) and 3.) is

yes, can the effect be compensated or overcompensated by appropriate

priming?

RESULTS

The attempt to replicate a standard

terror management experiment from the literature as a positive

control failed. Although the questionnaire was replicated nearly to

the letter as well as in certain variations, the number of

participants was considerable and means were distinct, intrinsic

variance within groups remained too high to make the result

significant.[8]

It may be that the internet is not sensitive enough to conduct this

type of experiment. This idea is to some degree supported by the

fact that despite intensive efforts, I have not found any reports of

internet-based terror management experiments. All successful terror

management work reported in the literature that I am aware of was

conducted either in laboratory settings or in defined public places

(Pyszczynski

1996).

In conclusion, it was not possible

to obtain results that could be interpreted to answer the terror

management related questions.

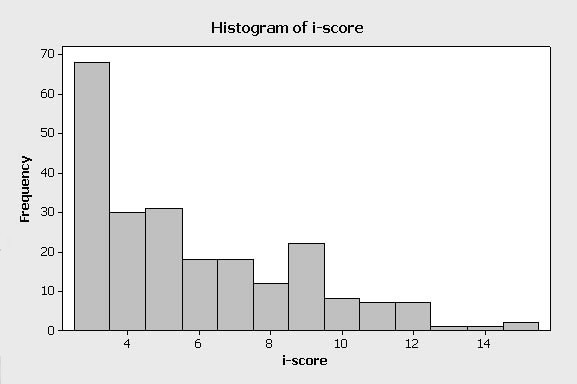

The assessment of the death- and

positivism primers on the advertisement of immortalism did yield

interpretable results. The frequency distribution of combined

immortality score (i-score) roughly followed an exponential decay

with slight extremism added at both ends. Minimal i-score was by far

the most frequent choice. (Figure1) Each of the three sub-measures

(agreement with the goals, likelihood of support and magnitude of

financial donation) showed similar distributions.

Figure1: Frequency

distribution of combined immortality score (i-score)

among all test subjects.

One-way ANOVA revealed that the

primer condition (no primer vs. positivism primer vs. death primer)

had no significant effect on i-score (p>0.3). Each of the three

sub-measures (agreement with the goals, likelihood of support and

magnitude of financial donation) behaved similarly vs. primer (all

p>0.2) and correlated strongly with the other two sub-measures. (all

ANOVA p<0.0001).

To explain some of the variance in

the ANOVA, a general linear model (GLM) was calculated using

Rosenberg’s self esteem scales, age and gender as additional

factors. In this model, the primer condition still had no

significant effect on i-score (p>0.6) or its sub-measures.

Self-esteem and age also had no significant effect. (p>0.9 and

p>0.5, respectively) Gender did have a significant effect (p<0.02),

indicating that males (mean i-score: 6.33) are more supportive of

immortalism than females (mean 5.67).

DISCUSSION

The transhumanist readership

probably knows from their own experience that most people exhibit no

or nearly no immortalism at all. This is well reflected by the i-score

frequency distribution (Figure1). It is equally well known that

immortalists are mostly males. Similar results have been reported in

a survey relating to cryonics. (Badger, 1998) The raw findings of

this survey are thus as expected, which provides some validation for

the method used.

It could be argued that the

complicated decision process towards making a charitable donation

can potentially introduce many variables that make the advertisement

success hard to measure. (Bendapudi et al. 1996) However, in the

end, it must be the goal of immortalist advertisement to make its

target contribute to immortalism, i.e. initiate and complete a

decision process similar to that of charitable donation. But it

could be counted as a preliminary success if only an early stage of

that process could be induced. This is why the three measures were

assessed separately. It was found that neither general agreement,

nor the likelihood for any kind of support, nor a specific financial

contribution could be elicited by the primer questions. This, and

the observation that the three sub-measures correlated strongly with

each other, is consistent with the idea that similarity of values

with the beneficiary can result in greater charitable contributions.

(Bendapudi et al. 1996, 42)

Another potential objection to the

method derives from the fact that the web-based setting used turned

out to be inappropriate for the terror management part of the

experiment. Thus it must be asked whether it is then appropriate for

the immortalist advertisement part. I suggest that it is, because a

large fraction of immortalist and transhumanist advertisement is

actually taking place on internet pages. Therefore, these equally

internet-based findings are directly relevant to transhumanists’

preferred form of advertisement.

One positive finding in this study

(confirming at least one other, Badger 1998) was the effect of

gender on immortalism, raising the question why females show even

less immortalism than males do. It may be helpful to understand this

in the context of existing literature on gender effects on death,

aging and health attitudes.

The effect of gender on death

attitudes is complex. Although females sometimes exhibit more

negative attitudes to death on certain sub-measurements, (DePaola et

al. 2003) the effect seems to be mediated by a whole lot of

intrapersonal variables. These interactions are still subject to

investigation. (Neimeyer et al. 2004) Thus, a clear effect of gender

on immortalism would not be predicted from death attitudes.

But since life-extension would

likely correlate with health extension, and this is mentioned in the

funding request letter used to evaluate immortalism with moderate

emphasis, gender effects on attitudes towards biological aging and

health behaviors could also be instructive. Females’ attitudes

towards aging in different western cultures are quite clearly and

uniformly more negative than males’. (McConatha et al, 2003) This

can be in part explained by the discrepancy between the

physiological changes of aging and the cultural ideal of female

youthful appearance. (Higgins, 1987) Immortalism could help women to

meet this ideal in the future, and thus increased immortalism would

be predicted form female aging attitudes.

Perhaps as a consequence of their

aging attitudes, females tend to be more proactive in their health

behaviors than males in different cultures (Ray-Mayumder, 2001). If

commitment to immortalism is understood as a particularly farsighted

form of proactive health-behavior, this would equally predict

increased immortalism in females.

In sum, the effect of gender on

immortalism is different from, or even antithetic to what would be

predicted from its effects on health attitudes, which are a logical

correlate of immortalism and its effects on aging and death

attitudes, which are its logical antagonists. Possible explanations

include the idea that as far as immortalism is concerned, people

simply are not logical, perhaps owing to excessive psychological

coping with and suppression of the problem that aging poses for

personal well-being. For example, the acceptance of aging as

inevitable and normal can correlate with the ability to maintain a

positive sense of self. (McConatha et al. 2003, 205) This is

compatible with females’ more concerned aging and health attitudes,

which may prompt more excessive irrational coping in the face of the

inevitability of aging. An additional part of the problem may be

inadequate communication of the idea that human life extension would

likely correlate with healthy life extension. If participants

suspected that real anti-aging medicine would bring them only a

prolonged period of physical frailty, then the findings would be

equally explicable. This almost cries for further investigation.

Gender effects might end up being a useful thread through the swamp

of immortalist marketing research.

It has long been debated among

immortalists, whether it is better to start advertising with the

badness of death, or the goodness of life. According to these

findings, at least for internet-based advertisement, it does not

matter.

Like others who spent considerable

time studying this issue[9],

I have not heard of anyone ever being persuaded that life extension,

or in fact life in general, is desirable. The findings of the

present study provide support for this more or less intuitive idea.

The priming of obvious points for immortalism, namely the goodness

of life and the badness of death had no effect on subjects’ the

measure of immortalism used.

It may be that a given person’s

disposition towards immortalism reflects characteristics of her

personality that are so fundamental as to be inaccessible to the

direct and brief advertisement strategy employed in this study.

As long as an effective general form

of advertisement cannot be found, one might feel tempted to abandon

the course of persuasion of arbitrary persons to embrace

transhumanism. Rather, advertisement could focus on targeting those

already predisposed to transhumanism and inform them of the

possibility that their goals may not be as unrealistic as they

think. The identification of suitable target groups is of foremost

importance here. Both short surveys of the transhumanist community

and simple ‘similar interests’ - search engines on the internet

could be valuable tools to do this. You may not be surprised that I

currently have work in this direction underway. Preliminary results,

for example, indicate a substantial bias of immortalist community

members towards people with a background in computer science.[10]

Perhaps, meaningful terror

management experiments should be initiated in an appropriate

laboratory setting. If any reader has access to suitable

infrastructure, I would be happy to hear from you.

Furthermore, disagreement with the

goals of immortalism is likely an important factor limiting the

numbers of active immortalists. This is supported by the tight

correlation of the two forms of support for immortalism measured

with the agreement with its goals. Thus, it might be worthwhile to

look into other mechanisms that may drive this disagreement. I will

give a brief overview of three possible such mechanisms.

One mechanism would be the view of

one’s own life as a closed concept with a defined end. Though

unfamiliar to the transhumanist, it is possible to view one’s life

as a project that is inherently limited. For example, one can

believe that life’s purpose is exhausted after accomplishing what

persons born in a similar cultural context normally accomplish. When

one’s cultural context is a sufficiently strong component of one’s

personality, there is indeed no way one could personally continue a

meaningful existence after that cultural context has become

exhausted. (Williams, 1973) Another example might be the desire to

rear children, make sure they have a good start, and then remove

oneself, so that they may fully unfold their potential. Such bounded

views of one’s life concept are by no means better or worse than the

transhumanist open-ended view. It may be a matter of nature, nurture

or active personal choice. Inherently bounded personalities have

little rational requirement to live longer than they need to fathom

these bounds. Such views may lie at the root of the familiar boredom

argument, and have been amply debated in the context of physical

immortality in the theoretic literature (Glannon 2002, Harris 2002a,

Harris 2002b), but I know of no attempts to empirically validate the

idea, let alone put it to a use in immortalist advertisement.

Furthermore, memetics pioneer

Blackmore argued that the adoption of a set of culturally accepted

memes can enhance the genetic sexual attraction of the meme carrier.

(Blackmore, 1999, 78) Therefore genes should be selected that

dispose their carriers to adopt preferably memes which are

culturally accepted. This was proposed as a mechanism driving

cultural runaway selection, accounting for the extreme sexual

attraction that successful movie stars or rock musicians enjoy.

(Miller, 1998) From this point of view, transhumanism could be bound

by the same negative feedback mechanisms that keep any small

subculture, new political movement or religious sect small. Such

movements are eyed with suspicion, simply because they are small and

exotic. It may thus be beneficial to explore the memetic mechanisms

that allowed some small cultural movements, rather than others, to

break through this doom loop and become prevalent. Utilizing the

cultural acceptance of the ‘science’ meme to advertise transhumanism

may be a way to go.

A third possible mechanism could be

the need to avoid displays of self-interest in a social context. If

one desires physical augmentation in general and immortality in

particular, this equals desiring a huge advantage for oneself. In

human history, huge advantages for one usually accompanied

disadvantages for others, and thus are interpreted as egoism. To

access the benefits of reciprocal altruism, however, only hidden

egoistic motives were allowed, but their open admission was selected

against. (Dawkins, 1989, chapter 10) Thus many people may have

emotional reservations against forming a selfish desire for physical

immortality. Forms of advertisement that avoid the outright desire

for immortality should thus be explored. For example, the term

‘regenerative medicine’ has this potential, because medicine seems

to be mainly about altruistically helping the needy. Physical

immortality as a consequence of perfected regenerative medicine

comes to mind only at closer inspection.

Of course, apart from these rather

sophisticated psychological efforts, more obvious strategies of

advertisement, which are already being employed, could use some

empiric validation. One could, for example, ask whether it increases

advertisement success to emphasize concepts like the biomedical

feasibility of life extension, eternal youth over eternal old age,

personal relevance due to biogerontological “escape velocity” (de

Grey, 2004), etc.

Although most of the data obtained

in this experiment was negative, I hope that I helped to set a trend

towards professional investigation of the ancient transhumanist

advertisement problem. Even though I failed to identify a superior

general advertisement strategy, I strongly encourage others to

attempt the same. Ardent support among the broad population is the

most promising means to actualize many transhumanist dreams and make

this world a much better place. Although the prospects of obtaining

such support may seem slim at this time, the huge potential benefit

warrants in-depth exploration of every such chance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am deeply indebted to Bruce J.

Klein (www.imminst.org)

for hosting the web experiments and extensive technical support.

Special thanks goes also to:

Dr. Eva Jonas (Ludwig Maximilian

University, Munich, Germany) for advice on terror management theory

and sharing the details of her experimental design.

‘Dave’ from the ImmInst forums for

helpful comments.

Silke Huffziger for help with the

statistical analysis and sharing her view on the highly

controversial subject of immortalism.

An anonymous reviewer whose comments

helped to clear some important conceptual points, thereby

substantially improving the manuscript.

FOOTNOTES

[2]

For example, refer to the fascinating works of Robert A.

Heinlein

[3]

For example, reversing aging or life-extension are not even

considered in the mission statements of either the National

Institute of Health

www.nih.gov/about/almanac or the National Institute of

Aging

www.nia.nih.gov/aboutnia as means to increase human

health, while they do encourage the treatment of individual

diseases, in order to promote the what they call “healthy

aging“.

[4]

See nearly any terror management experiment cited in this

essay.

[7]

unpublished data. 2004.

[8]

unpublished data. 2004.

[10]

This idea is originally from de Grey A (2004), personal

communication.

REFERENCES

Bendapudi N, Sing SN and Bendapudi V. 1996 Enhancing

Helping Behavior: An Integrative Framework for Promotion

Planning. Journal of Marketing 60(3): 33-49; p. 42

Blackmore, S 1999. The Meme

Machine Oxford University Press, p. 78.

Dawkins R 1989. The Selfish

Gene Oxford University Press, see especially chapter 10.

De Grey ADNJ 2004 Escape

velocity: why the prospect of extreme human life extension

matters now. PLoS Biology 2(6): 723-26 Freely

available at

http://www.gen.cam.ac.uk/sens/CwM.pdf

DePaola SJ, Griffin M, Young JR, Neimeyer R 2003 Death

anxiety and attitudes toward the elderly among older adults:

the role of gender and ethnicity. Death Studies 27:

335-54

Glannon W 2002. Identity,

Prudential Concern, and Extended Lives. Bioethics

16(3): 267-283.

Gollwitzer PM, Earle WB and

Stephan WG 1982. Affect as a determinant of egotism:

Residual excitation and performance attributions. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 43: 702-709.

Greenberg J, Solomon S and

Pyszczynski T 1997. Terror management theory of self-esteem

and cultural worldviews: Empirical assessments and

conceptual refinements. Advances in experimental social

psychology, 29: 61-139.

Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T

and Solomon S 1986. The causes and consequences of the need

for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In RF

Baumeister (Ed.) Public self and private self (pp. 189-212)

New York: Springer-Verlag.

Harmon-Jones E et.al. 1997. Terror Management Theory and

Self-Esteem: Evidence That Increased Self-Esteem Reduces

Mortality Salience Effects Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology 72(1): 24-36.

Harris J 2002a. A Response

to Walter Glannon. Bioethics16(3): 284-291.

Harris J 2002b. Intimations

of Immortality - The Ethics and Justice of Life Extending

Therapies. Current Legal Problems 55: 65-95.

Higgins ET 1987. Self-discrepancy: A theory relationg self

and affect. Psychological review 94: 319-40.

McConatha JT, Schnell F,

Volkwein K, Riley L, Leach E 2003 Attitudes towards aging: a

comparative analysis of young adults from the United States

and Germany. International Journal of Aging and Human

Development 57(3): 203-15

Mehlman RC and Snyder CR

1985. Excuse theory: A test of the self-protective role of

attributions. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 49, 994-1001.

See also Miller, G. F. 1998.

How mate choice shaped human nature: A review of sexual

selection and human evolution. In C. Crawford & D. Krebs

(Eds.), Handbook of evolutionary psychology: Ideas,

issues, and applications 87-130. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Neimeyer RA, Wittkowski J, Moser RP 2004 Psychological

research on death attitudes: an overview and evaluation.

Death Studies 28: 309-40.

Perry M. 2000. Forever for

All. Universal Publishers, FL.

Ray-Mazumder S 2001. Role of gender, insurance status and

culture in attitudes and health behavior in a US chinese

student. Ethnicity and Health 6(3-4): 197-209

Rosenberg M 1965. Society

and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, New Jersey:

Princeton University Press.

Rosenblatt A, Greenberg J,

Solomon S, Pyszczynski T et al. 1989. Evidence for terror

management theory: I. The effects of mortality salience on

reactions to those who violate or uphold cultural values.

Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 57: 681-690.

Schloendorn J 2003.

Evolution and its implications for aging, death and the

extension of the human life span. The World Transhumanist

Association, Haldane Paper 2003. Freely available at

http://www.transhumanism.org/tv/Haldane2003.htm

Solomon S, Greenberg J and

Pyszczynski T. 2000. Pride and prejudice: Fear of death and

social behavior. Current Directions in Psychological

Science 9(6): 200-204.

Williams B 1973. The Makropulos Case: Reflections on the

Tedium of Immortality. In Problems of the Self. Williams,

ed. Cambridge MA, Cambridge University Press: 81-100.

|